Tonight’s two Republicans debates — the first featuring non-top-ten candidates; the later, more important one featuring the ten candidates currently leading in the polls — are likely to be memorable for a number of reasons: As in any Republican primary debate, there will be attempts to appeal to the party’s base that will come off, in retrospect, as sounding a bit crazy. Plus, with so many candidates — including one named Donald Trump! — there are likely to be some very enjoyable interactions.

The debates will be solid political entertainment no matter what, but adding just a little bit of social science to the mix can help reveal hidden aspects and important moments that might otherwise slip by unnoticed. So here are three simple things you can do to be a more informed debate consumer — not just tonight, but for the rest of the campaign.

1. Understand the basics of how first impressions work.

Back in May, Heidi Grant Halvorson, a Columbia researcher and author of No One Understands You and What to Do About It, spoke with Science of Us about the science of first impressions. As she explained, there’s a reason for clichés like, You only get one chance to make a first impression: Research really has shown that those moments have an outsize impact on how a new friend or co-worker judges you.

Given the obscurity of some of the candidates who will be onstage — and the fact that many Americans don’t usually follow politics all that closely — it’s not a stretch to view tonight as a big first-impression opportunity for many in the GOP field. But other than the obvious observation that it’s better to make a good first impression than a bad one, what exactly should we be on the lookout for?

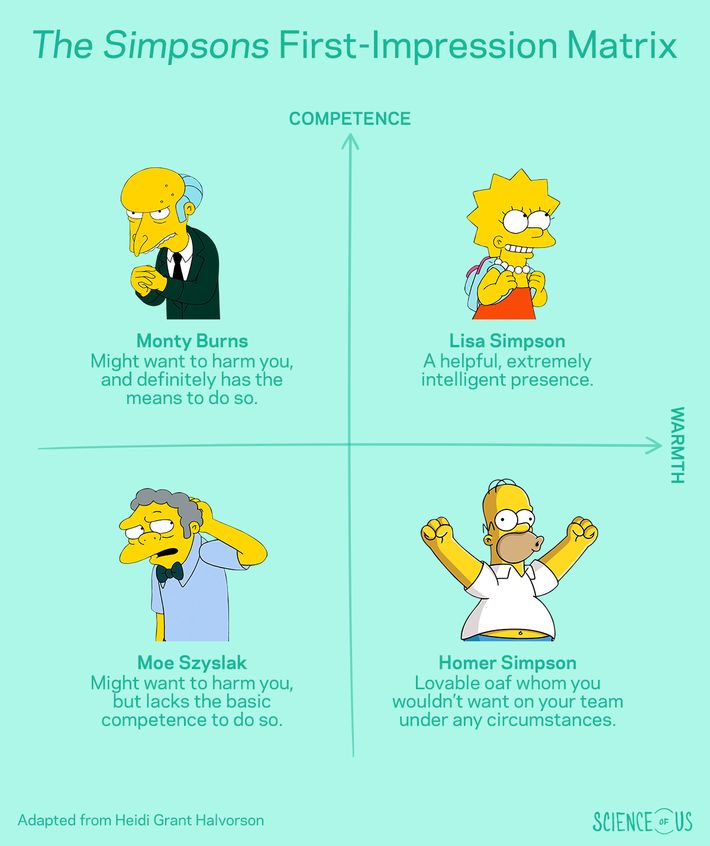

This Simpsons matrix Halvorson shared with us can help:

The basic idea here is that people primarily make their first impressions by assessing two personality dimensions: competence, or their basic ability to get stuff done; and warmth, or the presence or absence of good intentions.

In a political (or business) context, it’s important for the person being judged to be mindful of both. If you score high in warmth but low in competence, you’ll be seen as a friendly but ineffectual individual; if you score high in competence but low in warmth, you’ll be seen as potentially threatening.

Not unlike an interview, the debate format makes all of this very tricky because candidates only have a little bit of time to communicate a lot of information. The prospects for missteps are high; a candidate might rattle off their list of achievements without providing any sense of connection, leading voters to stick them in the icy Mr. Burns quadrant; or they might rattle on about how much they love and want to improve America but fail to provide any indication that they’re actually capable of getting the job done, leading to an unfortunate self-Homerization.

2. Watch for candidates who do — or don’t — mirror the language styles of their conversation partners.

People who study business and political communication think language style matching (LSM), or the extent to which one partner in a conversation mirrors the conversational style of the other, sends important under-the-radar messages about that speaker’s credibility and empathy.

For a recently released study in Personal and Social Psychology Bulletin, a team led by Daniel Romero of the University of Michigan analyzed transcripts of presidential debates between 1976 and 2012 to measure the extent to which candidates mirrored the speaking style not only of their debate opponents, but also of their moderators and question-answers, and what effect this had on their subsequent performance in post-debate polls. (Specifically, the researchers looked at the frequency of usage of certain common words, from commonly used pronouns to quantifiers like all, remaining, and somewhat.)

The team found that higher levels of LSM matching correlated with better performance in the polls. “When a candidate responded to a question or gave a rebuttal that matched linguistic style of the comment before theirs, their comments were more fluent — that is, they became easier to process,” said Columbia University’s Adam Galinsky, a co-author on the study, in an email. “And we know that fluency is a strong predictor of persuasiveness.” (Matching might also display “greater perspective-taking,” he and his colleagues note in the paper.) To the researchers, this finding helped debunk an alternate theory: that people who employed greater degrees of LSM would be seen as followers and therefore unpresidential.

This research suggests that tonight, and in every subsequent debate, many subtle aspects of the participants’ speech could have an impact on viewers — even if they don’t realize it.

3. Keep an eye on who tries to get noticed, and how.

For the lesser-known candidates, it will be key not to get lost in the din of the large debate format. While Jeb Bush and Donald Trump are already household names, hopefuls like John Kasich definitely aren’t — and this might be their only real chance to jump fully into the spotlight.

Maurice Schweitzer, an organizational psychologist at the Wharton School of Business and the co-author, with Galinsky, of the upcoming book Friend and Foe: When to Cooperate, When to Compete, and How to Succeed at Both, said that that’s one reason to expect some, well, memorable comments tonight. “When you have ten candidates you’re trying to stand out from the crowd, and there’s so much noise, it’s pushing people to become extreme,” Schweitzer explained. Given that subsequent coverage of the debate is only to focus almost exclusively on big, spectacular moments, now is not the time for candidates, particularly lesser-known ones, to reflect pensively on the complexities and nuances of difficult subjects like immigration policy; no, now is the time to call for a giant, state-of-the-art fence, or deportation of all of the nation’s millions of undocumented immigrants, or whatever other big, unrealistic-in-real-life policy proposal will get them the most attention. “You want to be just this side of crazy,” said Schweitzer.

But getting noticed in a crowded field isn’t just a matter of what you say, it’s also about when you say it. “We know that in a long list there’s a recency effect,” said Schweitzer, “so it’s better to go last. There’s some effect for going early, for being first, but the best, the most memorable [spot] is to go last.” So if you witness candidates fighting fiercely for the last word, that’s probably why.

That said, it’s likely that not everyone will take place in these instances of verbal jockeying, or of out-memorable-izing each other, said Schweitzer. He explained that the strategy for the debate’s known quantities are likely to be very different. If you’re, say, Jeb Bush or Scott Walker, you know that you’ll at the very least be in the race for awhile, and that a sizable chunk of the country already knows who you are. There’s less premium to force big moments that will get you attention, because at the moment your goal isn’t to get attention but rather to “look presidential.” Therefore, said Schweitzer, “Bush looks best, Walker looks best staying above the fray.” If they can resist, that is.