The Science of Us team gets so many science books sent to our desks that we could construct a decent-sized fort out of them. Perhaps one day we will. For now, however, we have sorted through the piles and emerged with our very favorites, all published this year, and presented here in no particular order.

The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds by Michael Lewis

“If you have any interest in the science of human judgement, decision-making, bias, and irrationality, you need to read Lewis’s latest. In it, he traces the story of the profoundly important friendship and collaboration between Israeli psychologists Danny Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who rewrote the ‘rules’ of human nature — that’s the undoing in the title — by asking a bunch of brilliant questions about how people think that no one else had thought to ask. In addition to telling an entertaining, emotionally resonant story of a white-hot intellectual bromance (sorry), The Undoing Project does a nice job explaining why powerful leaders can be so resistant to input from psychologists and other wonks. It’s a point which, uh, might end up mattering a lot in 2017.” —Jesse Singal, writer-at-large

Grunt by Mary Roach

“Roach pulls off something pretty remarkable with this book: making the scientific challenges of warfare seem familiar, even intimate, to those of us whose day-to-day lives have little to no overlap with the military. Each chapter is a reminder that many of the enemies that soldiers face on the battlefield can resemble things that plague the rest of us, too: fatigue, heat, noise pollution. The difference, as Roach illustrates so vividly, is in the stakes: In civilian life, diarrhea can be an embarrassing reason for calling in sick; in war, even today, it can be a killer. And, yes, it can also be funny, which speaks to one of Grunt’s greatest strengths — finding humor and empathy in science that, at first glance, seems deadly serious.” —Cari Romm, associate editor

Cure by Jo Marchant

“I sped through this book like a college kid behind on the week’s reading, as I had an interview scheduled with Marchant and I was woefully behind on prepping for it. The story went up, and I assumed that would be that for me and Cure. Instead, I’ve found myself returning to it often, referencing it when I’ve written about why medication may not always be the best way to treat chronic pain, or about the slipperiness of the term “placebo effect,” or about the surprising efficacy of hypnosis as a treatment for pain, IBS, and other ailments. True, few people at this point would take the full Cartesian view that mind and body are wholly separate from each other; most would concede that something like stress, for instance, takes a physical toll on the body as well as a psychic one. ‘But there’s still the hangover from that sort of way of thinking about the mind and the body as two different things,’ Marchant told me. ‘Of thinking of the mind … [as] being less real, and therefore an unsuitable topic for scientific research.’ Her book will convince you otherwise.” —Melissa Dahl, senior editor

On Trails: An Exploration by Robert Moor

“This book is about so many things: about breaking down the binary between ‘humanity’ and ‘nature,’ ‘civilization’ and ‘the wild.’ It’s an exploration of exploring, a philosophical-psychological-journalistic adventure in the tradition of Michael Pollan and Rebecca Solnit. You will learn about how humans (and other species!) externalize their memories through the paths they make, the tricks of the trade in herding sheep, and the weird, profound, and deeply American history of the Appalachian Trail. Not all who wander are lost, and Moor helps us see what they seek.” —Drake Baer, senior writer

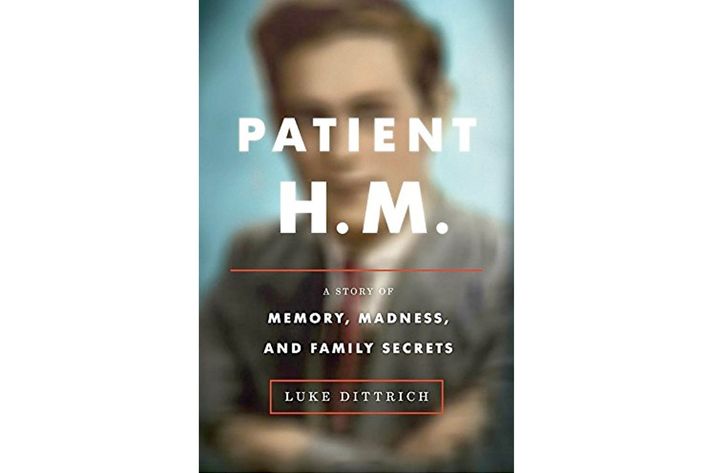

Patient H.M. by Luke Dittrich

“At first, it’s not clear exactly why we need to know more about Patient H.M., the world’s most famous amnesiac and a mainstay in every Psych 101 textbook. H.M., whose full name was Henry Molaison, developed epilepsy after a childhood head injury; by the time he was in his 20s, his seizures were so severe that his doctor suggested a medial temporal lobotomy. And then it becomes clear why this book exists, and why Dittrich was the one to write it: The doctor who performed Molaison’s lobotomy is Dittrich’s grandfather. The book is a fascinating combination of family secrets and history of science; much of it also happens to read like a thriller.” —M.D.