You wouldn’t necessarily expect a film about race relations from Gillian Laub, a New York photographer known for family portraiture with a sense of unreality, including a harrowing series of images of Israeli Jews, Israeli Arabs, and Palestinians. But there’s nothing about the way that America deals with race that’s not about both our shared history and what we learn from our families. Laub became involved in the project in 2002, when Spin received a letter from a 19-year-old subscriber, Anna Rich, asking to document an injustice in her hometown of Mount Vernon, Georgia. Because of her local high school’s racially segregated prom and homecoming celebrations, Rich wrote, she was forbidden from taking her black boyfriend as her date. On assignment for the magazine, Laub traveled to the town to visit Rich shortly after — and has been documenting the Mount Vernon community ever since. In 2009, her photographs of the Montgomery County High School’s segregated proms were published in The New York Times Magazine, resulting in national outrage that led the town to finally integrate.

On Monday, HBO will broadcast Southern Rites, Laub’s documentary about the murder of a black boy and the ways in which interracial sex and dating between young Americans remains a locus of taboo and shame even in 2015. (Her 12-year visual study of the town is also the subject of a new book and exhibition at the International Center of Photography.) Laub was rushing through an airport on her way to a premiere of the film at Atlanta’s National Center for Civil and Human Rights when we caught up with her by phone.

Who is going to be at the event in Atlanta?

A lot of people from the town that’s featured in the film, plus Anna Rich, who is the original girl who reached out about the segregated proms in Montgomery County. She wrote a letter to Spin, which was one of the magazines she subscribed to, saying, “Please come to my town, there’s such an injustice going on. I have a black boyfriend and I can’t take him to my prom because they’re segregated.” She was a straight-A student and a cool girl, a very unique person — down with the white girls and black girls.

Is that when you first heard of segregated proms?

Yes. By the time I got down there, Anna had just graduated but her sister Julie, who’s in the film, was in high school. Prom had passed and their next segregated event was homecoming. We went down that homecoming in the fall of 2002, and stayed at the local hotel, the Mount Vernon Inn and Suites. Anna chaperoned us around town, showing us everything.

Where was the prom held?

It’s often in a neighboring town, Vidalia — you know, where we get the name of the onion. That’s their big town, and it would be in the Vidalia Community Center. There’s a Hampton Inn there, and I became a regular at the Hampton Inn when I was doing the film. Every time I came in, they were like, “Oh hey, Ms. Gillian, hey, Ms. Gillian.”

What did you think of the scene down there at first?

It was completely surreal because I was in this idyllic, gorgeous southern town with all these kids cheering. And in the suburbs, prom and homecoming is the biggest thing. There was a parade with all these floats, and in some ways it seemed like a more integrated community than I’ve ever seen. And then on the other hand, there’s a homecoming ballot with a column for a white girl and then a column for a black girl. And then on the float, there’s two girls — a white girl and a black girl — and then later on in homecoming court, everyone is separated by race. They even have the kindergartners separated by race, handing the crown to the black queen, and then a white little kindergartner, handing the crown to the white queen.

So what is segregated prom about? Is it about segregating a community, or about policing interracial dating?

It’s about interracial dating. Interestingly, when I interviewed one of the first crossover teachers at the school, she explained that the tradition actually started in a democratic way, because when the schools integrated in the early ‘70s, they didn’t want the queen to always be white. They had two on the principle of separate but equal, and both would win.

So there was a justification.

There was. Tradition. That’s the word that everyone says down there. It’s all about tradition.

What was the reaction when you published photographs of the homecoming in Spin?

I heard that parents were driving to Atlanta to buy all the copies off of the stands so no one would see it. In 2008, I called up the school on a whim, because I had really been haunted about what I had seen down there when I was on assignment, and Anna and Julie had moved away. Obama was president, so I thought, They can’t still be having segregated prom, there’s no way. I said to the school, “Hey, I’m just wondering when your prom was?” and they said, “Which one?” So I was like, “Huh.”

You returned to shoot the proms for The New York Times Magazine, and what happened then?

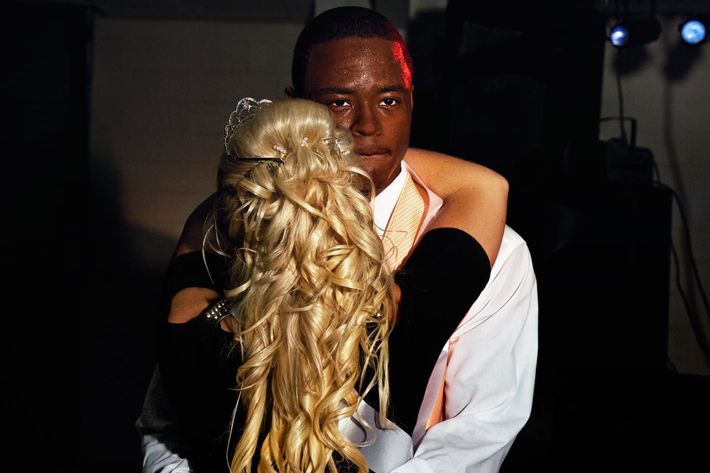

Since I got there just a couple days before the white prom I didn’t have much time to meet people and do research. I met Keyke right away, this beautiful girl who was in a parking lot jumping up and down, and I asked, “What’s going on? Tell me why you are so excited?” And she said, “I’m going to be the first black girl to go to the white-folks prom!” And I begged, “Please let me follow you!” She asked her parents’ permission and they said yes. But later the next evening I got a hysterical phone call that she had been disinvited because the boy’s parents weren’t happy about him taking a black girl, so she said, “Please come back down and photograph me in a couple weeks for my [black] prom,” and I said, “Absolutely.”

So was it smooth sailing from there?

No, not really. The next day I met Harley Boone, who was on the white-prom committee for 2008, and she said I could follow her, but she didn’t want to talk about race. So I said, “Okay, I’m just going to photograph you.” But when I was following her that day getting ready at the nail and hair salon, and then the local photo studio in town, a mother recognized me from the 2002 Spin shoot and lost her mind. And I said to her, “I’m not photographing your child, I’m following Harley,” and she just kept screaming, “Go back to where you came from, leave us alone.” Next thing I know, I was at a Ruby Tuesdays with the kids and two cops are coming up to my table. They said, “You better go back to where you came from, people here — we won’t be able to protect you. People here will take the law into their own hands.”

Oh my God, okay.

It was totally frightening. I said, “Are you threatening me?” And they said, “We’re warning you.”

So when you began the film, you were aware that your presence was not desired in the town.

I was very aware that people didn’t want me there. Some trips I thought, Oh, this is actually okay, and other trips were super-scary. I was there a lot when I was pregnant, and that’s when I was most scared. I was attacked by the sheriff before I was pregnant, filming and photographing the homecoming parade. Time had passed and I was trying to show how things were changing. I was photographing a public parade and he attacked me. I was also pulled over a lot, with dogs sniffing my car, and my biggest fear was that they were going to plant something and I would end up in jail and have no recourse.

And when you photographed in Israel and Palestine, were you scared on this level?

That was the craziest thing. I was more scared — I’m not joking — there, than I was in the Middle East. It was so obvious there was something they were trying to hide, something that was shameful, and the [anger] was directed toward me. In Israel, nothing was directed toward me. It had nothing to do with me. It felt very different.

Why do you think you’ve gravitated toward projects about race and ethnicity, after so much photography about families?

I’m definitely attracted to cultural tension. In Israel, I was trying to show the similarities between the supposed enemies and the stories that you don’t see in the headlines. In Israeli, at first, people said, “This is what we deal with every day. Do we need to see these photographs? This is an outsider coming in.” But then there was a positive response, of Israelis looking at the image and looking at people as human beings, not as enemies. But in general, I always just try to dig deeper into issues that I want to understand more, really. And get to know the people that are part of them.