The complexities of human-robot interaction are solid fodder for sci-fi, but they’re also starting to have increasingly practical implications. As robots become more and more prominent in daily life, it’s going to be important to build ones that humans are comfortable interacting with.

The “uncanny valley” is a key concept to this discussion. The basic idea, first proposed by the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970, is that while there’s an overall relationship between how human a robot looks and how friendly humans will find it, there’s a catch — as you approach humanness, there’s a point at which robots, from a human perspective, occupy an unnatural, uncomfortable-seeming middle ground — they’re pretty human, but still identifiably something else. As a result, they’re likely to come across as weird, if not threatening, to many people. Whereas a robot like Wall-E can be easily parsed by our brain as being robotic, those in the uncanny valley often make elicit feelings of unease because they’re close to being human, but not. Robots that are very human-seeming don’t elicit these feelings because we perceive them as basically being human.

This is a popular concept, but as Maya B. Mathur and David B. Reichling, researchers at Stanford and the University of California – San Francisco, respectively, note in a new paper in Cognition, it’s one that hasn’t received much empirical support. A lot of roboticists, in other words, think that the uncanny valley sounds good (and in certain ways intuitive), but doesn’t actually map onto how humans perceive robots. Mathur and Reichling think that past experiments into this stuff have had important limitations, and they decided to run a set of their own.

For the first set of experiments, they pulled photos of the faces of 80 real-world robots (they excluded famous ones participants would recognize, as well as toys, which might have been specifically designed to elicit an awwww reaction) and asked Amazon Turk workers about them. In the first experiment, the workers answered questions about how human or mechanical they perceived each face to be (each participant was only asked about one or the other), and how positive or negative an emotion they thought it was expressing. In the second and third experiments, another set of workers were asked to “estimate how friendly and enjoyable (versus creepy) it might be to interact with each face in an everyday situation.” After running the numbers, the researchers found evidence for an uncanny-valley curve: From left to right, faces got more likable as they got more human, then dipped into the uncanny valley, then curved back up for the most humanlike faces.

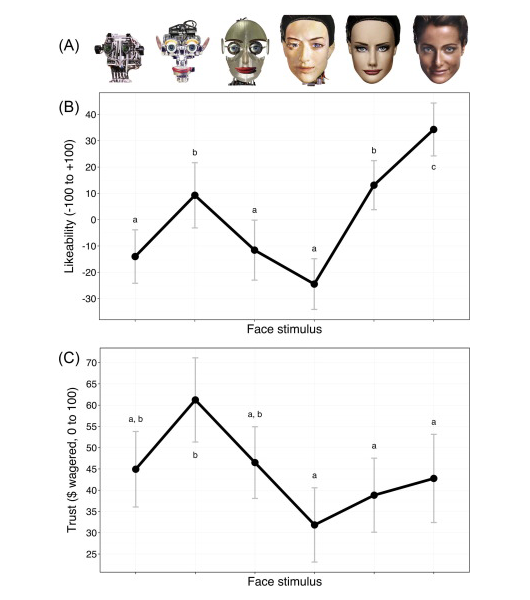

But would this curve actually correspond to how humans interacted with robots rather than how they rated them? In a second set of experiments, Mathur and Reichling sought to find out. They picked a set of six robots that they saw as having a clear progression from mechanical to human (a progression that a random sample of 12 people all agreed with them on) and had study participants rate them for likability and then play a trust game with the robots — well, with pictures of them — that involved “giving” them some money with the hope of getting a return on that investment.

Here were the results in terms of likability and trust:

Two things are worth keeping in mind here: There isn’t an equal amount of difference in “humanness” between each robot in the series, even though they’re equally spaced; and faces with the same latter designation weren’t different in a statistically significant sense — on the trust measurement, for example, all of the faces with an a were trusted about the same. So in this sample, at least, there’s stronger evidence for the uncanny-valley hypothesis on the likability front than the trust front. A second set of faces replicated this: There was a pronounced uncanny-valley curve on likability, but much less of one in the amount of money wagered.

One study doesn’t undo the other evidence that the uncanny valley isn’t real, of course. But this research is a useful step in better understanding how humans come to trust robots at a time when this is an important concept to gain a better grasp on.