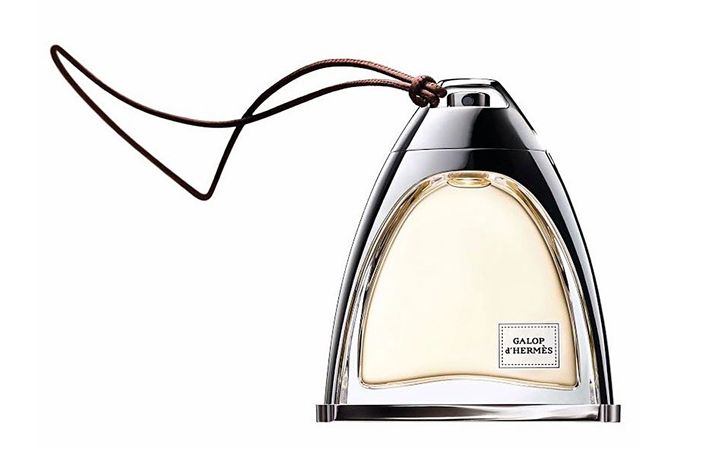

One of the most coveted jobs in the world is to be the in-house perfumer at Hermès. The company discount is a work perk on its down, but the best part of the job is that Hermès perfumers enjoy complete creative freedom — there are no budgets to dictate raw material quality or timelines in which perfumes are required to make their public debuts. After much speculation, the brand announced two years ago that Christine Nagel (creator of Narciso Rodriguez for Her and multiple Jo Malone fragrances) would succeed the much-beloved Jean-Claude Ellena. Nagel debuted her first perfume, Galop, a blend of roses and leather, last month. The Cut caught up with her in Paris to learn more about the one smell she cannot stand, how she broke through the male-dominated perfume world, and what it’s like inside Hermès’s secret leather vault.

You had an unusual start in perfume. Tell us about it.

I started in Switzerland with a background in chemistry. I decided I would like working in a research department at Firmenich. I arrived in the lab and saw through it into another building, where there was a man with white glove putting perfume on women — they all looked so happy.

I said, “What is this job?!” I realized fragrance had a lot of emotion — and that being a perfumer was a job I would like. I asked if I could work in the parfumerie and the response was no. No, because I was a woman, I had children, I did not come from Grasse (I’m Swiss), I was not the daughter of a perfumer, and I studied chemistry. I thought it was really unfair that the door would be closed for me, so I decided, “I’m going to be a perfumer anyway.” The irony is that now, at perfume schools, it’s almost all women.

So what did you do next?

At Firmenich, they told me, “There’s a job, but it’s not creative” — as a chemist. I would smell a perfume and write the formula. At the time, we didn’t use machines to identify scents — it was all in the nose. You would smell a fresh perfume and pick up orange, bergamot, vanilla, lemon, grapefruit. But it was so specific. We had to know, does the orange come from Israel? Or from California? Or from Italy? It was a complicated job.

All the perfumers are from big schools and I come from a very technical background. But I’m very proud of that because the techniques I studied afford me a lot of liberty.

When you look at a dancer, her movements look easy. But to obtain that kind of grace and elegance requires a lot of work. Being a perfumer is just as demanding: A nose never turns off. Perfumers are always smelling and thinking about scents. At some point, you have to get some distance. Otherwise, you’re sniffing all the time.

How did you go from being a chemist to a French perfumer?

When I started creating perfumes, I went to Italy. Perfumers don’t usually go to Italy — just salesmen. But I went for the perfume opportunities and started working there. I don’t know why or how but in one year, I had won 60 percent of the perfume contracts for the Italian market, from Fendi to Versace. It was incredible.

Then I received a call from the director of Quest International, who created Thierry Mugler’s Angel. We had dinner together in Geneva and at the end of the dinner, the director said, “It’s you.”

I said, “It’s not possible.” A lot of different female perfumers are more famous and have more experience than me. I remember he said, “I didn’t choose you for your past, but for your future.” I signed and went to Paris.

Do you think being a woman affects the way you approach genders in perfume?

For me, it’s not a question of sex but sensibility. It has to do with personality. I like talking and discussing with men and women equally. There are men who have very feminine aspects to them, and the opposite is true. Like Jean-Claude Ellena, I think that perfume has no gender. It doesn’t mean that all perfume is unisex. I know women who wear men’s perfume; they are very sexy and they wear it very well. The same thing with men — some wear roses and it’s perfect for them. So, at the end of the day, it’s genderless.

Most perfumers have their labs in Grasse. But you actually choose not to have your lab there. Why not?

It was very important for me to be in the middle of the leather production labs [near Paris] because they are a quintessential part of the brand. It was here that I discovered the Hermès leather vault — la cave de cuir — it’s a very secret place and I can’t give you the address because it’s too sacred [laughs]. When I saw it, it was just incredible. It had a lot of different leather textures, but also colors like pink, blue, green, and red.

When talking about leather, there are two dimensions, the odor and the touch. I touched a lot of different leathers, exploring what felt right. Some are too incredibly soft: You can trace it with your fingernail, and the trail vanishes. Some are strong, some soft; and the minute I touched this one called doblis, I had goosebumps from its simultaneous strength and softness.

Why did you decide to use leather for a female fragrance? It’s usually more common in men’s fragrances.

At Hermès , we don’t do perfume briefs [a write-up of the perfume vision before it is created], so I have the freedom to do whatever I want. And when I touched the leather, pairings came to my mind. All my life, I had imagined leather as masculine. It’s sometimes used in feminine fragrances, but just a touch. It was important to me to express the femininity of Hermès, and I thought that this particular leather was elegant and soft, like a woman’s skin. I returned to my lab to create an infusion. To do this, perfumers put little pieces into a beaker and after three or four weeks, you filter and filter and you get the odor of leather.

I could have done only that. But it wouldn’t have the tactile nature of the leather. So I thought — rose. Often, if you use rose and leather together, the leather overpowers the rose. Combining the two is a delicate dance. I chose a Turkish rose, which has a stronger scent than other roses. It was thanks to my experience as a chemist that I was able to balance the two notes. When you open the bottle, you don’t know if you smell the rose or leather first. On the skin, it’s the same thing.

Do you feel like it’s an equal balance, like 50 percent leather, 50 percent rose?

No. It’s not a question of percent. Because the leather is more powerful, it’s just a trace and not a big quantity. I added two other ingredients including the saffron, which adds more color and a crunchy aspect to the scent. Back in the day, saffron was what they used to create the color orange. I also added quince — imagine when it is cut, it is textured and juicy, and gives some “skin” to the rose.

You’ve said that you like to create “physical” perfumes. What is the “physical” aspect of Galop?

For me, I see everything in terms of textures and colors so if I am able to evoke that sense of texture and that sense of color, that’s the physicality of the perfume. With Galop, I see fire or some earthy color, like rust.

It’s well-known that there are strange or traditionally unsavory elements in your perfume. Do you classify scents as good or bad?

It’s not good or bad, but interesting. For me, all smells are interesting except one.

Which one?

Throw-up. Vomit. Feces, whatever, doesn’t matter to me, but vomit I just can’t stand.

What about body odor? Some people have admitted to secretly liking that scent.

No. It’s okay. For example, very concentrated cassis might smell like urine. But for us, even when we smell urine, we smell something of cassis. As perfumers, all smells have an interesting aspect.