It’s fitting that — on the eve of the first

presidential election in which we can vote for a major-party female candidate — the power of the female vote has been made triumphantly clear. If only women went to the polls next week, they’d turn the Election Night map almost entirely blue, and sweep Hillary Clinton into office with a landslide victory. Of course, this election has also been a stark reminder of how much is at stake, and how threatening women’s voices can still seem: Consider the Trump supporters tweeting pleas to repeal the 19th Amendment. That’s why the Cut is taking this moment to talk with the descendants of suffragists about their ancestors, their fight, and the 2016 election.

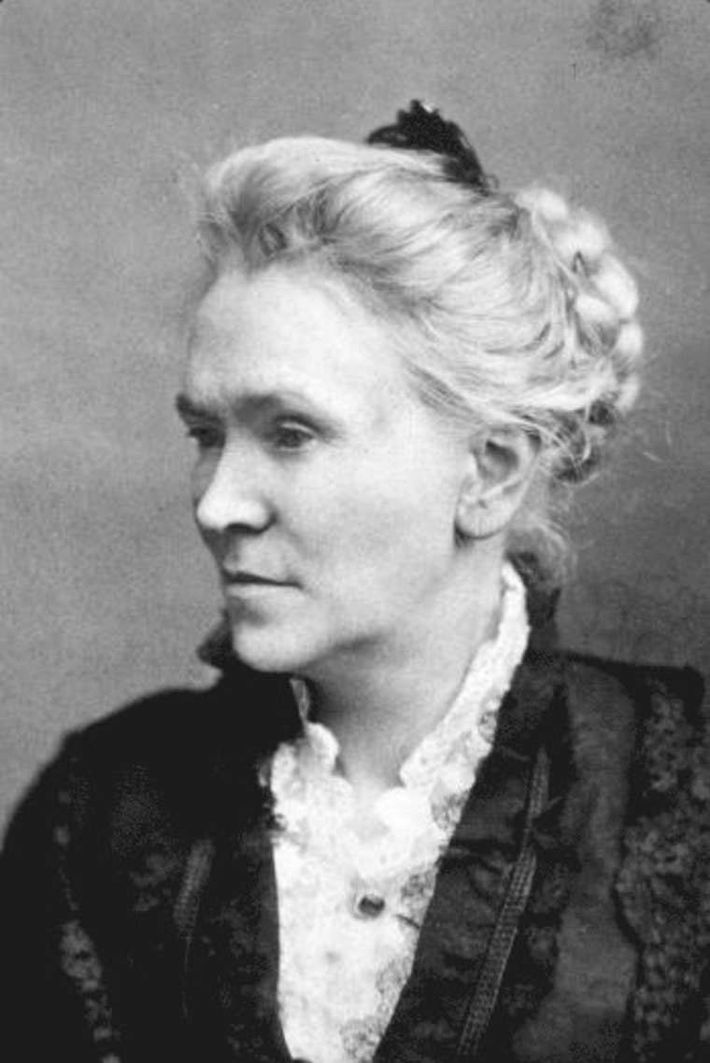

Florence Brooks Whitehouse

1869–1945

Whitehouse was a novelist and mother of three when she took up the suffrage cause in her mid-40s. Considered radical by her more conservative peers at the Maine Woman Suffrage Association, she fought with Alice Paul and Lucy Burns for a constitutional amendment and campaigned against Woodrow Wilson in his 1916 re-election bid.

Anne Gass, 57, great-granddaughter:

When I was about 40, I started reading her papers at the Maine Historical Society, and there was correspondence from Lucy Burns, co-founder of the National Woman’s Party, asking Florence to come and picket in D.C. And then I found an urgent telegram sent at five o’clock in the morning saying, Give publicity to the fact that all these women have been arrested and detained in Occoquan prison. These letters were clearly collegial. The writers addressed Whitehouse as an equal. It was clear that she’d been substantively involved in a way I’d never known, and at that point I was hooked.

Later, when I went looking for mention of her in Maine’s scant suffrage histories, I was frustrated to find she was barely mentioned. When she did appear she was presented as a fringe figure, causing more trouble than contributing solutions, when in fact she was one of Maine’s most effective suffrage leaders. As my research continued, I realized she was written out of Maine suffrage history by her more conservative peers. I became determined to ensure that she got the credit she deserved — this resulted in my book about her and her induction into Maine Women’s Hall of Fame.

Later on, I came across this poem that she’d written and recited to the judiciary committee of the Maine legislature in 1917. To me, it was her manifesto:

I have no quarrel with you; but I stand

For the clear right to hold my life my own;

The clean, clear right. To mould it as I will,

Not as you will, with or apart from you;

To make of it a thing of brain and blood,

Of tangible substance and of turbulent thought.

No thin gray shadow of the life of man.

Your love, perchance, may set a crown upon it;

But I may crown myself in other ways.

As you have done who are one flesh with me.

I have no quarrel with you — but henceforth,

This you must know; the world is mine, as yours,

The pulsing strength and passion and heart of it;

The work I set my hand to, women’s work,

Because I set my hand to it.

When I read that poem, my spine tingled. She had these bright, penetrating blue eyes and I could see her standing in front of the committee and looking each and every man in the eye and saying, “The world is mine.”

I think it is amazing that it’s taken this long, and amazing that we finally are able to vote for a woman as a major-political-party candidate. I’m a Hillary supporter not just because she’s a woman, but because I think she’s by far the best candidate. One of the complaints against Hillary is that she’s ambitious — I mean, really, why is that a bad thing in a woman? Still … today?

Elizabeth Green Kalb

ca. 1895–1974

Kalb, a member of the National Woman’s Party, participated in the U.S. Capitol picket and was arrested during a demonstration in January 1919 and sentenced to five days in jail.

Shirley Marshall, 59, surrogate granddaughter:

I knew her when I was a little girl. She was retired and living on a nearby farm in Virginia. I do remember it was said to me that she was a suffragist and it felt important — she fought in a war. She came to life for me when I was reading her letters. I knew this person as this lovely, sweet little old lady, and here are these letters about her literally on the front line of this radical movement, picketing the White House, getting arrested.

Because it was during wartime, the picketing of the White House was considered treason. You are fighting the government during a time of war? This wasn’t a minor case of “women behaving badly.” It was thought that they were really being inappropriate. To do that at the White House? That was radical.

I think she was arrested for five days and then released. She had the flu. They hurriedly took her home because they didn’t want her to die there because that would be really bad, politically. The 1919 flu epidemic was serious. So she might have actually been very sick, but she got through it, and her mother, who was also very involved, was able to join her in D.C. There’s a picture of them with Alice Paul right after the big vote. And then starting in 1921 they did a huge cross-country trip to California. They got involved in Indian rights. Wherever they lived, they got involved in what was going on.

I think Elizabeth would be turning in her grave over this election. The sheer incivility of the process. It’s one thing to sit and debate your policies and what you bring to the table and your vision and all that, but to sit and have these impossible arguments over nothing.

I lived in Afghanistan for a year, and I talked to some of the young women there who had been taken to D.C. to see how “wonderful” U.S. democracy is, and they kept saying, “Where are the women?” And it’s like, “There weren’t any, actually.” And then they went to Finland and it’s like 50 percent women in government …

If you don’t understand what your history is, you don’t understand that you have to fight for things. There had been 70 years of brave, selfless women fighting to give us the right to vote. People forget you have to keep that fight going. There’s more to be done. Someone needs to keep fighting and passing that spirit on.

Edna Kearns

1882–1934

Kearns edited suffrage news for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, but she is best known for the “Spirit of 1776” campaign wagon, which she rode from Manhattan to Long Island in 1913 to promote women’s suffrage.

Marguerite Kearns, 73, granddaughter:

Edna is my mother’s mother. Mom was 13 or 14 years old when she passed, but my maternal grandfather lived to his 90s. So my grandmother was very much a part of our lives even though she had been gone for quite a while. The presence of my grandmother was manifested by the suffrage campaign wagon that was in my grandfather’s garage. It’s now in the New York State Museum where it will be on exhibit in 2017. Every summer my grandfather pulled it out into the driveway and we all sat in it in our best summer clothes and my mother took photographs of us.

We know a lot about the movement’s leaders in New York State: lots about Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage … But the grassroots activists mattered, too, and that’s what this wagon is representative of: the tens of thousands of women that it took. My mother said, “Oh your grandmother did something very important. She helped American women win the right to vote.” And so I was convinced that at some point, the teachers in elementary would talk about this and I — this little, shy, wimpy person — would raise my hand and I would be in the spotlight and I would tell everybody about my grandmother. Of course, as we know, that daydream never happened because it was never considered important.

My grandfather marched in suffrage parades in New York City and Washington, D.C., too. They were Quakers and there is a Quaker tradition of equality of all people, men and women. I think she just fell in love with him because he basically said to her, “Be who you are, realize your dream.” He wanted her to be happy and she wanted to be an activist. He supported her thoroughly. When she went away to conferences and conventions, he was at home answering the phone and doing the support work. He’s a really sweet man.

Edna died of breast cancer. She treated herself with food. She put herself on a diet and she lived longer than they ever predicted. She went full-on organic and this was in the ’30s! No one wanted to talk about her when I was growing up. It was too devastating; they adored her. Finally, I said to my mother, “Don’t give me any more tea towels, I don’t want any blenders. I want to know about my grandmother.” I demanded that it was my birthright. Once she started, it just came pouring out. I interviewed her for years. We worked from 1982 to 1989: interviews and visits to relatives and collection of documents.

My mother was born in November 1920, right when American women were first able to vote through the 19th Amendment. In my mother’s entire life, American women could vote — but just barely.

Elisabeth Freeman

1876–1942

On a trip to England, where she was born, Freeman “saw a big burly policeman beating up on a woman, and I ran to help her, and we were both arrested. I found out in jail what cause we were fighting for.” She was known for her media stunts, improvised public speeches (at the cinema, at a boxing match), and involvement with several suffrage groups.

Peg Johnston, 68, great-niece:

Elisabeth’s claim to fame was being bold and fearless. She did these really incredible physical things, like walking from New York to Washington in the winter. She didn’t really write that much, but she had this relentless love for engaging in stunts. Hers, like the Yippies in the ’70s, was a more theatrical kind of resistance or “protest.” There was this idea of getting yourself out there, getting on the news. Except instead of TV news it was newspapers, and in those days there were like 60 or something in New York City — and she got in a lot of them. She made friends with reporters and they would take her picture. There was one exchange she had during one of her little jaunts to Boston where the person she was working for at Woman’s Journal said, “Be sure that they can see your newspaper bag that says Woman’s Journal and release this carrier pigeon and get a good picture,” and she did and there’s a picture of it. They really thought about the whole piece: what they wanted to achieve, how to brand themselves. Another thing that I remember is they went to Wall Street to hand out newspapers and they created a gauntlet of young women in white. These women in white dominated the space and made it so that all the working guys had to pass through them.

My mother told me that she’d said she couldn’t get pregnant, and although she had many offers she didn’t think it was fair to get married if she couldn’t have kids. I don’t think she was a lesbian; my sense is that her passion went into social justice. They were orgasmic about their movement and their work. Who needs sex when you have that going on?

Elisabeth was sent in by the NAACP to investigate this lynching in Waco. She happened to be close by, and they were very impressed with her and so they sent her. “She could talk the brass ear off a tin monkey,” people said. She was the white woman who could talk to black audiences. She was British-born but came here as a child, so I think she had less craziness about race. But I think it caused a rift with her suffrage work. She kept some correspondence from the Columbus branch of the NAACP to the Franklin County Woman’s Suffrage Association that basically said, “We’d love to support you in your suffrage cause but you have to support us. It doesn’t do us any good if we don’t support each other’s rights.” She kept that letter so clearly she was in support of that. I do think that she experienced discrimination. After that, she never worked for a suffrage organization again. After that, she got in with the lefties. She started working for the radical-peace people. I’m pretty sure she was disappointed and disillusioned by the suffrage folks.

This election season has been anxiety-producing to say the least. The assault on minorities, the xenophobia, does not seem very different from Elisabeth’s time. The election itself has revealed so much about sexism and racism that it feels like a turning point for our country.

Ida B. Wells

1862–1931

Wells, one of the few African-American women included in the fight for women’s suffrage, was also known for her anti-lynching crusades. She was radicalized in 1884, when she was thrown out of the first-class train cabin she had paid for. As she was being forcibly removed from the train, she bit one of the male officers. She was a founding member of the NAACP.

Alfreda Duster Ferrell, 82, granddaughter:

She was born a slave just before emancipation in 1863. Her father was the son of the master and her mom was the cook. After the Civil War, he became a carpenter and he made sure that his kids knew how to read and write. Her father and all of his friends would get together and read the newspaper and talk about what was going on and what could be done and so forth. Ida came up in that atmosphere. She grew up listening and understanding politics and society.

She was, as far as I know, one of very few African-American women who went into education and politics and the law and women’s suffrage. The women’s suffrage movement wasn’t very accommodating to African-Americans, but she was a friend of Susan B. Anthony. Susan said that she should not get married because she was such a powerful leader that she didn’t have time for that plus a husband. But she did anyway.

You cannot be in this country and not be politically or socially active with all of the prejudice here. You have to do something. My freshman year at the University of Michigan, the student council decided that they were going to prove that there was prejudice on campus. So I went to the Michigan Union, where women were not allowed to enter by the front door. I went and asked for an application to work there. They told me that they didn’t have anything. Then they sent in this white girl behind me and they said, “Okay, here’s an application, fill it out.” College is a microcosm of society.

When Obama was elected, I was elated, but I was also holding my breath because it’s one thing to have the first black president — but it’s another thing to have the people in power who are not going to let him do his job. Same with Clinton. I would love to see her as president, but she faces such prejudice. And I’m speaking as a female, not as an African-American. There’s almost more prejudice against her as female than there was against him for being black, or just as much.

Rose Schneiderman

1882–1972

Schneiderman is perhaps best known for her saying “The woman worker needs bread, but she needs roses too” — meaning women are full citizens who deserve both access to basic human rights but also education, recreation, and professional networks. Her organizing helped pave the way for a general strike by garment workers (mostly young Jewish women), and she later became the only woman on FDR’s National Recovery Administration Labor Advisory Board.

Annie Valliere, 60, grandniece:

She was cute but she was scary. I found her adorable, even as a little kid. She was tiny — no taller than four-six at her top height, a tough little lady. But there was a reason she developed that hardness. Somehow I didn’t catch much about her past until I was older. I realized she had done a lot of things to help women, and then I began to read about her, even though it was hard to find her in books.

She was a socialist and became a very active member of the Democratic Party, but still had socialist leanings. At least publically she was very feminine. She wore pearls, she dressed up in traditional feminine clothing; I think that’s how she wanted people to see her, kind of like Frances Perkins, who always presented herself in a motherly kind of way. Even as a little old lady, she had her little heels on — you know those special old-lady heels — lipstick that wasn’t quite on her lips, and, of course, pearls. Some other suffragists might have been frustrated with that, but she needed to do it. She didn’t marry, and she didn’t have kids. From what I know, she didn’t have any relationships with any men. She had what appears to have been an intimate, romantic relationship with a woman named Maud Swartz, who was involved with the Women’s Trade Union League. She died in the ’30s of a heart problem. They were very clearly close and spent a lot of time together, traveled together. They went together to visit FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt.

I’m proud to vote for a woman. I think that all of these women, not just Rose, fought for so many years for suffrage and also had visions of universal health care and all kinds of things that we still don’t have. Hillary represents how far we’ve come.

Rose was one of the first women to run for a national position; she ran to be a senator of New York in 1920 and it was under the Labor Party, labor activists. She didn’t get many votes and also, by doing that, she alienated some people. She died when I was 18. It wasn’t widely publicized. A lot of people didn’t know who she was. If she had died now, I think more people would be there, you know what I’m saying?

Susan B. Anthony

1820–1906

Perhaps the most celebrated member of the suffrage movement, Anthony served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, which she founded with Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She was regularly arrested for her protests, most notably when she illegally voted in a presidential election.

Susan Whiting, 60, cousin:

One thing that has always resonated with me is that it took a lifetime of work and negotiation. If you really look at all the collaboration and negotiation and activism that was required to do something that so many people disagreed with, to believe you were right, and to go through that for so many years, to take the long view . ..that’s a very impressive quality, I think, especially given the time period and how information moved. She had to work against so many odds. In life, it’s reminded me that the things I’ve thought were perhaps really difficult, yes, they were, but they weren’t ever as hard as this. The idea of how independent they were, and how self-sufficient and motivated and directed. There’s one quote that I love: “Forget conventionalisms; forget what the world thinks of you stepping out of your place; think your best thoughts, speak your best words, work your best work, looking to your own conscience for approval.”

I will say that I have a fairly independent view for each election, and that’s as much as I’ll say. My view on this election is actually very similar to my view about women in business, which is that I look forward to the day when the conversation is not about there’s a woman on the board or at this role or whatever, that we don’t actually discuss that, that it’s men and women working together, and it’s the normal course of events. It will be the normal course of events to have a woman be president. And I really think that’s an incredible accomplishment for the country. I think it’s wonderful that we’re getting to a place where your gender doesn’t determine who runs for the office, and that more and more men and women will continue to run for office — on both sides of the aisle.

Harriet Tubman

ca. 1820–1913

Tubman was, of course, primarily an abolitionist, but a number of her supporters during the Underground Railroad years were also involved in the women’s-rights movement. She later gave speeches about women’s suffrage, focusing on advancing the rights of African-American women.

Michele Jones Galvin, 62, great-great-great grandniece:

In the fourth grade, I had an opportunity to do a report on someone that I admired. My choices were Harriet Tubman or Sidney Poitier. Being the smitten young girl, I chose Sidney. Years later, I realized that I squandered an opportunity to introduce my classmates and teacher to my relative, Harriet Tubman, the greatest conductor of the Underground Railroad and the Moses of her people. I did not truly understand her importance to the family and the country until I was older.

So much more research needs to be done to study the socioeconomic and race politics of the women’s-right-to-vote movement in this country. A professor of mine once said that in order to understand a person’s politics and views you must understand the historical era in which he or she lived. Aunt Harriet was not a suffragist as we understand, historically, a suffragist to be. African-American women were not in numbers made visible or included in the overt, national women’s-rights movement. There may have been some African-American women — Sojourner Truth comes to mind — but white and African-American women were not marching and politicking shoulder to shoulder. I believe that Aunt Harriet understood the politics of her day. She was not personally excluded from the movement. I believe that the leaders of the movement during that era had to calculate the political capital of including African-American women. But did Aunt Harriet want women to have the right to vote? The answer is yes.

It is reported that by 1919, there were 300,000 African-American women in the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). The NACWC was instrumental in the late 1800s and early 1900s in putting the voice and force of African-American women behind uplifting their people, fighting against segregation, ensuring equality, fighting against lynching and injustice, and supporting women’s right to vote. It should be remembered that Aunt Harriet’s mission was to abolish the slavery of African-descent peoples, and fight for their civil and human rights. She was an abolitionist, liberator, and humanitarian. That was her cause. In many ways, we are still fighting for those rights, if not by law but in practice. I believe Aunt Harriet would be called to action today by the Black Lives Matter movement, mass incarceration, human trafficking, and the state of affairs of public education.

In my personal experience, growing up in the 1970s, as women continued to fight for rights in employment, equal pay, and health care, I did not find that the movement embraced me or other women of color. That may be changing now with the nomination of the first woman running for president of the United States. In my humble opinion, this run for the election of the first woman president is very significant. The question that should be asked is, to whom it is significant? The folks that came out in droves for Obama, do they feel this election speaks to them personally, economically, and historically — whites, blacks, other racial groups, men and women, old, young, working, unemployed, educated, and less educated? I imagine that the Clinton camp hopes so. We will see on Election Day. I believe the key is inclusion in politics and practice.

Catherine Flanagan

1888–1927

Flanagan was a little-known suffragist who picketed outside the White House and was arrested and sentenced to 60 days in the Occoquan Workhouse in the summer of 1917.

Patsy McDonald, 61, granddaughter:

My mother was born in 1924 and my grandmother died in 1927, so Mom didn’t have any personal memories of her. The women in our family were very proud that she had gone to jail, but they really didn’t know the particulars. I started really doing the research after my daughters were born — that’s when I realized that she was secretary to the National Woman’s Party. She was arrested in 1917, and 1917 was the beginning of the Silent Sentinels outside the White House. In Jailed for Freedom, they quote her a lot and tell how she was attacked by mobs of sailors. She was holding the banners so tight with her hands that her nails cut into her palm, so she must have been very brave.

In the image of her being arrested, she looks really scared. I think there were five other women arrested at the same time. They were told to pay a fine, they refused to pay the fine, and they immediately took them to Occoquan, which was not very nice. I think it was three months. Later it was found that that confinement was unconstitutional because they had been arrested in the District of Columbia [and then sent outside the city to serve their sentences], so later when Alice Paul and all the others were incarcerated it was in Washington. When it was the 75th anniversary of the vote (1995), they had a memorial in Washington, D.C., which I participated in. All the names of the women that were imprisoned were read out loud and I read my grandmother’s name.

When she died, she was only 38. They say she died of an ectopic pregnancy, but it seems my grandfather was pretty abusive. He was married twice, and both of his wives’ death certificates said they died of ectopic pregnancies. That’s just preposterous. What are the odds of two women, both the wives of the same man, dying from an ectopic pregnancy so young?

I’m very excited about this election and I just don’t understand how young women can’t be excited about it. I am working for Hillary. Women don’t know how hard it was to get the vote for everyone. There’s a million Martin Luther King boulevards, but no Alice Paul boulevard. I think that it’s just a forgotten part of history. These young girls today, I could punch a lot of them. You’ll ask these women, “Why would you vote Republican?” They’re so anti-women. Donald Trump is such a misogynist. It’s very hard for me to understand.

Matilda Joslyn Gage

1826–1898

Gage was introduced to suffrage at a National Women’s Rights convention held in Syracuse in 1852. She was a founding member of the National Woman Suffrage Association and published its national newsletter from her living room.

Delphie Broughton, 60, great-great-granddaughter:

Matilda was so radical, so outspoken. She wrote under pseudonyms, under her own name, and of course she published Woman, Church and State. The risk that ultimately led to her kind of being written out of history is that she wanted to include more than just suffrage. She was very much anti-slavery and wrote about that, which was extremely unpopular at the time.

One thing that I think about so much is how incredible the efforts of Matilda and other key suffragists were in light of the times they lived in. Transportation was not easy, and the modern conveniences of electricity, heating systems, refrigeration, indoor plumbing were not available at that time. Life was tough in those days overall. In addition, the child-rearing duties of some of the suffragists — Matilda had four children, two of whom were under the age of 10 when she attended national conventions in Philadelphia in the early 1850s — were formidable. They fought for their beliefs in a time when the country was hostile to them, while managing child-rearing. After Susan B. Anthony got arrested for voting in 1872, Matilda gave 21 speeches in 22 days before the trial began. Wow, she was tenacious and dedicated to her friend and to the cause. They were risking their lives. They absolutely were.

I think Matilda would be appalled at what’s going on. The things that come out of Trump’s mouth are ridiculous on so many levels and are against so many things that she was for. She’d wonder where on earth she was, probably. I’ve thought about how thrilled she’d be that Hillary is running. I think she stands for the same things Matilda stood for. She’s not perfect, but no one is. I’m excited that she’s making history.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

1815–1902

Elizabeth Cady Stanton helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, where attendees constructed the Declaration of Sentiments, which proposed that women be allowed to vote. She was the first president of the Women’s National Suffrage Association and collaborated with Anthony on the first three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage.

Coline Jenkins, 65, great-great-granddaughter:

A lot of the iconic images of her are from when she was older and photography was being developed, but she was only 32 when she wrote the Declaration of Sentiments. She was 32 and had two of her kids at her side, which is a great image for modern women.

These women were the revolution. It was fought without guns but they used every other weapon possible. These women fought for us to be able to vote. And it is not like the American Revolution, which is a seven-, eight-year war. This is so intergenerational. I am unbearably indebted. I stand on the shoulders of all the women and men before me who allowed me to do everything the women in that period couldn’t do.

Nobody sat down and “told” me about Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They were too busy marching in their footsteps and being very powerful women. I just assumed that that was normalcy. At 17 I went up to Seneca Falls and my family took me to the house where Elizabeth Cady Stanton lived at the time. It was a modest house painted sea-foam green. It didn’t really have much of an impact on me. But it takes time. It takes maturity. And I think that as I’m maturing America’s also maturing. That house and the site of the women’s first convention became a national park. And fast-forward and I am invited by Senator Hillary Clinton to testify in front of the Senate subcommittee on Energy and Natural Resources in support of a national women’s suffrage trail.

But this is the really important thing about Elizabeth Cady Stanton: She came from a place of privilege. Her mother was a Livingston and that is a very powerful, prominent family. Her father was a lawyer, a judge who served in the U.S. Congress. Her life wasn’t threatened. She also had a very powerful mind, and logic. She was extremely well read and she grew up in a culture of law. Her father’s courthouse was a couple blocks from their house. She attended the court. They had clerks living with them, visiting. When I asked Dr. Linda Kerber, who was the president of the American Historical Association, “What was Elizabeth’s contribution to America, to democracy, to the nation?” And she said that Elizabeth connected women to law. Elizabeth said, “You need rights.”

Of course I am going to vote for Hillary Clinton, but let it be known that I am a registered Republican and my family helped form the Republican Party. It’s really in women’s best interest to vote. And not just vote but run for office. I have been a legislator for 30 years. When I started, my legislative body was 25 percent women. And I am thinking, Is this representative democracy? Where are the women? I am always asking: Where are the women? I collect photos of the opening of the U.S. Congress and I say, Where are the women? And I look at portraits of the presidents and ask, Where are the women? I look at the statues in Central Park and ask, Where are the women? And there are none — unless you count women from fairy tales.