Immediately, the prose in Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond feels new but deeply familiar — like the voice in your head but dialed just to the left. You are dropped into the book without your wits about you, and you may not totally recover them. It’s exhilarating. Mise-en-scène does not begin to describe it. Mise-en-brain?

The experience, for me, was a bit like reading a book of my own internal monologue, if I were a bit funnier and more brilliant, if I were both wilder and more attentive to the world. Isn’t this everyone’s ideal narrator? Wildly confident but also neurotic, holding forth on the state of her compost pile?

Pond’s narrator is a woman who lives a very small life in a very old cottage in Ireland. Hermetic is not quite the word for her life, as there are neighbors and a gentleman caller — who is not so much introduced as just there, occasionally, with an exciting lack of context — but there is a romanticized aloneness. Her life has the sort of tiny-house simplicity that a design blogger would jerk off to, but which the narrator smartly and swiftly undercuts (the thatch on the roof, it turns out, is not locally sourced, unless you consider pre-Brexit Turkey local).

This solitude offers the mental freedom to digress and to proclaim (“Oh Tomato Puree!”) and to spend pages on beautifully ludicrous digressions. Within these digressions are details, and idiosyncratic, almost-confessional meditations on those details that would put Knausgaard to shame. This is a woman at her most comfortable, her most confident.

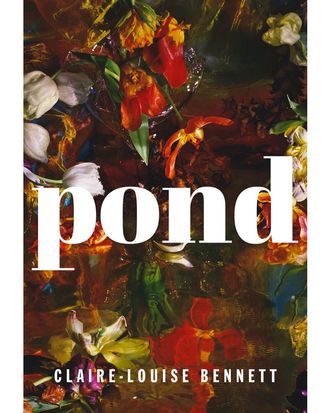

The book’s publication would be improbable (is it a novel? short stories? essays?) were it not already a runaway hit, first published by a small press in Dublin, and then in the U.K. by an even fancier indie press in London called, fittingly, Fitzcarraldo — journeying as small, weird books sometimes do, over mountains and then downstream. This is a writer’s dream, in a way: to write a perfect, seemingly unmarketable book, have a series of beautiful book covers, and then wind up published by Riverhead (the imprint that released the U.S. edition of Pond this summer, and which has, inarguably, the very best tote bags). There is not even a categorization of the book on the back of the hardcover-book jacket; no useful if reductive FICTION/WOMEN/PSYCHOLOGICAL to speak of, no marketing angle aside from a well-placed blurb from Colum McCann (a man!), who starts out by saying, “A touch of William Gaddis. A touch of Lydia Davis. A touch of Samuel Beckett. A touch of Edna O’Brien.”

Onboard, onboard, onboard, onboard, I say.

It is simply a book. A debut. A work of art! It feels, to me, if by nothing else but instinct, like a distinctly female consciousness, which makes the Knausgaard comparison that much more pointed. It is a short, concise, cutting book. It is 195 pages, not 3,600 pages, not six volumes. The experience of reading these books side by side, as I did inadvertently, is incomparable except for the thing that is most remarkable about them both: They offer, in different styles, and at different lengths, an almost-painful intimacy with the reader.

Is the human condition not, most of the time, each of us stuck in our subjectivity? Pond feels to me like subjectivity, captured on the page. There are clues that an entire life — a narrative! — is lived just offstage. There is a plot somewhere outside the margins, just hinted at. A failed academic career, a romantic relationship (one developing and echoes of one lost?), various reasons for being here, in this cottage, contemplating compost and stove-top dials. It is entirely disorienting, entirely like dropping into someone’s thoughts.

It is a portrait of a woman’s inner life, where she is arguably at her most free (which is not to say free!).

A few chapters in, I took a photo of the perfect cover and put it on Instagram — an act it was perhaps made for — thereby proclaiming myself only mildly exasperated by and totally in love with this book. “Same,” my friend Lydia wrote. I exhorted a few women writers to pick it up, too. It is a book that, like Knausgaard, I would not recommend to everyone, or not without knowing it might drive 70 percent of people crazy. I know not everyone would find the prospect of being almost-bored by a book exciting, to consider it a daring thing for a writer to write an entire feverish chapter about the broken dials on her stove top. Fair, I say. I think by the end it drove me crazy, too. Imagine what this writer could do with a plot, I did think. It isn’t fair, and I should confess I have the same blasphemous thoughts about Renata Adler. But if you are interested in the project of writing, especially of writing female consciousness, it is an exhilarating work. I adore this woman’s brain (I adore Karl Ove Knausgaard begrudgingly, carefully, with suspicion). I think someone should award her a great prize so that she can write us all something new.

I sat up straighter reading it, stowed it away in my (lesser, not-Riverhead) tote bag with affection before I left the house each day. I drove my son to day care looking forward to the half-hour or so of quiet I’d have to sit with this brilliant, exasperating woman’s brain. Weeks later, my son found it on my bedside table. “Your book!” he said. “I remember it!” The house is filled with books; filled, even with slim hardcover volumes of autobiographical fiction by women, but this one will stay with me the way the cover has stayed with my unbiased 2-year-old.