There’s a new theme every day on It’s Vintage. Read more articles on today’s topic: Tom Ford at Gucci.

In October 1994, the publicist for Gucci nearly begged journalists to attend Tom Ford’s first women’s show in Milan. Within a year, Ford would be hailed as “the most directional designer in Milan” for his sleek tailoring and retro ‘70s glamour. And Madonna, dressed in a teal-blue satin shirt and hip-huggers at the MTV Music Video Awards, would invite even more attention when she chimed about her outfit, “Gucci, Gucci, Gucci.”

But that autumn it was easy to be skeptical. Despite its golden association with playboys and Hollywood goddesses, and despite success by the company’s creative director, Dawn Mello, who pushed the house to revive its snaffle-bit loafer and bamboo-handle bag, Gucci had failed to achieve its potential — and to distract consumers from designers like Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace, or upstarts like Romeo Gigli. At one point Gucci couldn’t even meet its payroll. Maurizio Gucci, after selling out family shares to Bahrain-based Investcorp, had been ousted. (He later was gunned down in a murder-for-hire arranged by his ex-wife.) Then in the spring of 1994, Mello left, returning to Bergdorf Goodman as president.

Ford, who in his four years at Gucci had been an invisible backroom presence, was now on his own. And the ladylike knits and full skirts in wistful colors and prints that he showed reflected his tentative grasp of the brand’s identity. Speaking by phone last Friday from his home in London, Ford said with a laugh, “It wasn’t a bad show. It just wasn’t anything.” He said that his “brain was still full” of the type of fashion that Maurizio Gucci had wanted — classics that related to Gucci’s scarf history and leather goods. But clearly no one cared. Besides, Gucci didn’t have a ready-to-wear story to tell — not the way, say, that Chanel did. It would have to be invented. But given the brand’s uncertain future, with Investcorp weighing a sale of Gucci, was that even feasible? Depressed, Ford says he was ready to leave after the fall 1994 show.

As it happened, his sense of failure became his wedge. He felt he could do as he pleased because he had nothing to lose. “I had a moment where nobody was looking at anything I did,” he says. Then, too, he has always been the kind of person who knows what he wants. On his first date, in 1986, with Richard Buckley, the writer who became his partner, Ford announced that within ten years he would be a millionaire and designing his own line in Europe. Preparing for his Gucci men’s show, in January of 1995, Ford began questioning how he thought people wanted to look. At the time, Gucci’s archives consisted of a cardboard box filled with glossy press snaps of movies stars like Liz Taylor and Grace Kelly wearing Gucci scarves or walking through an airport with a bag. The glamour of Gucci resided in their celebrity rather than in anything they specifically wore. That’s what Ford tapped into, and he would emphasize that notion in his shows by putting a single spotlight on the models as each came down the runway. Versace often used the same effect, but the difference was that Ford killed the backlight, so that you were actually forced to notice the clothes and the models — and not someone sitting opposite. He also had the sense, he said, that people wanted to look sexy again. Fashion had reached the point where it was all minimal and proper, apart from the romance of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano, whose businesses were still relatively tiny.

So in January, in Florence, Ford sent out velvet hip-huggers and a long, thin, new Gucci loafer in patent leather, a look that some writers related to mod and James Bond. He repeated the idea, more or less, for his women’s show that March. He also ignored a clause in his contract that said he couldn’t take a bow. “I thought, You know what? I’m going to do what I think is right. I’m going to step on the runway,” he recalled.

“What did Gucci executives have to say about that?” I asked him.

“The next day you could not get into the showroom. It was absolute hysteria. So, no, no one gave me flak after that.”

It’s interesting to trace journalists’ reactions between 1994 and March of 1996, when Ford showed perhaps his most celebrated collection, the one with the slinky cutout gowns in white jersey, for which he received a standing ovation. Until the hip-hugger men’s show, Amy Spindler of the New York Times, who became one of his most ardent admirers, typically landed Ford’s men’s shows near the bottom of her reviews. But after Florence she called the show “the most directional for the magazines.” By July, she had upgraded Ford to “the most directional designer in Milan,” and in September of 1995, in an insightful column headlined “Flip-Flop: The Runway Leads the Street,” she elaborated on “the Gucci influence.” Fashion brands at all levels were suddenly turning out hip-huggers.

Those three seasons — the velvet collection, the so-called hippie show with clashing prints in the fall of 1995, and the white-dress show — are what made Tom Ford at Gucci. Revenues in the first nine months of 1995 doubled, to $342 million, over the previous year. At the same time, he began to work with the stylist Carine Roitfeld and the photographer Mario Testino, helping to expand their own domination in the ‘90s and beyond. Ford first made the connection to Roitfeld in 1994, while looking at a shoot she had styled for French Glamour. In so many words, he said, “This is my woman.” In reality, a number of women have served as Ford’s muses, notably Lisa Eisner in Los Angeles. But Roitfeld’s ultrasexiness, her élan, had a huge impact on him. And very much in the tradition of designers like Bill Blass and Coco Chanel and Yves Saint Laurent, Ford knew that he had to design for an actual woman, and not some cardboard creature.

In so many ways, Ford’s run-up at Gucci is instructive — though, to be sure, the fashion world has now changed beyond recognition. He was one of the very first designers to put into play the notion of mass luxury — that is, stuff that anyone could aspire to and maybe acquire. Despite the incredible glamour of Ford’s shows, which he carried over in the provocative advertising images, the clothes were essentially wearable. Christopher Bailey has taken a similar approach at Burberry; not coincidentally, both Ford and Bailey have a strong business sense. And in abstracting the notion of celebrity from that slim box of Gucci photos, and in spectacularly elevating that notion on his runway, he was foreshadowing the current mania for celebrities and the red carpet. He really defined the conversation for the industry in the second half of the ‘90s.

Chatting with Ford, I remarked that breaking with Gucci’s storied but rather conventional past must have saved him. He laughed. “Yes, but in fashion you never feel that way. Every time you turn your back and walk off the runway you think, Fuck, I got away with that this time. What am I going to do the next time? Literally, I was always terrified.” But in the lull before his velvet hip-hugger show, before Madonna, it did help that no one was looking. As he said, “I could have sent anything down that runway.”

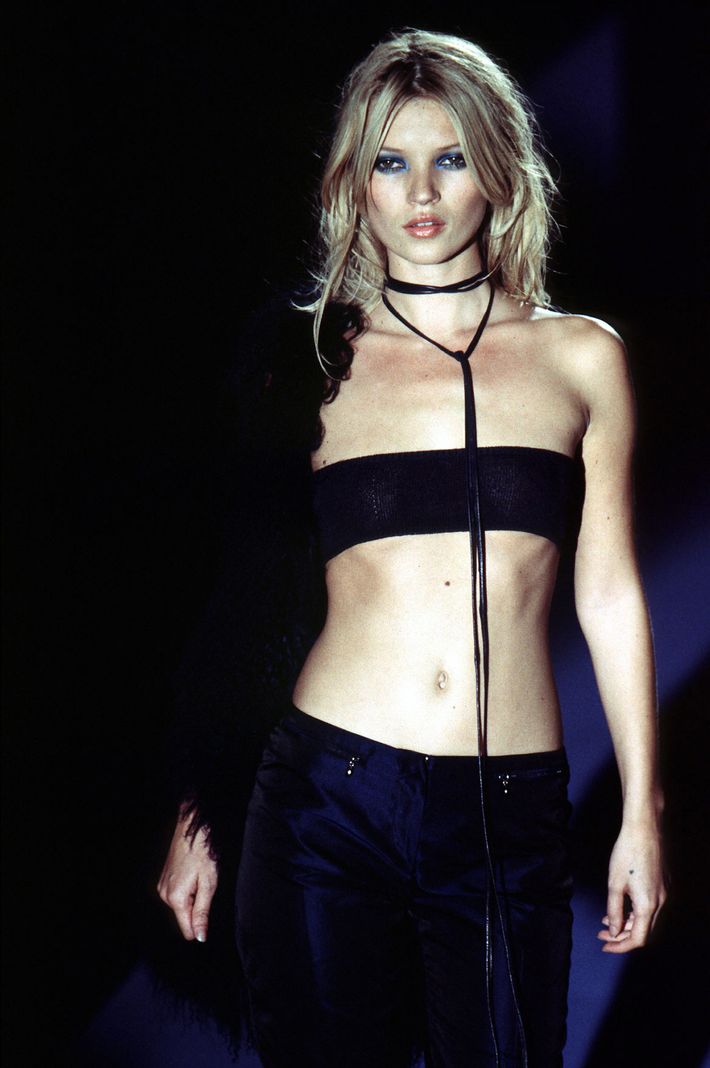

Kate Moss, who would later go on to become the face of the brand in 2001, walks in the spring 1996 Gucci show.

Brightly colored furs were a staple, like this one Stella Tennant wore in the designer’s fall 1997 show.

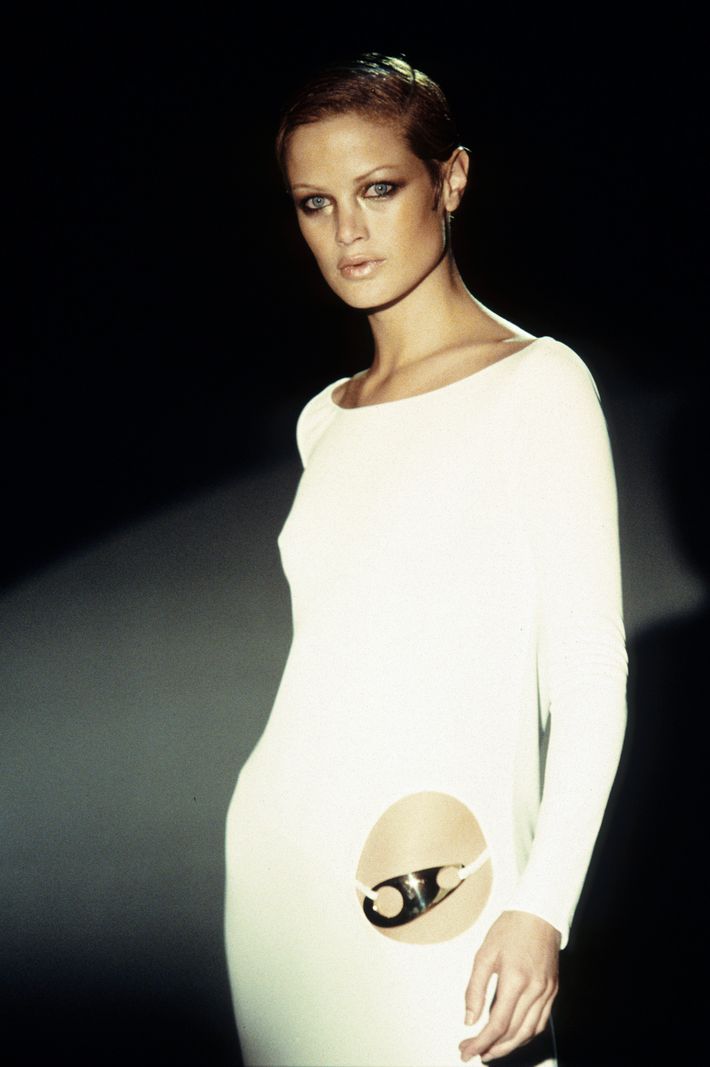

An influential cutout look, on Carolyn Murphy in the fall 1996 show.

Ford loved a deep V. Linda Evangelista worked a ‘70s take on the look for his spring 1996 collection.