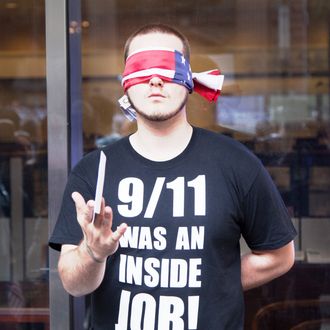

At this point, 9/11 trutherism is a punch line, and “jet fuel can’t melt steel beams” a winking joke among Twitter users. And that’s understandable: It’s frustrating to watch a group of people who seem determined to turn a real-world tragedy with causes that are pretty well understood into a tale of almost unimaginable, supervillainous government malfeasance; plus, conspiracy theories take a very real toll on society’s ability to function. But it’s sometimes easy, whether the subject is truthers or anti-vaccination activists or whoever else, to forget that plenty of otherwise normal, stable human beings hold these beliefs — and to simply write them off as crazy or stupid without attempting to understand why they hold them.

That’s what’s great about an article by Brendan James published today on International Business Times. It consists of mini-profiles of a few different 9/11 truthers. Each has a sad story (including family members lost in the attacks and in Iraq), each garners a level of comfort from their involvement in the movement, and none of them is stupid. The article is an important attempt to humanize those who believe in conspiracy theories.

This part, in particular, jumps out:

The common thread between these three believers, and others I spoke with, is the sense of isolation from regular social scenes and the reinforcement from the tightly knit 9/11 Truth community.

“It’s brutal. I will never volunteer to talk about it,” [said Bob Mcllvaine, who “lost his son, Bobby, in the north tower”]. “In my circles, people ignore it. It’s like I’m a leper. I don’t see many people anymore.” He says his wife supports him, but doesn’t want to talk about how Bobby died. She says it doesn’t matter, if even his theories are true, because it won’t bring her son back. “If she started talking about that she wouldn’t have any friends.”

When asked if most of his friends come from the movement these days, Mcllvaine said it was indeed a saving grace. “I know so many people through 9/11 Truth.” Richard Gage, too, said about half of his friends are 9/11 Truth activists. His colleague and fellow Truther, Steven Dusterwald, said his “regular” friends simply do not want to hear about it. “We’re out to bowl,” they say. “We don’t wanna hear your crazy theories.”

…

[T]hey all believe that [their] community, thanks to the disaffected millennial generation, is only getting bigger. “I think it will take about another 20 years,” [Bryan Ujueta, a bartender and musician,] said. “In about 20 years people will start to piece things together.” Gage is optimistic his group is on the cusp of finally getting some respect.

There’s such a powerful self-reinforcing inertia to these communities, especially when victory is always just over the next hill, and this inertia partly explains why debunking conspiracy theories is so difficult. Reading James’s whole story, which you should, it’s hard to imagine trutherism is going away any time soon — and it’s hard not to feel some sympathy for the people who are caught up in it.