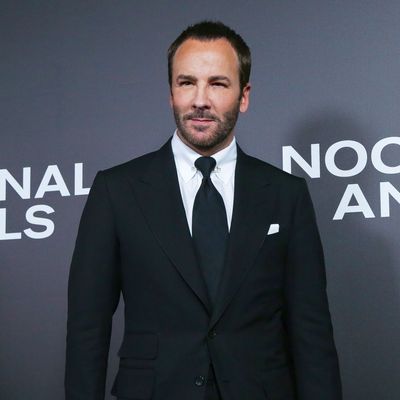

Over the summer, I spoke to Tom Ford for a profile of Amy Adams, who stars in his new film, Nocturnal Animals, which premiered last night at the Paris Theatre. On the phone, Ford, who is from Texas but has the cultured aural affect of 1930s movie aristocrat, sounds like more money and sex than you’ll ever have. (He was calling from his ranch in Santa Fe, which in August he put on the market for $75 million.) Since the film opens tonight, here are some more things he had to say:

The film, which you wrote and directed, is based on Austin Wright’s 1993 novel Tony and Susan, but it’s been significantly changed.

It’s a great book but it was just a jumping-off point to me. The character [Amy Adams] plays doesn’t really exist in the book. I had to make it cinematic. I had to make the story personal. And you always write about yourself.

It’s the story of a suburban housewife who gets an unsettling manuscript in the mail from her ex-husband. How personal could this be?

Amy’s character is basically me. She is a female version of me. Just as Colin [Firth, who starred in Ford’s first feature, A Single Man] was me grafted onto [Christopher] Isherwood [who wrote that novel]: We are all Virgos and constantly obsessed with death.

Why cast Amy Adams as you?

I wanted the character to be sympathetic. She’s inconceivably rich and yet I wanted her to be sympathetic; you can’t be thinking: Why are you moping around? You can’t hate her.

I guess the thing that prompted me to cast Amy was seeing her in Big Eyes. Since she’s mostly reading we have to know what she is thinking and feeling through her face. Her eyes — there’s an instant connection when she looks at you. It’s like you’re looking inside her soul. It’s almost unsettling. And her face: You can believe her as a 24-year-old and the 42-year-old.

Amy was the first and really the only actress who I went to. The same with Jake [Gyllenhaal, her co-star]. I think he said yes in 48 hours.

How is the film about you then?

It’s probably the part of me that you wouldn’t expect. The movie is really about the choices we make in life.

You don’t seem like a man hobbled by regrets. How did you know that Amy knew she was playing a version of you?

She started gesturing a lot with her hands; she said, “I noticed you strike a lot of poses.” But I’ve been striking poses for so long — the gestures she was imitating – that they are natural for me. The way I move and gesture, it’s become me.

You could have cast a more fashion-oriented star. Unlike a lot of actresses, Amy’s not a front-row fixture.

Not so much. She’s not not a fashion person; she’s a serious actress, not that you can’t be a fashion person and be serious. But her work and her family are key to her.

What did you learn from editing the film?

You get to know actors incredibly well when you edit them. You spend seven months in a room with them. You learn every one of their mannerisms. You become so intimate with literally every move and every hair on their neck. You really do feel like you’ve had a relationship with the actors. And they don’t feel that way with you. It’s an incredible, intimate thing, even more than the filming: You are a voyeur.

I know every inch of Amy’s body and every shape of every tooth; it’s like we’ve been sleeping next to each other, it’s like we’ve been kissing for seven months. I know the pattern of her breathing.

Wow. What was it like on set then?

Oh my god, I appreciated Amy as an actress before I started working with her. But I was seriously not prepared for how incredible she is. We’d start filming and you’d think: It’s so real. Is she acting? She’s such a complete pro. Not everyone is. And her face! Oh, her face. You’ll know exactly what she is thinking and feeling.

She’s apparently known for her preparation, building out the characters in her head.

All good actors do that: Laura Linney, who plays her mother in the film, studied tapes of Lady Bird Johnson. She sent me pictures of houses, asking me to choose which one she would live in.

What took so long to make the film?

A friend of mine, Tim Blanks, who is a journalist in London, told me to read the book. But the estate wouldn’t sell the rights till it was re-released in the United States. Then I had a child almost four years ago. I’d said I wouldn’t write another screenplay till he was 3, but the option was running out. I wrote the screenplay two summers ago in Santa Fe.

What else has changed from the book?

I did change the setting, because the plot wouldn’t work in the age of cell phones; I had to find a place where there would not be cell-phone service. And so I moved it to west Texas, which is a world I do know.

You’re a successful fashion designer. Why bother making films?

I am a commercial fashion designer. It is an artistic endeavor, but it is commercial. It has to sell. It’s not that filmmaking isn’t commercial. I hope that this does make money. But it’s not my primary reason for making films.

What is?

It is a personal expression, and it lives forever. There is something very frustrating about fashion: that moment, when something is new, it doesn’t last. A film is forever, forever, forever. You can turn on any old movie and you are with those people even though they’re all dead. It is forever sealed inside this bubble.

Also, fashion only speaks to some people, not everyone. Especially in a country where the people have stopped wearing clothes like this one. We’ve become a country of giant infants wearing pull-on pants and soft shoes and sucking on Big Gulps.