Kolé Life Foods doesn’t really stand out at first glance. These days, lots of companies are trying to ride the wave of popular interest in neuro-everything, and Kolé, a Baltimore-based supplement manufacturer, is no exception. The company’s four “tonics” offer a variety of benefits, its website claims: one “is designed to support alertness, focus, healthy memory and brain performance, [and] energy,” for example, while another “promote[s] restful sleep and pleasant dreams.” An image of synapses lighting up adorns the homepage, and the drinks are described as “Science based tonics promoting a healthy brain.”

Kolé’s various claims haven’t been proven, according to experts Science of Us spoke with. Legally speaking, they don’t need to have been: Supplements are very lightly regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. Since these products are, in effect, categorized as foods rather than drugs by regulators — despite often advertising the sorts of benefits associated with pharmaceutical products — supplement manufacturers and marketers can make claims that would not otherwise pass regulatory muster. In the eyes of many experts these claims are frequently misleading and sometimes potentially dangerous (though there’s no evidence that Kolé’s tonics are problematic, safety-wise). But they’re legal, and they’re quite common.

Kolé, then, might blend anonymously into the humming, multibillion-dollar background of the American supplement market, were it not for the fact that it was founded and is chaired by Dr. Bankole Johnson, chair of the psychiatry department at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Johnson is an established, respected expert who has built an impressive career as an addiction researcher. The founder of ADial, a pharmaceutical company which creates drugs aimed at curtailing addiction, Johnson has published quite prolifically, was once featured in an HBO documentary on addiction, and is currently a member of Maryland’s Heroin and Opioid Emergency Task Force.

Johnson is engaging in his side business at a time when the internet is awash in conflicting information about health in general and neuroscience in particular. Online, solid science sits side-by-side with misleading claims published by conspiracy theorists and hucksters trying to separate the underinformed from their wallets, so a consumer wandering the halls of Google without a tour guide is just as likely — if not more so — to stumble upon a false theory about the CDC covering up supposedly autism-causing vaccines as they are to find credible information.

One of the most important bulwarks against this confusion is the medical Establishment, and specifically the belief that if information comes from a reputable researcher at a reputable institution it can be trusted. Doctors aren’t perfect, of course, and face the same temptations and perverse incentives as anyone else. But still: Even a hardened cynic would have to admit that the nation’s universities and hospitals are filled with countless health researchers whose overriding goal is to provide their patients and the public with reliable information, who do the best they can to sort through profoundly complicated questions of how the human body works and how to keep it healthy.

For the most part, the public trusts these experts, and this trust is profoundly important. People seem to understand this viscerally: Part of the reason the outcry over Dr. Mehmet Oz’s enthusiastic endorsement of highly questionable nutritional supplements has been so loud and so prolonged, culminating in an appearance before a Senate panel whose members excoriated him, has to do with his credentials. He’s a Columbia-affiliated heart surgeon, after all, and people expect a doctor speaking from that sort of perch to live up to ethical standards grounded in empiricism and transparency.

The problem is that it’s getting increasingly difficult for medical researchers to do so. More than ever, there are opportunities — and, in some cases, pressure — for these researchers to find ways to spin their work into revenue, both for themselves and for their universities and hospitals. This is a trend many worried observers have noted: In a 2015 article in BMC Medical Ethics, for example, academics Tim Caulfield and Ubaka Ogbogu wrote that the “increased emphasis on the commercialization of research,” while bringing benefits in the form of heightened interest in, and funding for, biomedical research, also poses a significant threat to the vital trust relationship between health professionals and the public. One risk is that commercialization-minded experts will tout products that aren’t quite ready for prime time. “There is growing concern that representations of biomedical research are inappropriately overstated,” Caulfield and Ogbogu wrote, and that the public could come to distrust medical experts as a result.

Spokespeople at the University of Maryland assured me that there are no licensing or revenue-sharing agreements in place that will lead to Kolé’s revenues flowing back into the university’s coffers. But Kolé is still seen — and, in some case, presents itself as — a positive example of the benefits of forging closer ties between the academic and business worlds. In a brief Baltimore Sun article on the company, for example, a reporter highlighted the fact that the company plans on bringing 75 new jobs to Baltimore this year. And when I first reached out to Kolé, a spokeswoman there sent me a link to a Washington Post article which, while not mentioning Kolé by name, leads off with the observation that “Maryland universities have ramped up efforts in recent years to help students and faculty turn their discoveries into growing businesses[.]” The company also has an office at bwtech@UMBC Research and Technology Park, a University of Maryland, Baltimore County, office park dedicated in part to bridging the divide between the University of Maryland research ecosystem and local entrepreneurs.

Kolé only very recently dropped promotional claims that had in some cases been on its website for a long time — shortly after I asked Johnson about these claims last month, many of them disappeared from Kolé’s website altogether, in some cases replaced by more modest language (the company, as I’ll explain, says this is a coincidence). Then, Kolé threatened litigation against me and my employer.

Overall, Johnson didn’t seem happy that a journalist was inquiring skeptically about his side business, but it’s important to shine a light on what’s going on here: Kolé is a fascinating case study in what happens when credentialed, legitimate science and profit-driven, science-ish entrepreneurship collide — especially at a time when various forces are blurring the boundaries between the two.

***

If you had gone to the website of Kolé Life Foods before about a month ago, you would have seen some rather impressive claims. As captured in a PDF of how the site appeared back then, Kolé claimed its four “tonics” offered all sorts of benefits. “These proprietary blends contain a complex mixture of multiple nutraceuticals at the right relative concentration and amount to enter the brain and enhance certain desired functional states,” the site read.

Among other claims, here’s what Kolé said its tonics could do:

— “The delicious citrus flavor of Kolé Inspire enhances alertness, focus, memory, brain performance, energy and nutrient replenishments to prevent hangovers.”

— “Ignite promotes and extends libido and sexual excitement and performance with its mixed berry taste.”

— “Our Happy blend enhances mood, tranquility, bliss, and a sense of well-being.”

— “Dreams, our tropical blend is formulated to promote quality restful sleep and pleasant dreams in everyone. Dreams can also be taken to prevent jet lag when taken at the beginning of a long flight.”

The benefits of the tonics came from their nutrients, the site explained. “Riboflavin an essential nutrient required for numerous cellular processes including the balance of monoamines in the brain… Chromium an essential trace element helps with blood sugar control, depression and increases libido… Magnesium is used to calm the nervous system [sic throughout].” At the bottom of the each page on the website — you usually had to scroll past a lot of exciting claims to get there — was disclaimer language: “These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. These products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

Given his lofty perch in the research world, it’s unsurprising that Kolé’s founder is all over the website’s “About” page, his expertise touted: “Doctor Bankole Johnson, an award-winning neuroscientist and founder of the Company, formulated each Tonic with amino acids, vitamins, minerals, and herbal ingredients, added loads of great taste (but no calories) – making Kolé Tonics the future of function,” the language reads as of May 10. And in copy that has since been excised from the site but which persists elsewhere, a mention of him sits alongside some rather straightforward claims about Kolé Tonics’ effects: “He has formulated four Kolé functional tonics that can enhance mental agility (INSPIRE), induce a sense of bliss and tranquility (HAPPY), enhance sexual intimacy and performance (IGNITE), and promote sleep (DREAMS) [emphasis in the original].”

In a lengthy “Message from Dr. Johnson” posted further down the current “About” page, Johnson explains the origins of his interest in the tonics he is selling:

My own father was a specialist in nutrition, a rare specialist for a physician in those times, and as early as I can remember (perhaps at about the age of 4 years), was trying out my sister and I on various supplements, which he would make us as shakes, to help support our brains. All of this, more than five decades ago, long before anyone had awakened to the thought of creating functional drinks for the brain. Who knows whether his experiments worked on us (although I was able to play chess blindfolded with my father as a young child – a skill I have since lost). What truly mattered was that my father was willing to try…and therein lies the kernel of my story.

…

I will not bore you with stories of how complex developing these beverages have actually become, or the many challenges in formulation and production that had to be overcome. Also, it might be quite boring, at this stage, to describe how many naturally occurring nutrients that impact the brain in the concentrations needed are unpalatable and sour, and how, through many rounds of focused groups with taste testers, all these were integrated into what I think are delicious tasting and refreshing beverages. All those were themselves interesting paths of following the scientific curiosity of seemingly simple questions, which, in the end, were not a simple as they might have appeared.

Elsewhere on that page, Johnson explains that “the key to optimizing the brain would appear to be in the regulation of the balance and interaction between brain chemicals” (this language, and the above excerpt, are also all current as of May 10). Until recently, Johnson also touted the beverages in a series of videos on Kolé’s now mostly barren Youtube channel — we’ll get back to that.

In light of all this, and in light of Johnson’s status as a researcher, a curious consumer not versed in the finer points of nutrition and neuroscience could be excused for thinking his tonics have been proven to do what they purport to do. But every expert who spoke or corresponded with Science of Us about the claims that were until recently on the Kolé website — and which were current at the time those experts commented — said that many of the claims appeared to be overhyped or unfounded.

“Man, this is crazy stuff,” said Caulfield, the co-author of the paper about research commercialization, and the Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy at the University of Alberta. “And there is a whole bunch of science-y-sounding jargon. Given that he is a scientist, this is even more irritating than usual. I don’t know of any robust studies to support the idea that any of his products would have some kind of clinically meaningful impact. Most of the stuff is complete nonsense.” (Caulfield’s area of academic training is the law, but he has been doing interdisciplinary work for decades, and has been published extensively on research ethics, the commercialization of science, and other related fields.)

“This looks like the usual marketing fluff,” said Dr. Marcus Munafo, a biological psychologist at Bristol University in England. “Most (if not all) of the things present in these drinks are available in a normal, healthy diet anyway. Those that aren’t represent herbal products where the health claims, for the most part, aren’t supported by robust evidence.” (Biological psychology is a field closely related to behavioral neuroscience.)

He continued:

It’s worth bearing in mind that many herbal products may well have some beneficial effects (e.g., St John’s Wort and depression), but this is really just 18th/19th century pharmacology - messier drugs than the more targeted options available today. The idea that because something is “natural” it’s somehow better for you is generally misguided.

I’m sure that there are some studies to back up most of the claims they make, but [the] key point is this: If you haven’t shown that *your* drink elicits the effects you describe relative to placebo, then your claims are fairly shaky. These drinks may be pleasant to consume, but I doubt they will have noticeable effects along the lines they describe (beyond a placebo effect).

Dr. Peter Etchells, a senior lecturer in biological psychology at Bath Spa University, also in England, offered a similar critique. “In general, all of the descriptions read like scientific guff that doesn’t actually explain whether the drink works,” he said in an email. “For example, with the ‘Happy’ drink, there’s a difference between saying (a) that Tryptophan is a precursor for serotonin, and (b) saying that this drink will make you feel happier. (a) is true, whereas (b) is untested and unproven. Interspersed with the sciencey-sounding stuff is utter rubbish, though. Again, for ‘Happy’, the second line is ‘the great taste of Blue Raspberry flavor helps to stimulate mood’. This is rubbish.”

“In short,” continued Etchells later in his note, “these products ring all of the usual alarm bells about nonsense ‘brain’ drinks. Gratuitious [sic] use of the word ‘detox’, which doesn’t mean anything, and vague references to science - in the ‘bibliography’ section of the website, they refer to a wealth of studies on citicoline that have no bearing on the products themselves (e.g. The role of citicoline in ischemic stroke). If they want to properly back up these claims, then robust trials of the actual products themselves need to be conducted, and I can’t find anything of the sort in the research literature.”

According to Dr. David Seres, director of medical nutrition at Columbia University Medical Center (he is also a member of the Consumer Reports medical advisory board and is frequently quoted on the misleading nature of some supplement claims), Kolé’s claims mixed up two separate questions: whether not having enough of a given nutrient or substance can cause problems, and whether, in someone who already has a healthy amount of it, ingesting more can provide any benefits. “These substances, when they’re deficient, cause problems, but in most people there is no deficiency, so supplementation has no benefit, and moreover it may carry risks,” he said. Caulfield said many claims about supplements (not just Kolé’s) are based on this misunderstanding. “I think it’s almost a truism now that most supplements aren’t necessary — you get your vitamins and nutrients from the food you eat,” he said. Indeed, a “bibliography” document published by Kolé cites studies dealing with nutrient levels in patients with cognitive decline, delirium, or addiction — findings which are likely not relevant for a product marketed as benefiting the general population. (In one of the letters he sent New York Magazine’s external counsel, Kolé’s attorney pointed out that in general “very little research is done on healthy people,” though he also noted that some of the studies cited by Kolé were conducted on healthy populations.)

“If somebody told me the chair of an academic psychiatry department was doing this I wouldn’t believe it,” said Elizabeth Woeckner, president of the advocacy group Citizens For Responsible Care and Research, in an email. (Woeckner does not have specialized training in these areas of science, but has been published in the area of medical ethics.)

It’s important to note that some of Kolé’s claims about its products’ individual ingredients do have some empirical support. Some of the tonics contain caffeine and melatonin, for example — well-studied substances that are believed to have particular effects. Etchells also pointed out in an email that there appears to be some evidence that citicoline (or cognizin), which is one of the ingredients touted, “may improve things like working memory and attention in healthy individuals [his links].” But “even if citicoline has an effect,” he explained, “you’d need to be taking it consistently for a while in order to see that effect. Chances are, if you have a single drink containing 500 mg of citicoline, it’s probably not going to make a noticeable difference — in the two studies I mention above, in one participants received citicoline over a period over 28 days, and in the other they were given it in conjunction with caffeine (so it’s impossible to isolate the effects of citicoline).” Moreover, as Munafo pointed out, pointing to tests of individual ingredients in a drink is not the same, evidence-wise, as pointing to controlled evaluations of the entire drink. Kolé did not respond to a request for studies demonstrating the effectiveness of the tonics themselves, as opposed to ingredients contained in them.

When I first reached out to Johnson for comment, he forwarded his request to a Kolé spokeswoman, Sarah Rose Attman. She sent me a statement which included a “Summary of Select Ingredient Clinical Trials.” With the exception of studies covering well-known substances like caffeine, here Kolé once again mostly followed the logic-leap playbook mentioned by Seres and Caulfield — assuming that because someone is suffering from illness from not having enough of a substance, giving a healthy person more of that substance will also bring benefits.

In other cases, there were important disconnects between the studies cited by Kolé and what they might prove about the tonics themselves. For example, to support the purported benefits of Happy, Attman’s summary cited a 2006 study which showed that over the course of a 14-day experiment, taking one gram of tryptophan three times a day “increased the recognition of happy facial expressions and decreased the recognition of disgusted facial expressions in female, but not male, volunteers.” According to the ingredients page on the Kolé website, Happy contains a 780-milligram “proprietary blend” of substances, some unspecified amount of which is is tryptophan. Even if that blend is mostly tryptophan — say, for argument’s sake, 750 milligrams — and even if the person drinking Happy is a woman, that would be just one quarter of the daily dose that, ingested continuously over two weeks, appeared to elicit what could be interpreted as a positive effect in a controlled laboratory setting. Without a rigorous test of the drink itself, then, there is little good reason to think a single bottle of Happy will have salutary real-world effects on mood.

There was a similar disconnect in Kolé’s claim that a study listed on its bibliography supports the idea that Ignite improves sexual performance. In that study, published in European Urology, “the on-demand oral administration” of six grams of a substance called L-arginine glutamate and six milligrams of a substance called yohimbine hydrochloride (or HCL) an hour or two before sexual intercourse was shown to be “effective in improving erectile function in patients with mild to moderate ED.” Two things jump out: The first was that the patients in question had sexual dysfunction, while Ignite is marketed to the general population. The second is, again, dosage — Ignite’s proprietary blend consists of 3,805 milligrams of L-arginine glutamate and yohimbine HCL, total, which looks to be only some fraction of the L-arginine dosage that was shown to be effective in the study when the substances were ingested by subjects with erectile dysfunction shortly before sex.

So it appears that in many cases Kolé cites as evidence literature that doesn’t quite match up with the claims that were on the company’s website. In one of his emails, Etchells pointed out the FDA disclaimer on Kolé’s website, and explained that while “wording of their drinks is clever, in that they don’t actually say that they can treat any mental disorders … there is the heavy implication for Inspire and Happy that they can be useful for depression and/or anxiety, which I find disingenuous.” Indeed, prior to the language change on the website, the drinks made rather straightforward assertions about their benefits: Recall that the language for Inspire stated that it “enhances alertness, focus, memory, brain performance, energy and nutrient replenishments to prevent hangovers,” while Happy allegedly “enhances mood, tranquility, bliss and a sense of well-being.”

On April 7, after I had reached out to Johnson for comment and had been referred to Kolé’s PR staff, I got a call from Kolé’s counsel, Eric Heyer. Heyer informed me that Johnson was “preparing” a defamation lawsuit against me. It wasn’t for anything I had published — this article was still in progress at that point — but rather because I had sent some of Johnson’s colleagues at the School of Medicine emails asking if they wanted to comment, on or off the record, on the claims being made by the chair of their department for his outside venture (none of them got back to me, anyway). I put Heyer in touch with New York Magazine’s external counsel, and, that weekend, Heyer confirmed to him that Johnson and his company were prepared to sue. After we agreed to a further round of questions and answers, the threatened lawsuit was put on ice. I started submitting all my questions to Kolé through our attorney, and the company responded through Heyer.

Right around the time Heyer first called me to threaten a lawsuit — possibly the same day — a new line appeared in the disclaimer at the bottom of the Kolé website: “Professor Johnson’s role as founder and Chairman of Kolé Life Foods has no affiliation with his role as a faculty member at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. The University of Maryland does not endorse Kolé Tonics or other commercial products.” More importantly, around that same time the company also toned down many of the claims it was making about its four beverages. We’ve created a PDF displaying the old and new language (as of May 10) for each tonic, but to take one example, here’s how the full product description for Ignite initially read [sic throughout]:

Ignite promotes and extends libido and sexual excitement and performance with its mixed berry taste. Scientifically formulated to increase stamina, blood flow and staying power. Vitamin E known as important antioxidants that protect the brain and other organs from damage. It helps support sex drive and boost libido. Chromium an essential trace element helps with blood sugar control, depression and increases libido. L-Arginine is an amino acid that quickens the repair time of damaged tissue Ginseng Root Extract promotes nitric oxide and thereby nitrergic transmission to increase sexual function. Oat Straw Extract helps boost energy by bringing more oxygen to the brain and helps boost libido and sexual excitement Epimedium Grass Extract inhibits the activity of PDE-5, and has reported aphrodisiac effects. N-Acetyl-L-Tyrosine increases drive and enhances energy Yohimbine Hydrochloride enhances vasodilation in men and engorgement in women

And here’s how it reads as of May 10:

Ignite is formulated with a delicious mixed berry taste and ingredients designed to help support healthy sexual response.Vitamin E is an important antioxidant.

Chromium is an essential trace element that can help manage blood sugar as part of a healthy diet and helps promote a healthy libido. L-Arginine is an amino acid that supports healthy recovery.

Ginseng Root Extract promotes nitric oxide, which may help sustain sexual function. Oat Straw Extract promotes energy and excitement. Epimedium Grass Extract has reported aphrodisiac effects. N-Acetyl-L-Tyrosine supports drive and energy.

Kolé claims this timing is coincidental, that it had been planning all along to update and refine its language. And the company had, in fact, migrated to a new website, from Kolelifefoods.com to Koletonics.com, around the time of the legal threat (the former now redirects to the latter). But when the new website first launched, it still contained the original claims for the four tonics — I sent emails as late as April 6 in which I linked to, and copied and pasted, the old claims directly from the new site. When I followed up about this, Kolé, through Heyer, said that this was simply due to the order in which its third-party web company had decided to update various language on the site.

Either way, in some cases, the language that was changed, or which disappeared, had been on the site for a very long time. The oldest version of the old Kolé site captured by the Wayback machine, for example, is from January 2014 and contains this copy: “Kolé Alive enhances alertness, focus, memory, brain performance, energy, and nutrient replenishments to prevent hangovers. The Happy blend enhances mood, tranquility, bliss and a sense of well-being. Dreams [emphasis in the original].” (It appears that at the time there were also longer, more detailed product descriptions, but they are no longer available on the archived site.) Kolé had been making some of these claims for years, in other words, and changed them at about the same time it was threatening to sue a journalist who was working on a story about them.

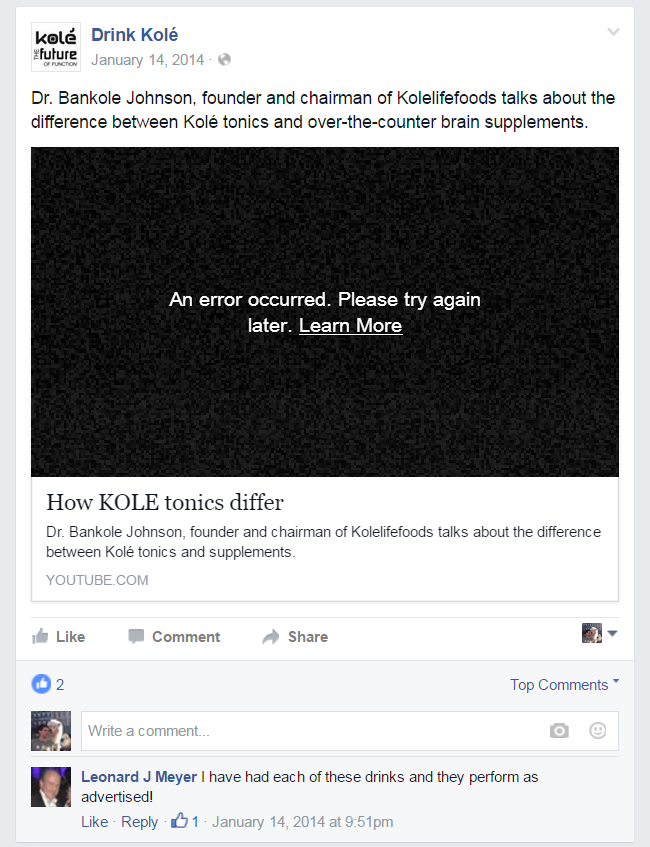

Sometimes in the last few weeks, the YouTube videos of Johnson himself touting his tonics’ benefits also disappeared from Kolé’s YouTube channel (unfortunately, I didn’t save them, and now I can’t find them online anywhere).

In a letter, Heyer explained that it had simply been a two-and-a-half-year-long accident that the videos were even up in the first place:

The videos that were previously available on YouTube were made back in late 2013 with the assistance of an individual who is no longer employed by Kolé Life Foods. The videos were never intended to be made available to the general public and when Dr. Johnson realized that they had been he asked that they be removed from the YouTube website on December 24, 2013. Unfortunately, the former employee failed to do so and Dr. Johnson and the company did not have access to the password to remove the videos after the former employee left the company. It was only recently that the company was finally able to ensure that the videos had been removed. While Kolé Life Foods has no obligation to forward the emails to you or Mr. Singal, as counsel for Kolé Life Foods, let me assure you that I have in my possession multiple emails dated December 24, 2013, wherein Dr. Johnson requested that the former employee remove the videos from the YouTube website.

I didn’t follow up about those emails, but three weeks after Johnson allegedly sent them, one of the videos was, in a post that as of this writing is still live (though the video has been taken down), published on Facebook:

(The author of the comment, Leonard J. Meyer, appears to serve on the board of ADial with Johnson.)

In a response to detailed questions Science of Us sent Kolé about the company’s claims, Heyer sent back a letter that incorrectly anticipated the point of this article. “The phrasing of several of Mr. Singal’s questions suggests that he (or, perhaps, the medical ‘experts’ that he has consulted) incorrectly believes that dietary supplements such as Kolé Tonics must be proven to be ‘safe and effective’ in order to be made available on the market.” Under federal law, the letter continued, supplements like the ones Johnson is selling are “regulated as a subset of foods,” not as pharmaceuticals, and therefore do not need to meet any such standard. Elsewhere, Heyer cautioned that Kolé could pursue litigation targeting not only myself and New York Magazine, but also my sources, arguing they had no grounds to evaluate Kolé’s and Johnson’s claims if they weren’t familiar with that distinction between products that are and are not subject to that “safe and effective” threshold. The letter also noted that Kolé plans to de-emphasize Dr. Johnson’s role in the company.

***

Johnson, formerly the chair of the department of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences at the University of Virginia, was hired by the University of Maryland in 2013, and was able to set up Kolé Life Foods close to his new job: the contact page says the company is located in Baltimore’s Harbor East neighborhood, but a Baltimore Sun article from late February reports that the company is headquartered at the aforementioned bwtech@UMBC Research and Technology Park (both offices are within 15 minutes drives or so from the University of Maryland School of Medicine). Bwtech@UMBC “brings research, entrepreneurship, business leads, prospective clients and economic development in the Maryland region to one singular place,” according to its website, and is affiliated with the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “Kolé Life Foods is not an incubator tenant at bwtech@UMBC Research and Technology Park,” said Lisa Akchin, associate vice president of UMBC, in a statement. “The company has signed an affiliate agreement for access to limited services and programs. The agreement explicitly states that affiliate status does not imply endorsement of the company or its products.”

The University of Maryland noted in a statement that Kolé is an entirely separate venture that has no connection to Johnson’s role as a department chair at the U of M School of Medicine, and didn’t address questions about Johnson’s arguably overblown claims about his product’s benefits. “Dr. Johnson or any other faculty member is expected to conduct outside activities so that they do not interfere with their responsibilities to the University,” the statement read. “We are aware of Dr. Johnson’s outside business activities. These activities are reviewed regularly to ensure compliance with University System of Maryland and School of Medicine policies. We will take appropriate action if any aspect of a faculty member’s outside business activities is detrimental to that faculty member’s University work.”

So there is no evidence to suggest Dr. Bankole Johnson is violating University of Maryland policy — nor is there any evidence to suggest he or his company is breaking the law. That’s not the point here. The point, contra Heyer’s letter, is that there is evidence that Johnson, a big-name physician and researcher, advertised his tonics in a way that raised the eyebrows and the skepticism of several scientists and scholars, in part due to the potential of those claims to mislead consumers. And there’s also evidence that these claims were significantly toned down when a journalist inquired about them — though, again, the company claims these two events were unrelated.

Even if it doesn’t constitute an illegal activity, there are real societal downsides when researchers promote scientific-sounding commercial products with claims that aren’t scientifically proven. “The public puts a lot of trust in academics — and studies have told us that,” said Caulfield. “Researchers and scientists working at universities are among the most trusted people in the world … and studies tell us that consistently. When researchers start selling products and are involved with industry, research also tells us that trust goes down.” This is what his BMC Medical Ethics paper pointed out, and Johnson and his company could serve to illustrate the kind of risk Caulfield and his co-author warned against in it. As Caulfield noted, “In a world where we’re bombarded with scientific information and so much of it is conflicting, and so much of it is confused, it’s a shame if that one voice that is out there that’s supposed to be trustworthy becomes tarnished by these kinds of activities.”