Eslom, born in Uganda in 1994, had an adolescence marked by trauma: His mother died with he was 13; at age 15, he suffered a serious injury to his arm. He disappeared for a few months afterward, cutting himself off from his community. When he returned, according to case reports, he was different: quick to anger, easily irritated, taking an unusually long time to calm down. He was more fearful, had a harder time sleeping. He pulled away from his old friends.

Eslom, according to the people who have studied his behavior, has post-traumatic stress disorder. He’s also a chimpanzee, one of several that scientists have pointed to as evidence that animals process trauma much like we do, with, in the worst cases, the same lingering long-term symptoms. “If animals can experience joy — and I don’t know anyone in their right mind who would say animals can’t experience joy — then they can experience the other side of the coin,” says Marc Bekoff, a professor emeritus of evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Traumatic events aren’t limited to humans; neither, it seems, are the mental scars they can leave.

Not everyone who deals with trauma will suffer lasting effects. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs, around 60 percent of men and 50 percent of women will experience some kind of traumatic event over the course of their lifetimes, but just four percent and ten percent, respectively, will ever meet the threshold for PTSD. For obvious reasons, there are no similar statistics about other species. But as researchers focus more attention on animal emotions, they’re also gaining a greater understanding of the emotional and psychological problems that can plague animal minds.

In a 2011 study in the journal PLoS One, for example, a team of researchers compared published reports of apparently traumatized chimpanzees, like Elson, against the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ diagnostic criteria for PTSD. The animals varied in their traumatic experiences — some had been separated from their families, or socially isolated, or been the subject of invasive lab experiments — but they showed striking similarities in their behavior, exhibiting signs of anxiety and depression much like humans with the disorder. They picked fights, or had trouble paying attention to any one thing, or had extreme reactions to touch.

“It seems that animal mental illness can be triggered by many of the same factors that unleash mental illness in humans,” Shreya Dasgupta wrote for the BBC last year. “That includes the loss of family or companions, loss of freedom, stress, trauma, and abuse.” It also includes war, a human activity with repercussions that extend beyond our species; there’s a significant body of research, for example, on war dogs who return home with new psychological baggage. Walter Burghardt Jr., the chief of behavior medicine at Lackland Air Force Base’s Military Working Dog Hospital, in Texas, told the Los Angeles Times in 2012 that an estimated ten percent of U.S. military dogs sent to Iraq and Afghanistan develop “canine PTSD.”

“This is something that does not get better without intervention,” he said. “They’re essentially broken.” Other researchers have noted that some civilian dogs show similar behavior after surviving abuse, natural disaster, attacks from other dogs, or even severe thunderstorms.

Thus far, animal PTSD has been studied mostly in captive or domesticated animals — primarily because it’s easier to keep tabs on animals’ behavior and symptoms in these settings — but there’s a small body of research investigating how trauma plays out in the wild. A study of baboons published earlier this year, for example, found that the effects of childhood trauma — things like losing a parent, or having to compete for food — persist into adulthood, worsening the animals’ health and even shortening their lives.

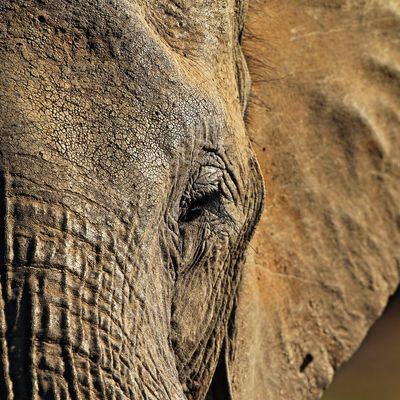

A 2013 study in Frontiers in Zoology found evidence for a similar phenomenon in elephants, reporting that traumatic events from years and even decades earlier appeared to have a long-lasting negative effect.The study authors followed a group of young elephants at South Africa’s Pilanesberg National Park who had been relocated from Kruger National Park, the site of a mass elephant culling over several decades in the later part of the 20th century. The animals showed strange reactions when the researchers played a series of elephant sounds — they ran away from familiar calls, and showed signs of confusion at unfamiliar ones (the typical response to such calls is for elephants to group together as a defensive measure).

“Long-lived species such as elephants, cetaceans, and non-human primates naturally exist in complex societies where behavior and fitness is strongly affected by social relationships,” the authors wrote. “These critical facets of social living are often compromised in wild populations subject to human disruption, and missing in the majority of captive environments. Of particular concern, given the longevity of such species, is that the marked effects of these disruptions persist in the long term.”

In more controlled settings, though, a handful of cases have shown that therapeutic techniques can ease an animal’s symptoms: One of the other chimpanzees in Elsom’s study, for example, showed some progress with other chimpanzees after interacting with caregivers, letting them groom and tickle him. And Bekoff has worked with an elephant sanctuary, he says, where caregivers work to emotionally rehabilitate traumatized elephants — caregivers cycle through to provide 24/7 “constant contact, love, touch,” he says — before releasing them back into the wild. Human intervention can traumatize animals, in other words, but it can help them heal, too — and as we learn more about the emotional lives of other species, we’re also learning more about how to set them right.