Before strangers would yell at you on Twitter and uncles would scold you on Facebook, socializing on the pre-social-media internet was a land of thoroughly anonymized communities: Usenet message boards around soap operas and ultimate Frisbee, forums for the discussions of computers games and anime, and chat clients for talking shit in-between computer-game matches: StarCraft, CounterStrike, and the like.

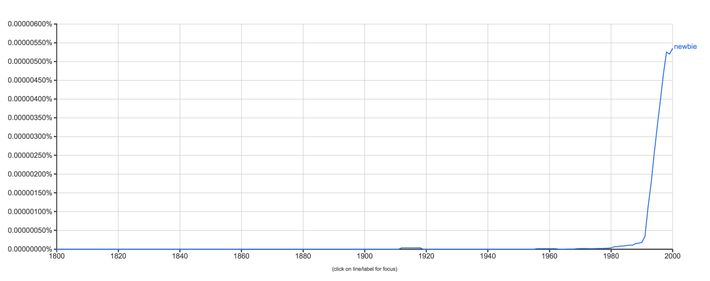

Part of the initiation into any of these nerdy communities was to be, at least at first, a newbie (or noobie, or simply noob). As Dave Shultz details in his sublime “A Cultural History of Noobs” for The Atlantic, newbie goes back at least to a British shortening of “new boy” in public schools (which are actually fancy and old, because England) and military life. As Google’s nGram viewer attests, the word had little published use until the ‘90s and the rise of internet-catalyzed nerdery. Then “newbie” exploded:

To put it somewhat insufferably, to noob is to be liminal, to be on the cusp of in-group and out-group — the long-running form of social sorting that humans are frustratingly, universally prone to. It’s a “tryout phase,” Shultz contends: If a noob learns the customs of a social group, gains fluency in the social signaling, and displays themselves worthy of a community, they may find inclusion, on their way to become leet — old, and later ironic, internet slang for “expert.” It’s right there in the etymology of “learn the ropes”: A novice seaman didn’t know how to tie knots or what rope hauled which sail — so, naturally, they needed a steady hand to teach them the rigging.

Internet researcher Nancy Baym tells Shultz that these experts do nerd-community-specific social maintence, called “noob capture,” to out the noobs in their midst and keep the community cohesive. “It’s a way of preserving the integrity of the practices you’ve developed in a landscape where, on the face of it, your group looks no different that anyone else’s,” says Baym, author of Personal Connections in the Digital Age. “You’re on the same platform, you’ve got the same template a lot of the time. The only thing really differentiating you is the ways that you communicate with one another.”

To be identified as a noob is to then be told to STFU, GTFO, or both. More aggressive casting-out is likely when there’s only limited resources — waves, basketball courts — to go around. Shultz says that as long as noobs are teachable, they’re an asset — after all, they’re how a community grows. A 2007 entry on Urban Dictionary helps refine that further, where the user, one Slyke The Phoxenix, notes that contrary to popular understanding, a noob and a newb are not the same thing. To be a newb is simply to be a beginner, to be a little overconfident, but “willing to learn and fix their errors to move out of that stage.” Noobs are much more problematic: They “know little and have no will to learn any more,” Slyke contends, and their incuriosity is a form of entitlement — expecting others to do their work for them and get praised along the way for it, which is clearly annoying.

As the internet has gotten (marginally) less anonymous, the rancor with which noob gets tossed around has lessened considerably, Australian linguist Michele Zappavigna argues in Discourse of Twitter and Social Media. In the context of forums, noob is a direct insult: “Don’t post pointless replies like this you fucking noob. If your post doesn’t contribute anything, then don’t even bother.” But on Twitter, it’s more likely to be tamed and self-effacing: Does anyone know anything about riding the LIRR?, I’m a noob.

An expert may become a noob again. Gaming scholar Mark Chen documented how that happened in World of Warcraft: when accomplished players wanted to take on the game’s biggest monsters, they’d have to band together in 40-person groups to do “raids” to finish the game’s most challenging quests, which could take up to seven months (!) to complete. These experts would have to take on new roles, learn new forms of communication, and figure out ways to align themselves to goals. “Thus, once-expert players became novices or noobs to relearn expert or leet game play, yet they were not true novices because they had a good understanding of the game system and ways to configure their individual play spaces to be successful players,” he writes. In role-playing games, as in life, if an expert is going to grow, it’s going to require taking on a noob’s mind once again.