On Twitter, Facebook and sometimes — horrifyingly — in real life, you may have noticed something this week: Suddenly, everyone you know is an expert in parenting, zoos, gorilla behavior, or, perhaps, all three at once.

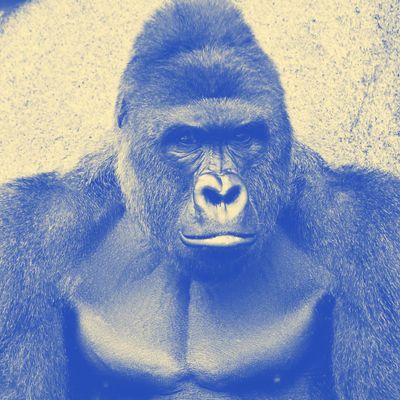

There are a few predictable stages to the freakout news cycle, and this — what psychologists might call overclaiming — appears to be one of them. This week, in the days following the sad death of Harambe the gorilla at the Cincinnati Zoo, chances are high that you’ve seen people you know — who never before showed much evidence of expertise in zoos or primates or parenting — acting a bit like experts on the relevant subject matter. And if you suspect that your friends and acquaintances who are noisiest about their expertise may in fact know the least about the subject at hand — well, you may be onto something.

The scientific literature on the overclaiming phenomenon is at once fascinating and frustrating, because it seems to happen so easily. For example, in an interview with Science of Us earlier this year, University of Chicago psychologist Nicholas Epley brought up a 2015 study published in Psychological Science, which demonstrated just how ready many of us are to believe we know more than we do about a given subject. First, the researchers — from Cornell and Tulane — primed some of their human guinea pigs into thinking they were pretty good at geography, by giving them an easy quiz. Next, though, things got trickier. The experimenters gave the study volunteers a second set of questions, this one listing American cities and asking how familiar they were with each one. The catch: Some of these cities were totally made up. (Wouldn’t you like to plan a trip this summer to Monroe, Montana? What about Lake Othello, Wisconsin?) Those who had taken the easy quiz were more likely to fall for this trick, telling the researchers that, why yes, they were indeed very familiar with Cashmere, Oregon.

What this suggests, the study authors argue, is that it doesn’t take much to nudge people into feeling like experts, which leads them to then overestimate their knowledge in some area. A quick scan of the headlines is likely even enough to do it, as Epley noted in January. As it happens, Cornell psychologist David Dunning is listed as an author on that Psychological Science report — he is the Dunning of the famous Dunning-Kruger effect, established in an influential 1990s study that found people with the least knowledge about a subject (say, for instance, grammar) often claim to know the most about it.

And the problem here, as Dunning and his co-authors write in the 2015 paper, is that if people feel as if they’re very knowledgeable about something, they’ll then be less inclined to try to learn more about it. “[A] tendency to overclaim may discourage individuals from educating themselves in precisely those areas in which they consider themselves knowledgeable and that may be important to them,” they argue. “In other words, overclaiming may hinder people from truly achieving a valuable level of genuine knowledge.” A rather similar thing happened earlier this year with the East Coast blizzard, and it will surely happen again the next time an exciting story hits during an otherwise slow news cycle. A word to the would-be wise: A little humility never hurts.