Of the many Trump-blasting retorts Hillary Clinton delivered during last night’s presidential debate, the one that drew that most gleeful response from the type-A women in my life was the one designed to address a persistent critique of Clinton — her so-called overpreparation — and rebrand it as a strength: “I think Donald just criticized me for preparing for this debate. And, yes, I did,” Clinton said, turning to look at him. “And you know what else I prepared for? I prepared to be president, and I think that’s a good thing.” Somewhere, fictional high-school honor-roll student Tracy Flick was beaming.

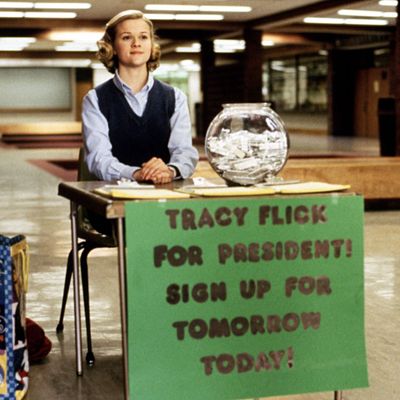

Tracy Flick, the teenage headband-wearing protagonist of 1999’s Election, remains the fictional character most frequently associated with Hillary Clinton — even though the movie is nearly as old as today’s youngest voters. Directed by Alexander Payne and based on a 1998 novel by Tom Perrotta, Election depicts a high-school civics teacher’s descent into madness as he tries to thwart a reviled overachiever’s ascent to the student-council presidency. Matthew Broderick, who earned infamy as high-school slacker icon Ferris Bueller, played the teacher, Jim McAllister. And in a performance that defined public perception of her for years, Reese Witherspoon played Tracy Flick, “the ambitious, cutthroat know-it-all who sits in the front row and raises her hand a little too often.” When McAllister realizes that Flick is running for student president uncontested, he recruits popular-but-ignorant jock Paul Metzler to run against her. As McAllister spirals into a full-blown midlife crisis marked by his psychosexual obsession with Flick, the tightly wound Tracy also unravels. At her nadir, Tracy tears down a wall of campaign posters. At his nadir, McAllister rigs the election against Tracy — and manipulates his announcement of the fraudulent results to maximize her humiliation.

Tracy Flick has long been viewed as an homage to Hillary in the ’90s — they have the same blonde bobs, jutting chins, and feminist gumption. (Tracy’s single mother has one hobby: writing letters to female leaders and political wives for advice on raising her daughter.) The comparison is so deeply ingrained that, when asked whether she would ever play Hillary, Reese Witherspoon said she already had — and that she discussed the role with Hillary when they met. Over the years, critics have debated the relative accuracies — and sexist cruelties — of likening Clinton to Flick. But when I rewatched the movie last week, the most blistering commentary wasn’t about Hillary so much as the people who hate her. Seventeen years ago, Election’s portrayal of a chronically emasculated teacher’s campaign to destroy his most talented female student was darkly comedic. Today, with a dick-obsessed demagogue unleashing vitriol toward the most ambitious woman in American history, Election is downright brutal.

Perrotta’s novel hit shelves shortly after the Lewinsky scandal broke — which means, though similarities between Tracy and Hillary were likely intentional, echoes of Monica Lewinsky may have been an eerie stroke of luck. If Hillary Clinton is Tracy Flick’s destiny, then Monica Lewinsky is her origin. At the beginning of the film version of Election, McAllister and Flick take turns describing the straight-A student in voice-overs. “Some people think I’m an overachiever, but I think they’re just jealous,” Tracy says as a series of clips show her starring in the school musical, leading the yearbook staff, and leading a litany of student clubs. Then McAllister interrupts: “There’s one more thing you should know about Tracy.” Cut to a middle-aged man growling straight to the camera: “Her pussy gets so wet, you can’t believe it.”

The middle-aged perv in question is McAllister’s best friend, a teacher named Novotny, who takes Tracy out to pizza, asks her if she’s lonely, and says he’s found her “attractive” since she was in the ninth grade. It’s to Payne’s credit that Tracy is far more than a two-dimensional victim — after Novotny lures the fatherless Tracy with every sleazy-older-guy cliché, she turns the tables, dumps him, and leaves him crying about love as he loses his job. McAllister’s anxiety about Tracy, then, is equal parts Hillary-hate and Monica-fear: He resents and is repulsed by her ambition, but he also harbors sexual fantasies about her and sees her as a dangerous temptress. She is, as the Atlantic’s Megan Garber once described, “manic pixie scheme girl,” simultaneously sexually repulsive and sexually irresistible to those who project their fears onto her.

Back when news of Monica’s affair with Bill Clinton broke, some observers sought to paint Monica as a precocious temptress by pointing to an affair she had (at age 19) with a married teacher from her high school. It’s almost incomprehensible to me that, in 1998, onlookers interpreted that affair as evidence of serial home-wrecking — when all I see, in 2016, is a young woman who fell into a series of unhealthy sexual power dynamics with men who were supposed to be her role models. Likewise, Tracy Flick’s primary offense is her ability to thrive despite various male authority figures’ best attempts to thwart her. The character never exactly comes across as a victim— nor does she seem to view herself that way — but in retrospect, I don’t think I was primed to see her that way until more recently. When I watched the movie in previous years, I responded to the comedic value of Reese Witherspoon’s tightly wound and grimly crazed performance. It wasn’t until this year that I picked up on the brief, but heartbreaking, moments depicting the idealistic teenager’s wounded confusion when she does everything she is supposed to do, but discovers that everyone hates her anyway.

If my memory didn’t fully do justice to Election’s portrayal of chauvinism, then it completely erased the film’s portrayal of classism. Enduring a classroom snub from Mr. McAllister, Tracy’s face registers disappointment — until she comforts herself with a condescending rant. “Now that I have more life experience, I feel sorry for Mr. McAllister,” she reflects in a smug voice-over. “I mean, anyone who’s stuck in the same little room, wearing the same stupid clothes, saying the exact same things year after year for all of his life, while his students go on to good colleges and move to big cities and do great things and make loads of money — he’s gotta be at least a little jealous. It’s like my mom says, the weak are always trying to sabotage the strong.” This is, essentially, a very rude and ham-fisted attempt to articulate the kind of anxieties that analysts cite to explain Trump’s rise. McAllister is afraid that “people like Tracy” will rise up to take over the Establishment — while people like himself toil in obscurity. He wouldn’t feel bad about his place in the hierarchy, were it not for people whom he views as less-deserving displacing him — people like Tracy, the only daughter of a single mother, who comes to symbolize female ambition. Likewise, Trump and his followers worry about ascendant outsiders: immigrants, competing nations, women who “play the woman card.”

With Tracy Flick’s problems providing such an easy foil for Hillary’s, it’s tempting to draw parallels between Donald Trump and ignorant jock Paul Metzler. (“I know what it is to win,” Paul announces, to thunderous applause, at a rally in Carver High School’s gymnasium.) But I’d actually argue that the most Trumpian character in Election is thrilling, magnetic anti-heroine Tammy Metzler, who launches a nihilistic presidential campaign solely to antagonize her brother, who unknowingly stole Tammy’s girlfriend. “She’s not qualified! She’s a sophomore!” Tracy screams when Tammy throws her hat in the ring, expressing a kind of indignant disbelief that the political Establishment still routinely expresses about Trump. After Paul delivers his campaign speech about winning — and Tracy delivers a traditional stump speech quoting Thoreau — Tammy takes the dais and, after enduring a wave of taunts, delivers this barn-burner:

Who cares about this stupid election? We all know it doesn’t matter who gets elected president of Carver. Do you really think it’s gonna change anything around her? Make one single person smarter or happier or nicer? The only person it does matter to is the one who gets elected. The same pathetic charade happens every year and everyone makes the same pathetic promises just so they can put it on their transcripts. So vote for me, because I don’t even want to go to college! I don’t care! I don’t even want to be president. The only promise I’ll make is that as president I’ll immediately dismantle the student government so that none of us will ever have to sit through one of these stupid assemblies again!

As Carver High erupts with cheers, Tammy shouts: “Or don’t vote for me! Who cares? Don’t vote at all!” This, of course, bears no resemblance to the actual Donald Trump, who cares deeply about how others regard him, how they vote, and whom they like. But her nihilistic exasperation seems to share DNA with various Trump-adjacent panics and pessimisms, when a candidate’s ability to ascend to the presidency seems to have little correlation with his desire to execute presidential tasks — but a lot to do with general desires to dismantle a number of social and political conventions, institutions, and practices.

I imagine that how anyone feels about the end of Election will be a Rorschach blot reflecting how you feel about feminism, men’s rights, and who is entitled to what. After some mildly dirty maneuvers, Tracy wins the election. But when Mr. McAllister sees her elated reaction to discovering her win before it has been officially sanctioned, he is so disgusted that he snaps. As Reese Witherspoon bounces around in an over-the-top display of teen-girl giddiness, Broderick intones: “The sight of Tracy at that moment affected me in a way I can’t fully explain. Part of it was that she was spying. But mostly it was her face.” As in, the face of a happy girl who is proud of an accomplishment earned against the odds. “Who knew how high she would climb in life? How many people would suffer because of her? I had to stop her.” What follows is a comedy of errors that, I expect, is not quite as funny now as it was 17 years ago. McAllister rigs the election; Tracy stands up to accept her win; McAllister announces a different winner; and the teen girl is, for the second time in her life, undermined by a lecherous male authority figure who abuses her power to take away what should be hers — her academic life, her love life, her extracurricular accomplishments, her sexuality, her self-esteem — and hands it to some undeserving guy who thinks about his penis a lot. It’s very bleak.

To be clear, Election is still a sharp and entertaining movie, and Mr. McAllister was clearly designed as a pathetic anti-hero whose fragile masculinity was a source of humor. But I can’t shake the feeling that, in an era of alt-right toxicity and Gamergate attacks, McAllister’s entertainment value has changed. In the late ’90s, his powerless frustrations were funny and a little bit sad. But today, when groups of strangers routinely channel their malevolence into coordinated attacks on random women whose so-called crimes are roughly the same as Tracy’s — annoying others simply by existing and striving and refusing to back down from their goals — the whole affair is much darker. McAllister is no longer a powerless twerp with benignly misogynist impulses — he’s a precursor to the type of hatred that would one day drive chanting crowds and respected officials to call for the imprisonment (or even execution) of Hillary Clinton. As is also the case with Donald Trump, that which seemed laughable a few years ago is now alarmingly, gruesomely real.