One of the most racially diverse U.S. cities, New York is also among the most starkly segregated. As a booming housing market spurs rapid gentrification, with white professionals often staking a wide claim within traditionally black and Latino New York City neighborhoods, how will these new arrivals affect neighborhood dynamics?

New research by Dr. Joscha Legewie, a sociologist at New York University, and Dr. Merlin Schaeffer of the University of Cologne, highlights an interesting aspect of the “fuzzy,” ill-defined boundaries between neighborhoods with vastly different racial makeups: These areas, claim the researchers, tend to have more conflicts between neighbors, even when you control for a host of other factors.

New York has many of these fuzzy boundaries. Perhaps the most historically notable is located on the east end of a white enclave in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights South — the site of infamous 1991 riots involving unrest between Jews and African-Americans that ultimately helped bring down the Dinkins administration. (Legewie hopes that future research into the fuzzy-boundary theory will expand to look at religious and socio-economic differences.) There, over the course of a couple of crosstown blocks heading eastward, the neighborhood shifts gradually from one that’s mostly white into another that’s more than 70 percent black; whereas on the west side of the enclave the black-white divide is sharply defined by a single street. Manhattan has the notorious East 96th Street color line: Below, the Upper East Side is vastly white and the city’s richest neighborhood, while above the divide the average income plummets and the area is almost all Latino and black. Also, if you travel uptown on Broadway along the west side of the Columbia campus until you’re just above 125th Street, you’ll see the proportion of white people drop from two-thirds, to about 40 percent, and, once into Harlem, to just 3 percent.

Legewie and Schaeffer combed through local 311 records for complaints about noisy neighbors, blocked driveways, public drinking, and illegal use of apartments (as Airbnb rentals, for instance). Then they cross-referenced this trove of data with information about the city’s racial composition from the 2010 Census. They also took boundary-detecting algorithms that are typically used to identify, say, the outline of someone’s head in image processing or objects that self-driving cars should avoid, and used them to detect the zones in New York City in which there are gradual racial demographic shifts between two contrasting neighborhoods. (Legewie is set to present his research on August 22 at a conference of the American Sociological Association in Chicago, and has a tentative go-ahead to publish a corresponding paper in the American Journal of Sociology.) Overall, they found that neighbor-related complaints to 311 were 26 percent higher in fuzzy-boundary zones as compared with adjacent areas where there were more uniform racial demographics.

One obvious counterargument to this theory that fuzzy borders are hotbeds for racial tension: Perhaps it’s simply diversity itself that causes the strife? Previous research, after all, has identified a link between diversity and discord. But when crunching their data, Legewie and Schaeffer controlled for racial diversity, as well as variables such as relative rates of poverty, unemployment, education, residential turnover, overall tendencies to make a fuss to 311, and whether residents were immigrants or English speakers. The differences persisted.

Legewie hopes his paper will inspire fellow sociologists to stop thinking of diversity in and of itself as a reason for tension between neighbors. Instead, he wants academics to broaden their lenses to consider the racial composition of the greater surrounding area as a possible factor influencing such social clashes. In these fuzzy-border cases, residents might have a certain expectation of how the culture of their neighborhood is supposed to be. But this notion may be based on the racial composition of an adjacent area; and as it turns out these people are actually living in something of a no-man’s land, a transition zone between two neighborhoods that are each racially uniform, but in different ways — and which therefore may have different local norms when it comes to issues like loud music or public drinking. Feeling out of place, these individuals aren’t able to work out differences with neighbors with a simple knock on the door, so they start trying to defend their turf by raising a stink with the city about loud parties or someone renting out their place to tourists. Or so the theory goes.

This research tells a cautionary tale about the interpersonal problems that may arise as the city rapidly changes and gentrification continues its steady forward march. When asked about how Columbia’s aggressive push into Harlem, for example, could spark interracial animosity, Legewie said that his research “would suggest that expanding gentrification and pushing past these boundaries entails potential conflict.”

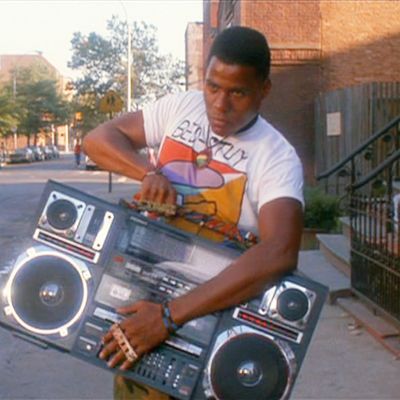

So, to get real, do these 311 rants ultimately boil down to cranky, territorial whites wailing about the proverbial Radio Raheem and his ghetto blaster? Unfortunately, 311 records lack racial information about the callers or their accused tormentors.

However, Legewie and his colleagues did look for such data by poring over comments on a popular web forum, citydata.com, where disgruntled New York City residents flock to moan about their neighbors. While the locations of the participants aren’t identified, and this sample is biased by the fact that certain types of people are more likely to access such a site, Legewie said “you clearly get the impression” that there’s an overall theme of white people complaining about black people.

As for how to temper discontent in the fuzzy-boundary zones, Legewie said, “I don’t think that there’s a simple answer in terms of a policy that addresses that issue directly.” But as race relations remain critically fractious throughout the United States and turf wars erupt — think of the McKinney, Texas, residents who apparently hurled racist slurs at the crowd of black teenagers using a community pool in June — research such as this can at least help us better understand what sorts of conditions may give rise to neighbor-on-neighbor strife.

Benjamin Ryan is an editor at large at POZ magazine, where he covers the science of HIV and hepatitis C. His work has also appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, the New York Observer, Men’s Journal, Out, and The Advocate.