Much has been said about the awkwardness of meeting someone once, and then meeting them a second time — only to embarrass yourself because it’s obvious you’d forgotten about that first introduction. Less, though, has been said about the opposite kind of embarrassment: Memorizing a person’s face in an instant, and being able to recall it later even if you only met once, and briefly at that. (“Ah, yes, I remember you. We talked for about four minutes at a networking event two and a half years ago.”)

Such is the everyday creepiness of life as a super-recognizer, a term coined by researchers at Harvard and University College London to describe people who are uncommonly skilled at face perception. In one paper, super-recognizers told a team of perceptual psychologists that, like so many fictional heroes with extraordinary abilities, they often feel the need to hide their superpowers; we mortals simply wouldn’t understand. “I do have to pretend that I don’t remember [people],” said a then-26-year-old Ph.D. student identified only as C.S., “because it seems like I stalk them, or that they mean more to me than they do when I recall that we saw each other once walking on campus four years ago in front of the quad.”

With the discovery of super-recognizers in 2009 came a new way of thinking about face perception: The ability to recognize faces seems to exist on a spectrum, with the 2 percent of the population who are super-recognizers on one end, and prosopagnosiacs — that is, the 2 percent who are unable to recognize familiar faces (including their own) — at the other. Previously, prosopagnosia was considered a disorder or an impairment; now many psychologists believe it’s just on the low end of normal visual functioning. And most of us, as is the case with any bell curve, are somewhere in between the two extremes.

You can test your own skill at facial recognition, through this test The Cut has adapted with permission from University of Greenwich psychologist Josh Davis:

A quick note: If you scored very high on our version of this test, Davis would very much appreciate it if you would also take a lengthier version, which may be used in his scientific research on super-recognizers.

What it means to have scored very high on this test, however, is something scientists are still working out among themselves. Not so long ago, psychologists in this field of study argued that children did not develop in full the ability to discriminate between different faces until about their tenth birthday. But newer research has shown that infants demonstrate preferential attention to faces within an hour of birth: A newborn will follow with her eyes or head even the simplest representation of a human face longer than she will follow just about any other stimuli.

Clearly, it seems, there is something very special about human faces. ”I usually hate evolutionary B.S., but it’s probably true that face recognition ability was really important for our ancestors,” MIT cognitive scientist Nancy Kanwisher, who has studied face recognition, has said. “So it’s not crazy to … hypothesize that some aspects of face perception may be evolved.”

A few things about the skill can be ruled out. For one, a talent for super-recognizing isn’t correlated with IQ; Oliver Sacks, after all, was a brilliant neurologist and writer, and he was famously face-blind. So, for that matter, is Jane Goodall, whose trouble with discriminating between faces even extended to the chimpanzees she studied. And super-recognizing also seems to be something different from plain old memorization. In an intriguing study published earlier this year in PLOS ONE, a team of scientists from Switzerland, the U.K., the Netherlands, and Germany tested two super-memorizers, a neuroscientist and a lawyer who have each competed and “had exceptional success” at the World Memory Championships.

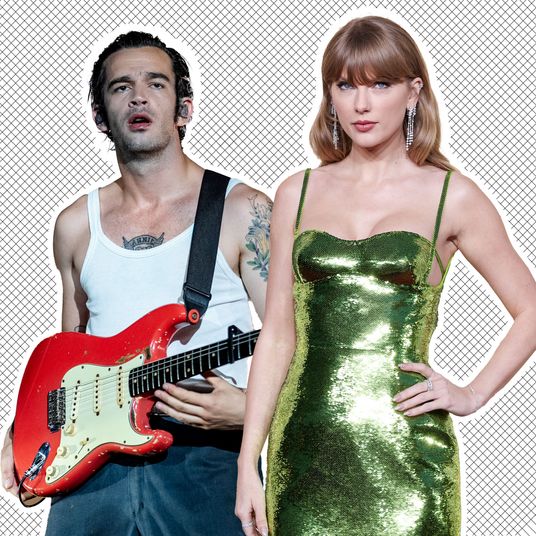

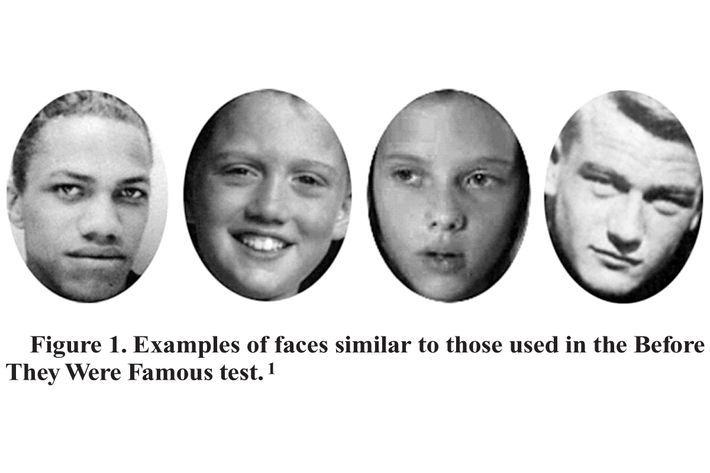

When the researchers asked them to take on tasks specifically designed for identifying face recognizers — things like the so-called Before They Were Famous test, in which study participants must name the celebrity from a photo taken in childhood or adolescence — their scores were in the normal range. Nothing special. Put another way: This was one context in which the super-memorizers had nothing on the super-recognizers, and that suggests that super-recognizing is not the result of rote memorization. In contrast to super-recognizers, “exceptional memorizers are made, not born, and do not possess exceptional visual abilities,” the authors of that study write.

In case you’re curious, the answers to the Before They Were Famous test pictured above are these: From left to right, that’s Malcolm X, Bill Clinton, Scarlett Johansson, and John Wayne. Another skill of super-recognizers, by the way, is that they are very, very good at playing the game What Else Was He In? You know this game. It’s the one where you rack your brain while watching a movie or television show — Where have I seen this actor before? A super-recognizer, for example, likely noticed immediately on a recent Game of Thrones episode that the English actor cast as Walder Frey also plays groundskeeper Argus Filch in the Harry Potter series.

But back to the science. As the super-memorizers study hinted, previous research in twins has already suggested a potential genetic component here, as identical twins tend to be more similar in their face-recognition prowess than are fraternal twins. Interestingly, genetics also play a part in an individual’s personality traits, which are thought to be highly heritable. Take extroversion, for example. It’s possible that extroverts, those social butterflies that flit among us, are more interested in faces, since they are more naturally inclined toward sociability. And so perhaps they spend more time looking at faces — which, in turn, makes them better at facial recognition. That’s what a team of Chinese researchers concluded in a 2010 study, which established a link between extroversion and superior face recognition. “We found that extroverts who have better social skills correctly recognized more faces than introverts,” they write in the journal Communicative and Integrative Biology. The extroverts weren’t especially skilled at recognizing “non-social stimuli” (in this case, flowers). But faces — faces they know.

If personality is a factor in face recognition, it also makes sense, then, that a 2011 study led by Davis found a link between social anxiety and poorer face-recognition skills. “It may be that the ability thrives with personality traits,” he tells The Cut. “But I think it’s more that the ability is made by personality.” It’s possible that a lifetime of avoiding eye contact means that shyer people simply get less practice at recognizing faces, as compared to their more sociable peers. Writing in The New Yorker in 2010, Sacks wondered about a link between his own shyness and his prosopagnosia:

Parties, even my own birthday parties, are a challenge. (More than once, Kate has asked my guests to wear name tags.) I have been accused of “absent-mindedness,” and no doubt this is true. But I think that a significant part of what is variously called my “shyness,” my “reclusiveness,” my “social ineptitude,” my “eccentricity,” even my “Asperger’s syndrome,” is a consequence and a misinterpretation of my difficulty recognizing faces.

And he also hinted that his own face blindness might’ve been inherited:

My mother … seemed almost pathologically shy. She had a small circle of intimates—family members and colleagues—and was very ill at ease in large gatherings. I cannot help wondering, in retrospect, if some of her “shyness” was due to a mild prosopagnosia.

Scientists who study face perception have long argued that faces are “special” to us. There is a region in the brain, after all — the fusiform face area — that is, some neuroscientists argue, specifically dedicated to face recognition. But what seems to be special in particular about the face? For most of us, it’s the eyes; this is what most of us tend to fixate on when trying to recall whether we’ve seen a face before. Eye-tracking studies on super-recognizers, on the other hand, are suggesting so far that their eyes focus somewhere in the center of the face, which perhaps allows them to take in and subsequently process the entire visage at once, rather than focusing on the face feature by feature.

But those with prosopagnosia do something rather interesting in studies testing their facial recognition: They avoid the eyes, preferring not to make eye contact for very long even with a picture of another person, an observation that seems to bolster Davis’s social-anxiety study. The causality here isn’t clear — maybe extroversion causes superpower-like facial-recognition ability, or perhaps it works the other way around. Either way, your skill at recognizing familiar faces, or placing an actor you just know you’ve seen somewhere before, seems to say more about your personality than you may have guessed.