Welcome to “It’s Complicated,” a week of stories on the sometimes frustrating, sometimes confusing, always engrossing subject of modern relationships.

The summer after my sophomore year, I went to Paris with a grant from my university to work on a collection of travel stories. “I plan to follow in the footsteps of Hemingway, Miller, and Stein,” I wrote in my grant application, even though none of them had ever reflected much humanity in my direction. But still, it was a direction.

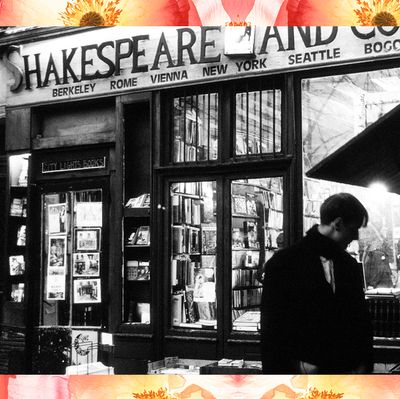

Most of my plans centered around Shakespeare and Company, the legendary Left Bank English-language bookstore first opened in 1919 by the American expat bookseller Sylvia Beach, who famously published James Joyce’s Ulysses when it was effectively banned for obscenity. It closed during the German occupation. A few years after the Second World War ended, George Whitman came to Paris as a medical warrant officer for the U.S. Army and amassed so many books that he started a lending library out of his tiny one-room apartment. Eventually, his books outgrew the room, and George used his small inheritance to open a bookstore, which he eventually named after Sylvia’s shop. It quickly became a literary institution. Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Anaïs Nin, Richard Wright, William Styron, Julio Cortázar, Henry Miller, Martin Amis, William Saroyan, Lawrence Durrell, and James Baldwin all frequented the shop, some spending hours in the upstairs reading room writing drafts of what later became books. I decided that I, too, like the famous men and women I read about, would make a pilgrimage to Shakespeare and Company and just hang out there until someone noticed me.

It took me two weeks to summon up the courage to go inside, and when I did, I met Logan, who was sitting behind the register. He rose up from his seat to shake my hand as if we had prior plans to meet. “Did you come here to apply for an internship? Are you my new intern?”

The minute he referred to me in the possessive, I forgot the introduction I had practiced all afternoon — “Hello, I’m an American writer on a research grant from Stanford and I was hoping …” All I wanted from that moment on was to never again be referred to as her but instead always as his.

“Yes,” I said. “I’m your new intern.”

*

I delighted too much in being his “intern,” showing up every night with wings flapping in my chest. At first he introduced me to customers as his intern but soon flipped it and began to say he was my intern. Most nights after the shop closed, we’d go next door to drink and play poker in the Antiquarian with some of the young men who were living in the bookstore. Everything blissed me out — gambling recklessly for change, drinking whiskey out of empty yogurt cups, but most of all, being the only girl who was invited in. I was like any girl who had been raised to have faith in a tradition that choked my imagination dead and left me with a head full of delusions, delusions that most women who have ever wanted to see themselves as somehow better than the patriarchy will likely recognize — the delusion that you might really be an exception. Let other women cry, sexism! Patriarchy! Racism! I thought. I wanted to be that girl, the impossible one who can’t actually exist, precisely because of racism! sexism! patriarchy! I thought I could be Gertrude Stein, brilliant and never in the kitchen, only I would be beautiful as well, much too beautiful to be depicted as an unfuckable hag, as Hemingway had done in A Moveable Feast, referring to Stein as “northern Italian peasant” who looked like “a Roman emperor and that was fine if you liked your women to look like Roman emperors.” In my fantasy, I would be too beautiful and too brilliant for any man to insult me.

After several nights of poker and whiskey, some of the bookstore kids suggested we all go out dancing. We ended up at a club on Rue de l’Oberkampf, the majority of us obnoxiously drunk. Lawrence was new, from the Bay Area, had a square face and square shoulders, and emitted a slightly sour, gritty smell that I found repugnant. We danced a little too close and every time I stepped back, he stepped forward. At some point, shy Angela from Italy and pompous William from New England rushed over to direct my attention to Edward, a young Brit who was as focused a writer during the day as he was sloppy drunk at night, and was now being thrown out of the club.

I ran outside to ask him what had happened.

“They said I was dancing too aggressively. But it’s all right. Let’s go. I’ll walk you back to your apartment.”

“Let me just say good-bye to everyone and get my jacket.”

When I got back inside, Lawrence grabbed me and rubbed his face in my hair. “You smell so good.”

“It’s shampoo! And conditioner!” I shouted, the whole time breathlessly aware that Logan was watching us. Whenever I felt his gaze on me, I turned into the worst kind of baby junkie, instantly high from the feeling of being looked at, desperate to find a way to make it last, and inordinately devastated when it ended. On this night, his gaze was not enough, I needed more. I yearned to go up to him and confess my feelings, but I was crowded by men — Lawrence smelling my hair, another new guy from the bookstore asking me what I wanted to drink, William appearing out of nowhere to beckon me to the dance floor, Edward waiting for me outside.

Then, suddenly, Logan reached for me, and in front of everyone, kissed me. I was his, he had declared it so.

I pulled away, stunned. “Edward is waiting outside. He said he’d walk me home.”

“I have to see you again. Can I call you?”

“I don’t have a phone.”

He wrote his number on a creased postcard and tucked it into my palm. “Hey, Jennifer,” he said, not letting go of my hand, “please remember to call me.”

I left the club stoned with joy. It was raining and Edward held his umbrella over my head the whole time, letting himself get soaked. When we got to my apartment, he kissed me on the forehead and said, “You’re a special girl,” leaving me feeling wanted by everyone. I went inside and unfolded the postcard: You’re pretty as a pillar. The next day, walking past the Pantheon, I stopped and stared at the pillars. Was that me? I wondered.

I couldn’t bring myself to go into Shakespeare’s, and instead wandered all over Paris until it was well past dark. I stopped by a pay phone in Logan’s neighborhood and called him.

“Hi,” I said into the phone. “How do you feel about booty calls?”

We were together every evening. I kept “interning” at the bookstore, but he no longer used that word.

“Jennifer’s the man in charge. She’s the boss,” he’d say to customers and the new slew of kids who came to live at Shakespeare’s. I started to love small things, like having a conversation with someone while Logan was nearby having a conversation with someone else. Even though we never touched and I never glanced over to make eye contact, it felt like we were talking to each other and it was made all the more pleasurable because no one else knew what we knew. I felt bound to Logan through secrets, big and small.

“I have a boyfriend,” I finally confessed to Logan after spending the afternoon chopping garlic.

“Should I stop kissing you?”

I shook my head no and put my fingers under his nose. “I chopped garlic all day in hopes of repulsing you.”

We laughed, charmed by ourselves — there was nothing either of us could do to repel the other. We were living in a fantasy and the clock was running out.

I had two weeks left in Paris, and Logan had a longstanding plan to take a walking trip through Norway with an old classmate. He had been inspired and encouraged by George, who spent years walking around Central and Latin America. It was supposed to be a monthlong trip, but he was scrambling to shorten it so we could see each other before I went back to the States. In his absence, it all turned sordid and gory. The morning of his trip, I left his place woozy, fighting the desire to puke my guts out on the bus ride home. As soon as I stepped into my apartment, it all came shooting out. I vomited for four days straight and dry heaved for another two. I was weak and empty. I had still written nothing and read only the books Logan had lying around his apartment. I went back to the bookstore but the woman who took over Logan’s shift said she didn’t need my help, so I loitered without purpose, following men around and listening to them talk. I was a “her” again.

On the banks of the Seine one night, I looked around at the group of people I was with and realized I barely knew anyone. A lot of the kids I had been hanging out with all summer had gone back to school. In a rare appearance, Sylvia was there, too — the stunning, seraphic, blonde-ringlet-haired young daughter of George Whitman, who ran the shop now that George was in his 80s, and had begun instituting changes with vaguely corporate qualities to them. I couldn’t stop myself from staring at her and then turning away and then staring again. One day she would become the proprietor of Shakespeare and Company. His legacy was in her hands. In the presence of a woman who was young, beautiful, capable, and hardworking. I was suddenly ashamed of having done nothing of note, of being a girl who only considered herself in relation to men and not books. I wondered what Sylvia must have thought of me, this quiet, foolish girl who hung around the bookshop every night, following Logan around like a puppy dog, blushing when he called me his intern. It was the first time all summer I cared to wonder what another woman thought about me.

I overhead a conversation about me between one of the new guys and this Irish fiddler who had been at Shakespeare’s all summer. I found him distasteful and pretentious, and he, I’m sure, found me frivolous and useless.

“What’s up with her?” the new guy asked.

“Oh, you know,” the Irish fiddler said flippantly, “she’s one of those girls who gets passed around. You could probably get with her if you wanted.”

I ran out of there without saying good-bye to anyone and Lawrence, the square-faced, sour-smelling guy from the Bay Area ran after me, seeing his chance to get me alone now that Logan was off walking in Norway. He followed me home and we fucked joylessly in my bed. The next morning, I gagged from the smell of sourness he left on my sheets.

Another evening, Edward and I polished off a bottle of whiskey and ended up drunkenly pressed up against a telephone pole, me confessing that I feared I was a sociopath and him reassuring me that I wasn’t. “But what kind of person doesn’t feel any remorse about cheating on their boyfriend? Before I came here, I thought I was in love with him. I thought we would get married. I’m a horrible person. I don’t deserve any forgiveness. How is he ever going to marry me now? I’ve betrayed him. He’ll either find out or I’ll have to spend the rest of my life lying to him. My god, I am so fucking stupid.”

“You’re not stupid,” he said, gripping my body to his.

“I’m stupid.”

“You’re a sweet girl. You’re a brilliant girl. I can see it in you. You’re smart. You have ideas. You’re impressive,” and he went on praising my intelligence while smashing his boner against my leg.

“No,” I said, trying to wriggle away.

“Listen to me,” he said, holding me tighter. “You are going to get everything you want. Do you believe me?”

“No.”

The next morning, Edward woke me up out of bed. “I think we both regret what happened last night and know what we did was wrong.”

It took me a second to realize he was referring to the clumsily, barely executed hand job I gave him with our clothes on under the covers. I didn’t think it was wrong. It seemed like exactly the sort of thing two fucked-up, young wannabe writers who had come to Paris worshiping the dead, fucked-up writers who had come to Paris before them might end up doing.

“It’s not a big deal. We can pretend like it never happened.”

Edward hesitated for a moment before speaking again. “Hey, I don’t know if you know this already, but he has a girlfriend, too. She lives in London.”

“Oh,” I said. “I didn’t know that.”

The next day, I went into the bookstore and George was there in his pajamas, yelling at customers and flipping books over one minute then being perfectly charming the next. He complimented me on my dress and handed me some crumpled bills to give to his daughter. “Tell Sylvia to buy your dress. Tell her exactly where you got it. That’s what she should be wearing.” I went upstairs to find Sylvia and sheepishly explain that I had been instructed by George to give her money and send her in the direction of my dress shop. It was our first and only exchange. We had an awkward laugh about it and when I came back downstairs Logan was there, trying to give George a bottle of Champagne.

George was headed out on his motorbike for a ride around town. He suggested instead that the two of us take it to the park around the corner. “Take the afternoon off. Go somewhere. Don’t come back for a week. Get on a train, hop off when it’s warm. Look at this guy,” he grabbed Logan’s chin and twisted it in my direction. “He needs sun.”

“Hey, George,” Logan called out as George was just about to leave. “How many women have you been in love with?”

“Every last one of them,” he answered, and then smiled and pointed to me, “and she’s the last one!” He got on his motorbike and took off.

Logan and I hadn’t even acknowledged each other yet, but like two travelers on the same point on a map headed in the same direction, we started walking, side by side, in total silence until we ended up on the Pont Neuf bridge.

“Why didn’t you tell me you had a girlfriend?” I finally asked, the most accusatory I had ever been with him. “Why didn’t you say anything when I was going on and on about how guilty I felt? Why did you let me think I was the only one doing something wrong?”

“I’m sorry. I was afraid you’d never talk to me again.”

“I’m always afraid of that.”

There was so much we were never going to tell each other, and in a way that was part of the magic, the distance we had to keep from each other made it particularly exquisite, like an art object kept behind the velvet rope in a museum. It was depressing and exciting.

We decided to take George’s recommendation and go away together for a few days. Logan arranged everything — the train tickets to Nice, the hostel with a double bed and a shared toilet. I packed just one change of clothing, one pair of clean underwear, a huge jug of cranberry juice for my urinary-tract infection, which I had probably gotten from all the enthusiastic but badly misinformed experiments in fucking that Logan and I had engaged in before he left on his walking trip, leaving me, not for the first time in my life, with a burning twat. As it often happens, the physical act of getting away gave me the psychic freedom to be myself, open to hearing anything and sharing anything. Logan told me about how on his last trip home, he found all these newspaper clippings his parents had saved from when he was born. They were so proud of him that they plastered announcements and photos of him in all the local papers. “What must the people in my town think now when they see me around the neighborhood? Do they ever wonder, how did baby Logan become that man Logan?”

I wondered it, too, asking him question after question about baby Logan, kid Logan, and teenage Logan: “If we had been classmates, I would have sat in a corner eating sour candies, too shy to do anything but watch you.” I told him about the summer my father lived with his grandfather on top of a mountain and how, when I was a kid, I thought mountains were literally sharp triangles, and I couldn’t figure out how an entire house ever balanced itself on the tip of a triangle until my father explained to me that living on a mountaintop was like living on any street I had ever lived on, the only difference being that when you lived that high up in the sky, the clouds were outside your window. You could go outside and open your mouth to the floating clouds. “My father was a cloud-eater,” I said to Logan. “One day, I’ll eat a cloud too.”

“Jenny Sass,” Logan sometimes called me, one time when we were out to dinner, going so far as to ask our waiter, “Can I get a side of sass with that?”

“Quoi?”

“Pommes frites avec ketchup,” Logan said, nudging my knee under the table.

We were so showy in those days in the south by the sea. People stopped us in the street to let us know that our happiness was infectious. That the way we were together made them nostalgic for their own days of young love. “Hold on to it. And hold on to her,” one woman said to Logan. I ran around braless in a white dress all four days. We touched each other shamelessly in public. He swam in the sea and I watched from a big slab of rock because I couldn’t swim. He convinced me to get on his back, and I did, gripping him with my whole life while he paddled us out into the clear blue waters — the farthest I had ever been. We went into shops and pleaded with the owners to give us the sandwiches they were planning to toss at the end of the day. We took a train to Monte Carlo and whispered about the preppies in cable-knit sweaters and boat shorts, and joked about which one I could con into being my sugar daddy. We tried to see a Terminator film that was being projected on a cliff but couldn’t afford the 45-euro entrance fee, so instead Logan suggested we climb up a nearby tree. I sat nervously on a branch that I didn’t think could hold us, happy to be underneath the stars, wondering as my urinary-tract infection compelled me to peel off my underwear and toss it to the ground so I could pee as frequently and shamelessly as I needed through the lattice pattern of leaves: What am I doing here?

And then, it was time to go. He was headed back to England and I was going back to America. We parted in the doorway of my apartment in the Bastille.

“Let’s not say good-bye,” I said, clinging to him and then letting go. Moments later, he came back up and knocked on my door, which I had slumped myself against, his knocks sending vibrations up my spine. It was a movie I wanted to watch again as soon as it was over, a movie I was sure I would one day write just so I could.

*

“What was created” he wrote me in the subject line of an email after many summers had passed, “and what will we create?” That summer, we had read each other like a book—one that later, rereading, I found littered with clichés. It hadn’t been very exceptional at all.

One of the last times Logan and I wrote each other, I sent him a novella I had recently completed. I had felt such a sense of accomplishment in writing it. He was going to print and bind it into a book, and we had been emailing about chapter divisions, possible titles, what image I wanted on the cover. “Does it mean you are, in a way, my editor,” I wrote with a period instead of a question mark. That was the last thing we attempted to create together and it was left unfinished. I wasn’t his. He wasn’t mine. The question he once posed had long since shifted, it had become better. I had started to ask: What will I create? It was such a relief to be released from that terrible, crushing quest to be an exception. Finally, I was someone who created without having to be asked, without waiting to be addressed.