Are you having trouble mourning George Michael because you think he was tacky? It’s true that in the beginning he was tacky, back when it wasn’t cool to be tacky — when we were sick of Reagan and yuppies and all that they had wrought. The floofy, highlighted hair, the dangly cross earring, the precisely groomed Miami Vice stubble topped off by his you’ve-got-to-be-kidding-me assertion of heterosexuality: tacky. Artifice dictated by commercial motives: tacky.

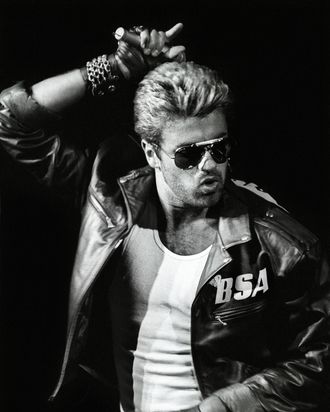

But as he matured, progressing from pretty little girl (Wham!) to twink (Faith), he embarked on a gender-bending project unprecedented in the pop landscape. Here, you had this bearded man vehemently asserting his attraction to women while wearing a weird ’70s gay clone/’80s rocker costume of aviator shades, tight jeans, one glove, dandified cowboy boots, and a motorcycle jacket dangling a string of … pearls? A whole lot of emotive vulnerability wrapped in a hypermanly shell? We gay men and lesbians knew a butch queen when we saw one.

Michael’s lightly coded messages resonated with many young proto-queers, and especially so with young butches, including my friend Sam Greenleaf Miller, who was, as she puts it, “a little guy” of ten when Faith came out in 1987. “I didn’t necessarily know he was gay, but I knew he was really into women in this hot butch way that felt very different from other straight male pop stars. It felt more kinky. Prince was kinky, but he was kind of femme and George Michael was butch. The five o’clock shadow, the leather jacket, the jeans, the whole Harley-Davidson look but explicitly sexual — I had never seen that all wrapped in one human.”

Bearing that in mind, can we be a little more generous toward the young Michael, put aside some of the disdain we might have felt for Wham!? Calling Wham! silly is like calling jellybeans silly. Of course Wham! was silly. It was teenybopper music — catchy, naturally upbeat, crafted for young girls, and sung by pretty, hairless boys with long eyelashes wearing short-shorts and crop tops. Also, Michael and Ridgeley were 18 when they formed Wham! in 1981. I think very few of us look back with pride at our oeuvre circa age 18.

Faith was released when Michael was 25 and the rest of us were just starting to queer-theorize, so we were thrilled to have something so embarrassing, hilarious, and fascinating to pounce on. Greenleaf Miller says she was transfixed by the way Michael’s swagger was balanced by heartfelt ballads. “There was some quality in the way that he was emotional that I connected to. It had to do with being a sexy butch guy who was also able to have feelings. There was something about a man having feelings, so much sadness and loss and grief — it felt really profound.”

1990 brought the big one, the one I consider his best: Listen Without Prejudice, Vol. 1. Its suite of mournful, elegaic songs about longing, loss, and the inevitability of that combination, alongside the exultant explosion of “Freedom! ’90” seemed to my twentysomething self a perfect encapsulation of the time: the sorrows and horrors of AIDS and the love, hope, and desire that persisted among the living and filled our memories of the dead.

The album’s blend of sexy, heartbroken sorrow and hopefulness moved me more and stayed with me much longer than I admitted at the time. (Long after Wham!, he still wasn’t cool in my white alterna world where pop ranked behind rock, punk, and hip-hop). I danced to “Freedom! ’90” in public, but it was the ballads I belted out in private over and over again. “It’s the ones who persist for the sake of a kiss who will pay / Cowboys and angels / They all take a shine to you / Why should I imagine that I was designed for you / Why should I believe that you would stay.”

In 1990, Michael still wasn’t out, which by then we all thought was absurd, but also incidental — Elton John had just come out two years prior and Liberace never did. The big reveal felt, at least in my circle, completely beside the point. It’s not as if Michael was allocating AIDS funding, and to anyone who was paying attention, it was clear that Listen Without Prejudice was his coming-out record.

The fact that the video for “Freedom! ’90” featured all of the top supermodels of the era — Linda, Naomi, Christy, Cindy, Tatjana — was in itself “super-gay,” as my friend Mike Iveson Jr. puts it, and not just because for decades gay men have used glamorous, beautiful straight women as their stand-ins. “The supermodel thing was a super-gay obsession at the time. It starts with Paris Is Burning, which came out the same year, and then everyone was like ‘Oh right, we’re obsessed with supermodels,’ but it wasn’t mainstream to be obsessed with supermodels — it was a thing you discussed with faggots.”

But the closet was still real enough that in 1993, Michael’s HIV-positive boyfriend Anselmo Feleppa, fearful of the light Michael’s fame would shine on him and his family, opted out of treatment in London and instead went to his native Brazil, where he died of a brain hemorrhage. “I’m still convinced that had he been in the USA or London, he would have survived, because just six months later everyone was on combination therapy,” Michael told GQ in 2004.

In 1996, after a long battle with his record label, Michael released Older, dedicated to Antônio Carlos Jobim and Feleppa. The sound was richer, jazzier, more knowing — older. He’d also ditched his luxurious mane, shaving it down to a very gay fuzz, and had gotten a goatee to match. All the signifiers were there, including “Spinning the Wheel,” a song narrated by someone worrying his lover is out having unsafe sex.

And then — praise be — Michael was forced out, caught cruising in the men’s room at a park in Beverly Hills in 1998. His response was so refreshing: a shrug and a laugh; the production of a kitschy single and video, “Outside,” punctuated by the wah-wah guitars of ’70s blaxploitation flicks, that poked fun at himself, at the cops, at the whole escapade.

While norm-y gays were starting to push for marriage and inclusion in the military, Michael came out as a different sort of role model, as a randy faggot, a libertine. He began to speak openly — about his loves and losses, drug use, depression, his commitment to his boyfriend, and strangers met at urinals — putting a very refreshing spin on the conventional narrative where one comes out and then makes up for the disruption by politely subsiding into convention: marriage, monogamy, kids. No thanks, he said. I think I’ll have another joint and a bit more cock. And me and my friends thought: Good for you, George. Live your creation. Sex is natural / sex is good / not everybody does it / but everybody should.

Like the best friends and lovers, he was messy, he was brave, he cried with us and urged us to have faith. “And it’s hard to love, there’s so much to hate / Hanging on to hope / When there is no hope to speak of.” Thank you, George Michael, butch queen of our dreams.