In her book Nonstop Metropolis: A New York City Atlas, Rebecca Solnit posits this question: What if New York City’s subway map paid homage to the city’s great women? “Statues of women are not uncommon, but they’re allegories and nobodies,” she writes. “I can’t imagine how I might have conceived of myself and my possibilities if, in my formative years, I had moved through a city where most things were named after women.”

The same frustration applies to art history, as made clear in the exhibition Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s, on view at the Photographers’ Gallery in London through January 8. Here, 48 international female artists (celebrated across 150 works from the Verbund Collection in Vienna) refute female invisibility and omission with a blend of originality and strength, if underpinned by exaggeration.

Photographs, collages, and filmed performances by a wide swath of international figures throw a wrench into conventional perceptions of womanhood. The collection challenges the confines of the domestic sphere, the objectification of the female body, and the infuriating typologies of women recklessly and casually propagated in the media and in public discourse.

The artists mobilize their work as radical confrontation: questioning gender expectations, binary roles, and sexual politics, thus reinforcing their own agency. These artists sought to overhaul the prevailing iconography of women as passive or as muses to men — often by powerfully, and sometimes quite disturbingly, utilizing their own bodies to highlight sexism. In doing so, they created an assertive, appropriately complex alternative female identity.

The examples are manifold. Take Judy Chicago’s Red Flag, a photo-lithograph in extreme close-up of a woman pulling out a reddened tampon from between her legs, derived from her installation Menstruation Bathroom. Or the series of photographs by Karin Mack of a lady cheerfully holding a jar that are progressively ripped to shreds, leaving only a pockmarked and pinned wall. Or Birgit Jürgenssen, who hilariously photographs herself sporting a hybrid 3-D apron/mobile stove with a roast poking out of the oven just above her prim T-straps.

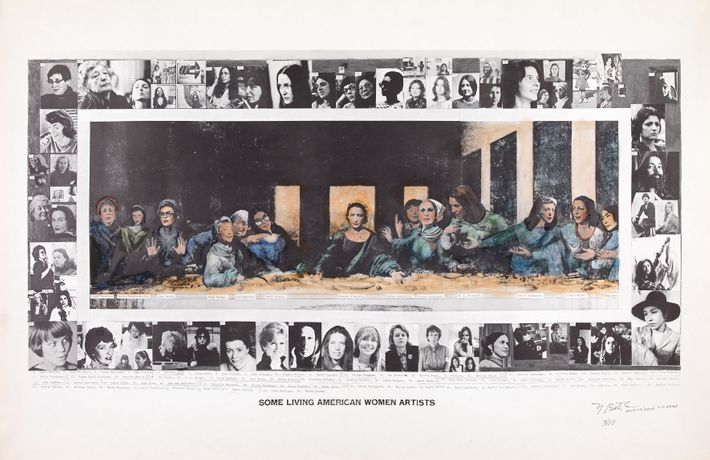

Mary Beth Edelson’s empowered reimagining of The Last Supper overwrites the art historical masterpiece with an all-female cast that would be the coolest girl gang: Georgia O’Keefe with Louise Bourgeois, Yoko Ono, Nancy Graves, Lynda Benglis, and many others. Martha Wilson’s A Portfolio of Models presents six ill-suited templates of womanhood, which include the housewife (“she is intelligent, but she has convinced herself she is fulfilled”), the professional (“she plays down her competence to get along”), and the lesbian (“the goddess was invented by the men on Madison Avenue”).

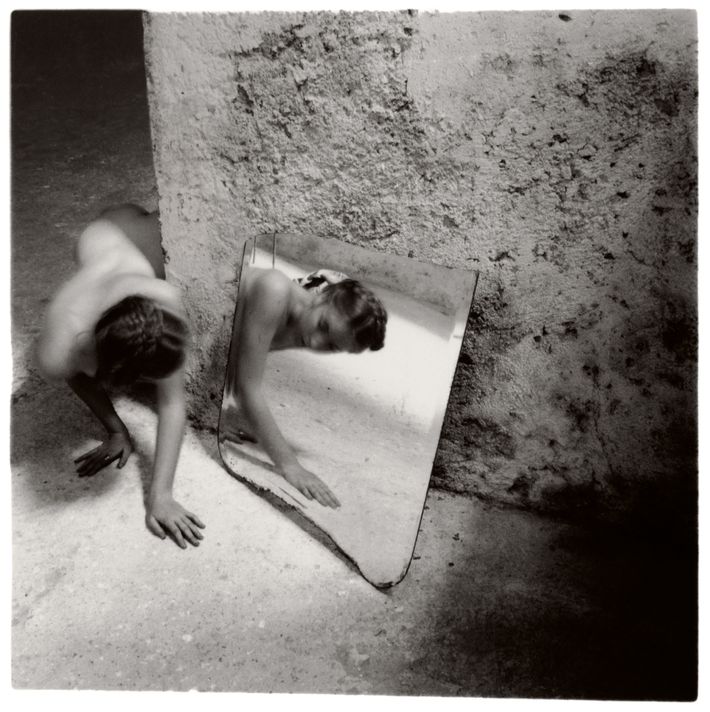

There’s a gleeful “cunt coloring book” from 1975 with drawings by Tee Corinne. Francesca Woodman’s photographs feel uneasy, on the brink of danger: In one image, she prowls on her knees before a mirror in an abandoned space. In another, three naked women facelessly hold up identical portraits to hide their features.

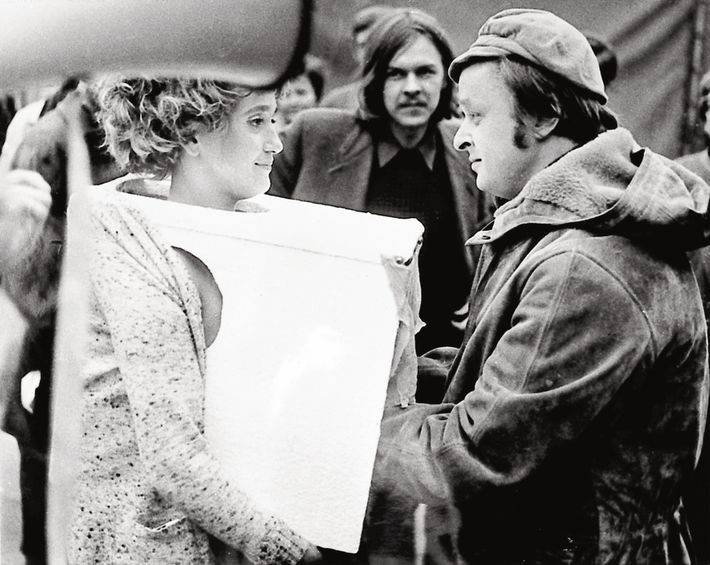

One of the most devastating works is Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz’s In Mourning and In Rage, a filmed public performance prompted by a Los Angeles Times report about a serial killer who raped and murdered ten women between 1977 and 1979. Disgusted by the press coverage and galled by political powerlessness, the two artists organized a public rite on the steps of City Hall in Los Angeles, vocalizing heartache and fury. Some 70 women took to the microphone to share chilling statistics about abuse and assault, each proclaiming: “I am here for the 10 women who have been raped and strangled between October 18 and November 29.” The thing is: If this happened yesterday, it would be just as current.

What makes this exhibition alarmingly powerful, in fact, is that the works are as resonant today as they were then: The legacy is unresolved, the struggle is still on our doorstep. Journalist Ginia Bellafante recently wondered in the New York Times: “Misogyny Is Back. Did It Ever Really Go Away?” This show — though funny, smart, and empowering — is yet another indication that it hasn’t.

Francesca Woodman, Self-deciet #1, Rome, Italy, 1978/1979.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled (Lucy), 1975/2001.

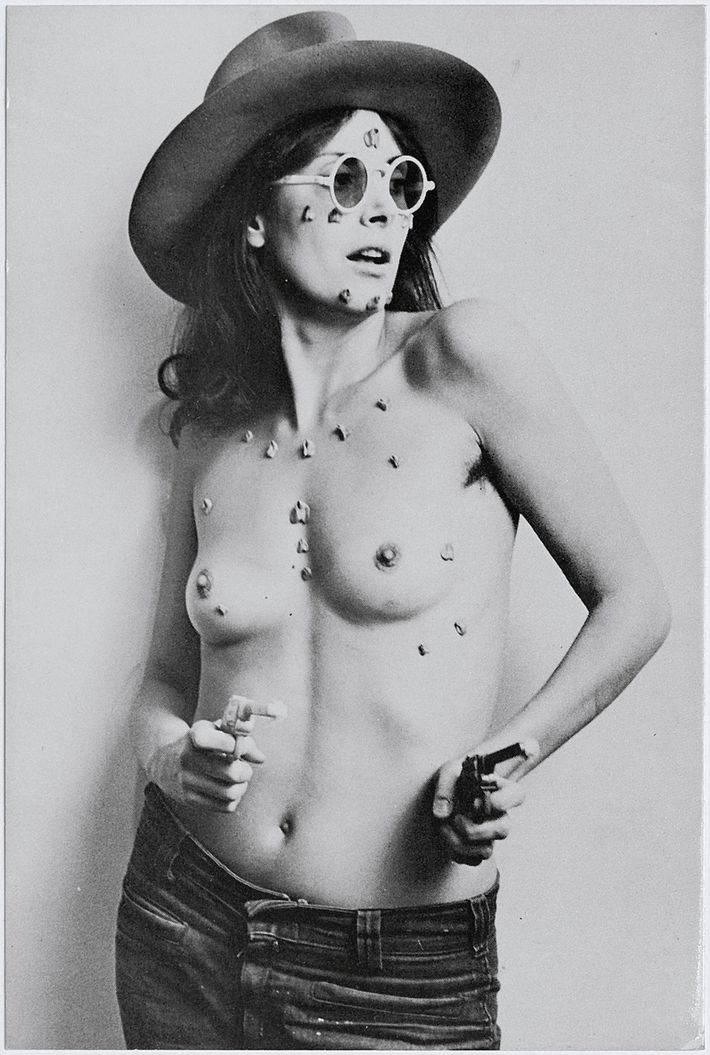

Hannah Wilke, S.O.S. Starification Object Series. One of 36 playing cards from mastication box, 1975. Postcard. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles.

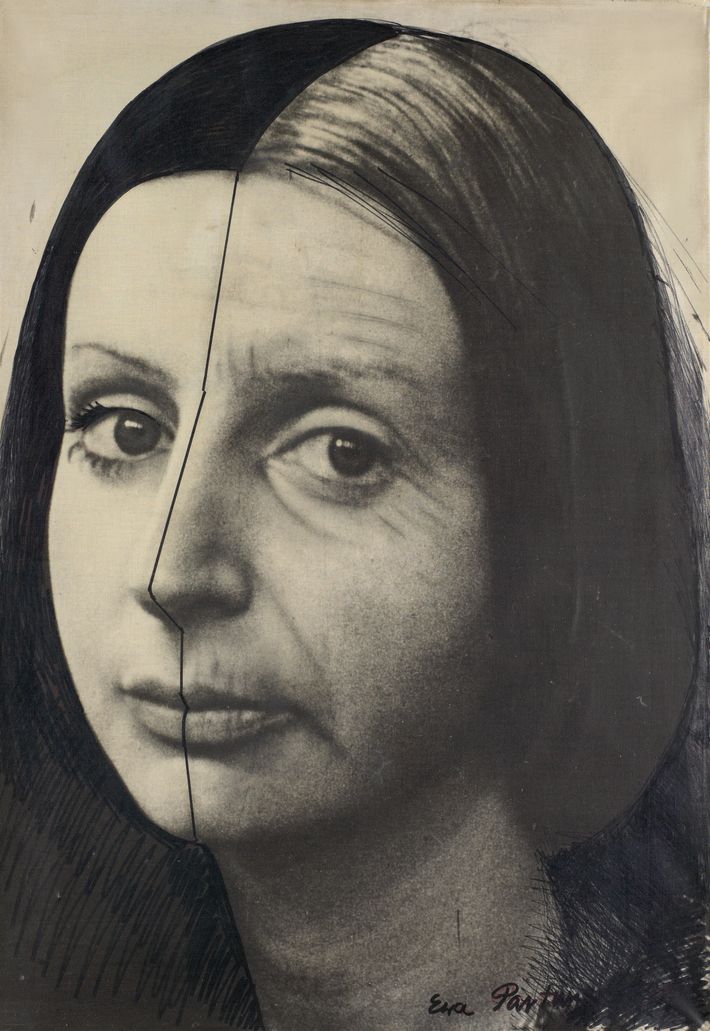

Ewa Partum, Change, 1974.

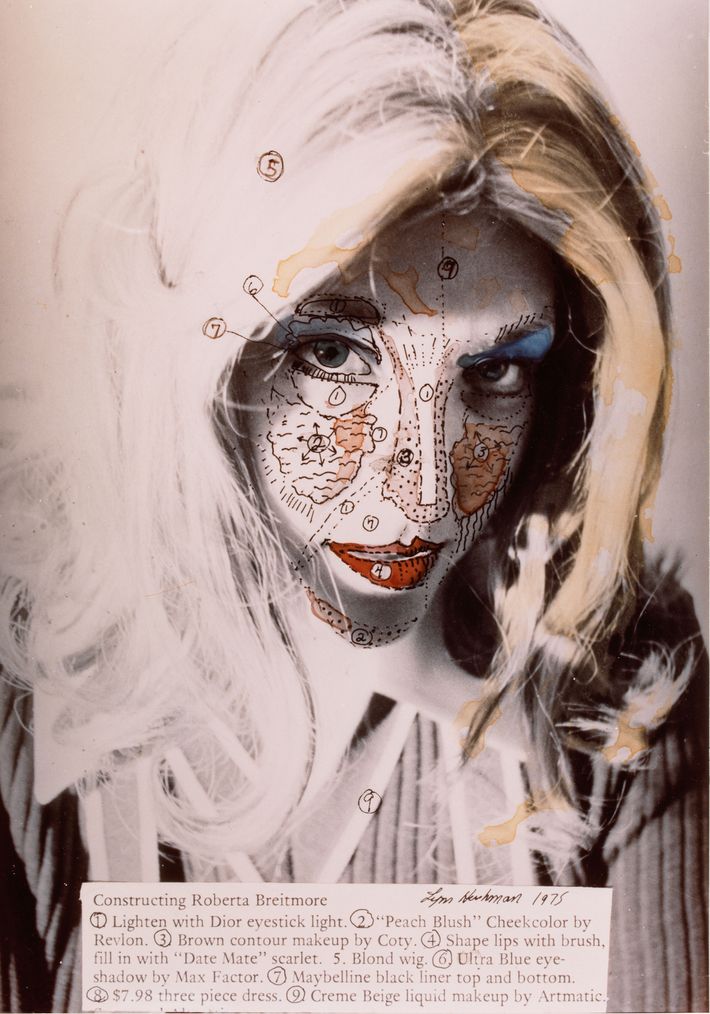

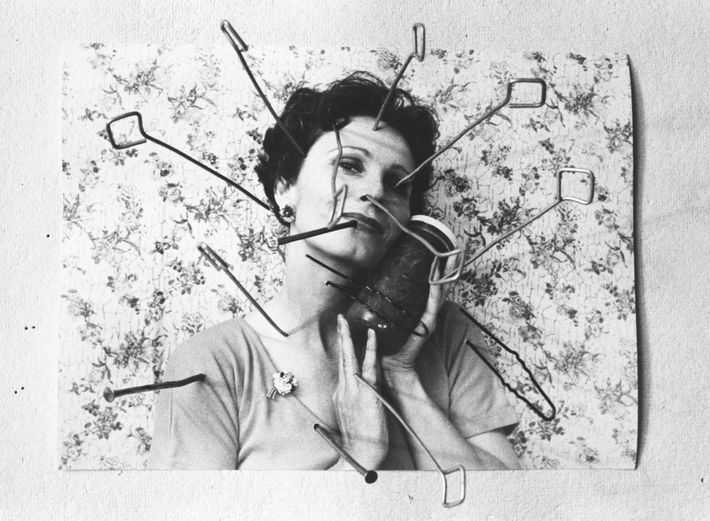

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Roberta Construction Chart #1, 1975.

Kerin Mack, Zerstorung einer Illusion, 1977.

Renate Eisenegger, Hochhaus (Nr. 1), 1974.

Valie Export, Tapp und Tastkino, 1968.

Mary Beth Edelson, Some Living American Women Artists/Last Supper, 1972.