On Tuesday, while I was in the midst of a dumb evening of cheap reality television, Alton Sterling was busy getting killed. You know his story already. He was selling CDs, or he was selling cigarettes, or he was buying tea. As Claudia Rankine writes in Citizen: An American Lyric, “Each time it begins in the same way, it doesn’t begin the same way, each time it begins it’s the same.”

In a cocoon of oblivion, I only found out about Sterling’s death early the next morning on Twitter. “Video Shows Fatal Confrontation,” the headline read. Sounds about right.

I went about my day angry and hurt, but the point is, I went about it. I tweeted a thing or two. I wrote about beauty. I did my job. I went to bed. The next morning I woke to the news of Philando Castile.

This is an essay on being black and confused, and how to survive suffocating sadness.

The morning I heard about Castile, the slain 32-year-old black man who worked as a cafeteria supervisor at a Montessori school in Minnesota, I chose to watch tennis. I elected to watch Serena Williams demolish Elena Vesnina in 48 minutes, instead of watching the 10-minute Facebook Live video in which Castile squeezed his last breath as his blood gushed onto his seat, gurgled around his stomach, and flooded his lungs. There’s a song in The Wiz called “Don’t Nobody Bring Me No Bad News” — do you know it? I hummed it under my breath, hot and sticky with numbness, as I watched Serena whack the ball with targeted abandon: ace after ace after ace.

But later, of course, I watched the video.

I watched Castile die. I watched Diamond Reynolds, his fiancée, be the model bystander, because that’s the sort of thing you need to do when you are black, and in close proximity to police, and busy almost getting killed. She said “sir” to the man who had just shot her fiancé more times than I could count. Each time she said it, it latched onto my heart like a rusty pair of shackles strapping my legs. “You told him to get his ID, sir.” “Yes, I will sir, I’ll keep my hands where they are.” “You shot four bullets into him, sir.” “You told him to get it, sir!”

You want to know something about black sadness, black pain, black angst? It’s the resilience to remain calm when your protector, a police officer, becomes your predator. It’s when Reynolds, sobbing and overcome with grief, is comforted by her young daughter in the midst of a chaotic situation, unfathomable to bear. A child who has witnessed a murder. “It’s okay, Mommy, I’m right here with you,” her daughter said.

When I watched the video I was fine until I wasn’t. A hot, acidic bile cut through the fabric of my throat. I’m going to vomit, I thought, so I called in sick. Besides, the idea of writing about pretty little packages of makeup on a day like yesterday made me nauseous with disillusion.

I wanted to sleep, but I couldn’t. I checked Twitter. More information about Castile trickled through my feed. He was a good guy. He carried a gun. He had a permit. What did the NRA say about this man with a gun? Nothing. The Second Amendment is a right that chucks its meaning when your skin is black and not christened with the bulletproof cloak of privilege.

I logged onto Instagram and saw an H-list New York socialite — one who profited from and built a career on, among other things, the commodification of black music, black features, and black language — write “#AllLivesMatter.” In her comments, I wrote, “What the actual fuck” without a question mark.

I cut this discount, diet, budget Rita Ora to size on Twitter, and I am not ashamed to admit that it felt really good.

I tried to watch cable news, but cable news was preoccupied with Hillary Clinton and how she would not be charged by the FBI. Of all the things to care about that day, Hillary’s emails couldn’t even squat in the deepest corner of my mind.

I thought about the Kameelah Janan Rasheed exhibition I saw at Brooklyn’s Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts last year. “How to Suffer Politely (And Other Etiquette)” is what she called it. “Lower the Pitch of Your Suffering” she printed in black and shucked against a bright-yellow background.

I said “Fuck it” a few times, and really meant it.

My eye twitched uncontrollably and I consulted WebMD. “May be associated with fatigue, stress, or caffeine,” it read. Right.

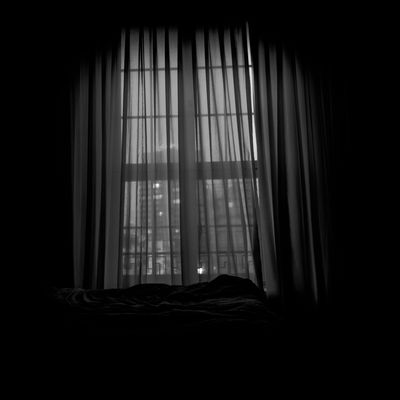

In the middle of this all, I ate so much and finished my copy of Citizen, a book whose weekend purchase could not have been more timely. As I read, “Appetite won’t attach you to anything no matter how depleted you feel,” I felt as if Rankine had written this especially for me, for this moment. I ate, talked to my mom, texted my friends, “Are you okay?” and tried to ignore the steaming cauldron of Twitter thumb thugs who called me racist because I snapped a photo from Rankine’s book. I clicked through several articles on Idris Elba because he contributed to a new interview, but mostly because he was shirtless and sexy as hell. And all the while I refused to go outside, because nothing felt safer than a couch, a TV, and the selective solitude of the internet, which could be turned off with just half a thought.

I watched protesters resolutely march down Fifth Avenue, and felt bad that I didn’t feel bad I wasn’t there. When that proved too much, I followed the hashtag #CarefreeBlackKids2k16, which was pointedly created for people who struggle to lift their heads under so much sorrow and which, in many ways, was forged for me. I tuned into Oprah’s soapy new show, Greenleaf, and for the first time all day I started to feel whole again. I ate a tub of Häagen-Dazs with zero regrets.

Before I went to bed last night, I roamed over to CNN for one last glimpse at the news. At a peaceful protest in Dallas, several police officers and civilians had been shot, and a few had been killed. On Twitter, giddy critics leaped at the opportunity to roll into my mentions. “What do you have to say for the police officers killed tonight?” asked someone who used an animal as their profile picture. “What do you have to say now?” said another.

On television, a black man spoke to Don Lemon: “I immediately went home. I didn’t want to get shot. This is crazy, Don.” And he also spoke to me.