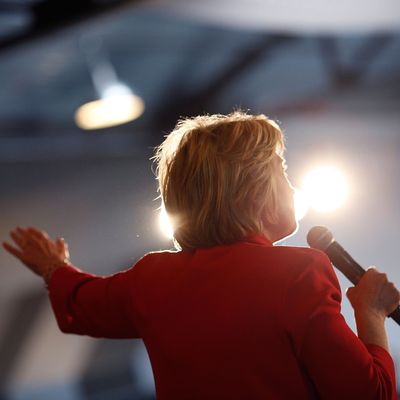

Hillary Clinton is not a natural politician, nor is she a natural public speaker. This is not my opinion; this is Clinton’s own. “Look, I have said before and it won’t surprise anybody to hear me say it, this is not easy for me,” Clinton said at a debate in March. “I am not a natural politician, in case you haven’t noticed, like my husband or President Obama.” She has to work hard, in other words, to achieve something that appears to be an innate gift for many of her peers.

If this was meant to endear the voting public toward her, it’s not clear that it worked. Last week, Jamelle Bouie used Clinton’s own “natural politician” line in perhaps exactly the opposite way that Clinton’s camp hoped it would be used, as an example of the reasons why liberals are worried that “she doesn’t inspire in ways we expect our presidential hopefuls to inspire”; a Salon piece echoed that sentiment, repeating the line that she lacks “the charm of her husband or the charisma of Barack Obama.”

Her public-speaking style in particular has been picked apart — and much of that commentary, as many others have pointed out, reveals evidence of a societal bias toward women who seek positions of power. This is an important point. But the discussion around Clinton’s admission that she is not a “natural” also hints at another hidden bias, one that is not often discussed but is nonetheless counterproductive. Research in social science suggests that when people are given a choice between someone who demonstrates natural talent and someone who is a hard worker, most say they prefer the hard worker — but their behaviors suggest the opposite. Most people prefer the natural, and often by a wide margin.

Expert musicians, for example, will tell you that dedicated practice matters more in their field than natural ability — though if they are asked more indirectly, they’ll show a preference for the naturals. As a matter of fact, this is exactly what they told University College London psychologist Chia-Jung Tsay, who has done some intriguing research on the perception of naturals versus strivers. In a 2011 study, she gave musicians short biographies of two pianists: One indicated that the pianist was a gifted musician, and the other focused more on that pianist’s work ethic. She then played for them two short pieces of music, supposedly played by each of these individual musicians; in reality, it was one musician playing both pieces. Tsay asked her study volunteers to judge the proficiency of each player they heard, and most of them ended up preferring the one who was supposedly the natural talent. This, despite the fact that before this portion of the study began, they’d told Tsay that effort matters more than talent when it comes to mastering music.

A few months ago, Tsay published the results of another study on naturals and strivers, this one involving entrepreneurs. Like the musicians experiment, she had some of her study volunteers — all of whom had some sort of business experience — read a short bio about an entrepreneur whose accomplishments were largely due to hard work, and another about an entrepreneur who mostly got by on natural talent. Tsay then played for her participants a recording of a brief investor pitch, supposedly delivered by the entrepreneur from the bio they’d just read. Again, the results showed that people prefer talent over effort: When the entrepreneur had been described as a natural, the listeners thought the pitch was more convincing than when the entrepreneur had been described as a hard worker.

All of which suggests that when people comment on Clinton’s lack of innate talent as a politician or public speaker, what they mean is that it doesn’t matter how hard she tries — she will never catch up to the naturals. In that same entrepreneurs study, in fact, Tsay came up with some figures to demonstrate exactly how difficult it is for strivers to overcome the talent bias. To have the same appeal as the naturals, hard workers need approximately four and a half years more management experience, 28 more IQ points, and an additional $40,000 in seed money for their entrepreneurial ventures.

This is a problem, as Tsay and psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman pointed out recently in Harvard Business Review, because the literature — not to mention common sense — would suggest that it takes both natural ability and effort to succeed. “Both talent and effort seem to be relevant to skill development and eventual levels of performance, and we should not assume that talent is necessarily less malleable than effort, or vice versa,” they write, referring to a 2015 paper by Kaufman and Angela Duckworth (she of “grit” fame).

Duckworth, incidentally, in her recent best seller, Grit: The Power and Passion of Perseverance, briefly nods to Clinton’s supposed lack of natural talent as a politician or a speaker — more specifically, though, Duckworth is interested in the public perception of Clinton as a hard worker. She notes that many people tend to observe that while Bill Clinton is seen as a gifted politician, “Hillary has to contort herself into the role. Bill is a natural; Hillary is merely a striver. The unsaid but obvious implication is that she’ll never quite be his equal.”