“Norma Desmond is one of the great characters ever written for a woman, certainly a woman of a certain age,” says Glenn Close, dressed for comfort in all black as we walk to lunch at Cafe Cluny after dropping off her loyal white Havanese, Pip, at her apartment. Pip was wearing a collar that read BAD TO THE BONE, and he coordinated well with Close’s short, wig-friendly natural coif; they go most places together, it seems. “And now,” Close says, “I’m a woman of a certain certain age.” And she’s back playing Desmond on Broadway.

Close turns 70 in March, which makes her, for the record, 20 years older than Desmond, Sunset Boulevard’s opulently delusional has-been starlet turned murderous cougar. She won a Tony 22 years ago for her first turn as Desmond in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical, when she was only of a certain age.

The new version — as Desmond would insist, it’s a return, not a comeback — is a pared-down one directed by Lonny Price. It lacks the original’s over-the-top production values, in which Close co-starred with one of those elaborate mechanical sets where entire rooms would be lowered from the ceiling. This time around, there’s a 40-piece orchestra in the middle of the stage, which the actors spend a great deal of energy avoiding. “I think I climb up and down more stairs in this one than I did in the original,” she says with mock weariness. “In some ways, I think my costumes were so fabulous because they had to compete with the set. And now it’s obviously much more focused on the characters.”

As it happens, Close kept the lavish outfits, designed by Anthony Powell — a series of Orientalist statement pieces, many in animal prints or featuring tassels or fur poufs — in her personal archive (only taking one dress out, one year, she tells me, for a Christmas party), which came in handy for the 2017 version’s limited-budget production: They’ve just decided to raid her closet and re-use the old ones. “The funny thing is that we had to fit some of them,” she says. “It felt so wrong: It was like I was getting into my grandmother’s clothes.” She even had the monkey mannequin from the original production — Sunset opens with Desmond mourning her deceased simian pal. “He had a nice refurbishment. He has a penis and little balls and nipples. It’s fabulous.”

The musical, based on the 1950 Billy Wilder film, is one of those Hollywood stories that Hollywood likes to tell itself about how corrupt it is to be in Hollywood. In it, Desmond is not only considered a pitiable throwback at 50 — the star Gloria Swanson’s actual age at that time — but was put out to pasture 20 years earlier, at 30. Close didn’t even get her break in film until she was in her mid-30s, in The World According to Garp. But before you think Hollywood’s ageism for women had changed much by the ’80s: In that movie, she was hired to play Robin Williams’s mother, despite being only four years older than he was.

Part of what made Sunset provocative was that Desmond had taken up with a younger man. At least, I say, that doesn’t bother people so much anymore. Close eyes me skeptically. “Don’t you think you have a knee-jerk reaction to that?” she says. “I think it has to do with perception of older women’s bodies: ‘How can someone young and hard be with someone whose skin isn’t hard anymore?’ ”

But none of that is necessarily what interests her most about the musical. “What it says about women is self-evident and almost subliminal,” she explains. “What makes it so relevant is what fame can do to people, the cruelty of it. I think it’s as accurate a picture of Hollywood now as it was in 1950.” She laughs a bit nervously. “I don’t know if you should quote me on that.”

Close keeps her distance from me — literally, because she can’t afford to get even a tiny bit sick if she’s singing every night. She has often played formidable women and has a particular talent for conveying imperiousness as a cover for some other, more desperate and insatiable, need. Part of this is the natural Wasp reserve that goes along with that Pilgrim jawline, those assessing eyes, the fact that her grandparents founded Connecticut’s exclusive Round Hill Country Club. But her history is more complicated than that: When she was young, her physician father enlisted the family in a right-wing movement called Moral Re-Armament, and Close toured the world as part of its musical cavalcade, Up With People. When I interviewed her a few years ago for New York, she told me, “It was a cult, where everyone was told to think alike, and that’s devastating.” After she got out, at age 22, “I decided that I would not trust even my instincts. Because I didn’t know what they were. Everything had been dictated. But it also gives you a huge sense of looking from the outside in, and that has been very good as an actor.”

Back at Cluny, present day, she looks out the window. “You see people in the street and you think, Do you know what you look like? That was my idea for my original Norma: When she looked in the mirror, she wanted to see herself as her youngest and most beautiful self and she was doing whatever she had to do to maintain that illusion. That very, very pale skin and the ’20s heavily kohled eyes. And people looked at her and thought, Oh my God, this kind of gorgon. But she sees something else. But that’s totally different from the Norma I’m doing now.” This time, she plays Desmond as a case study in accelerating delusion, who believes that she is actually turning back into her younger self as her imagined comeback progresses.

Desmond is a camp icon, as is Close: Saturday Night Live’s recent Kellyanne Conway Fatal Attraction skit — a 30-year-old bunny-boiler nobody can forget — shows the pop indelibility of Close’s best work. More recently, people have been obsessed with the steely manipulations of her character on Damages, the lawyer Patty Hewes, whose plot lines often involved what powerful women have to give up to succeed. (Possibly related: Hillary Clinton saw Sunset recently.)

At the performance I saw, two middle-aged gay couples near me, strangers to one another, started talking during intermission: They’d all seen the original production, and while they had their issues with this one’s crowded stage (“It’s like they’re trying to dance in a kitchen,” one said), they loved Close. “She’s been nominated for an Oscar so many times and never won,” said one. “She’s an underdog.” (It’s true: six times passed over.) As the second act gets under way, there is a scene in which Close visits the Paramount lot (67-year-old spoiler alert here), mistakenly thinking her old friend Cecil B. DeMille is interested in her comeback. She is recognized by one of the veteran stagehands, who says, “Let’s get a good look at you,” and puts the spotlight on her. She turns, with regal assurance, into the light, and the man next to me catches his breath and says in awe to himself: “Now, that’s why I came.”

*This article appears in the February 20, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

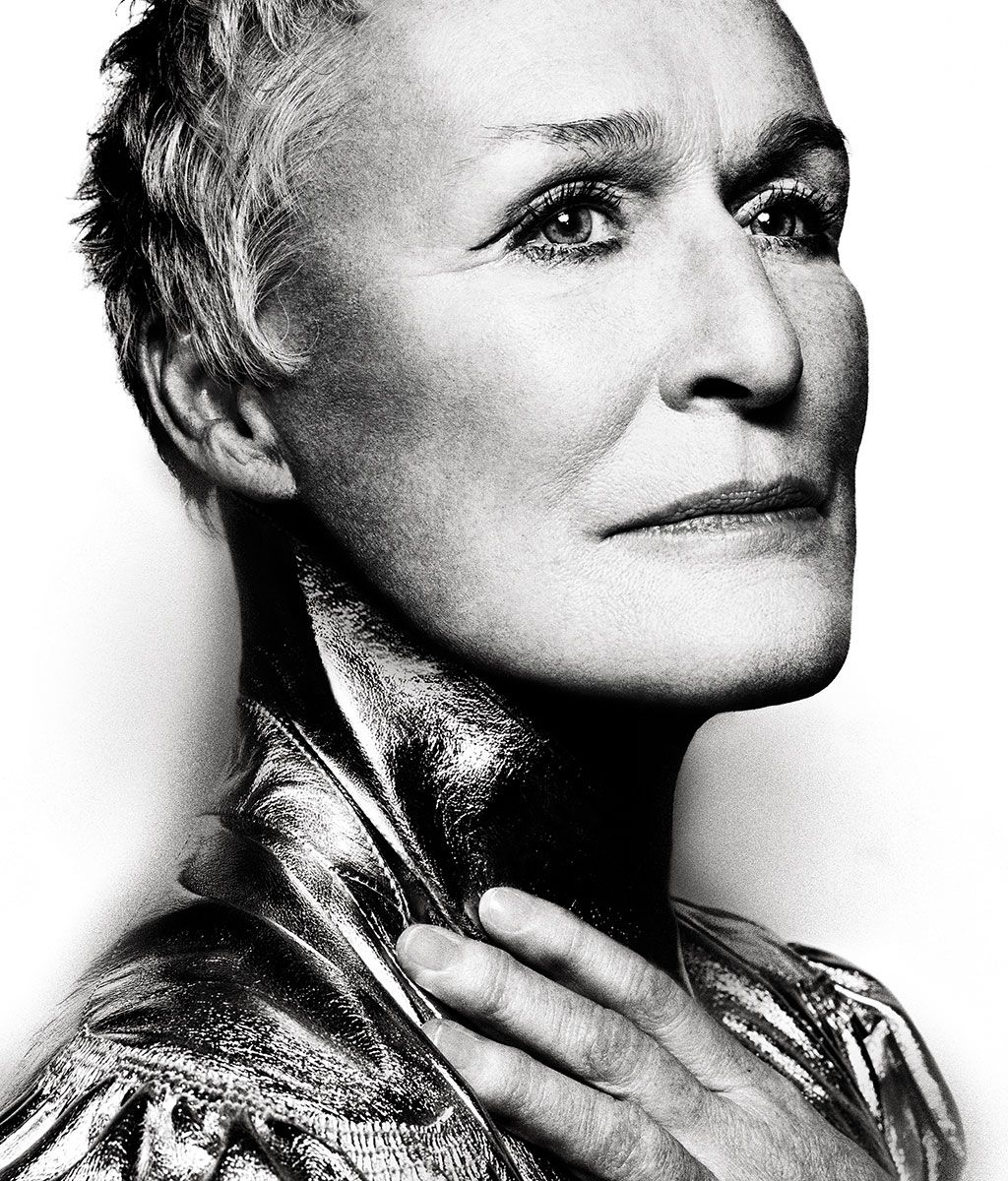

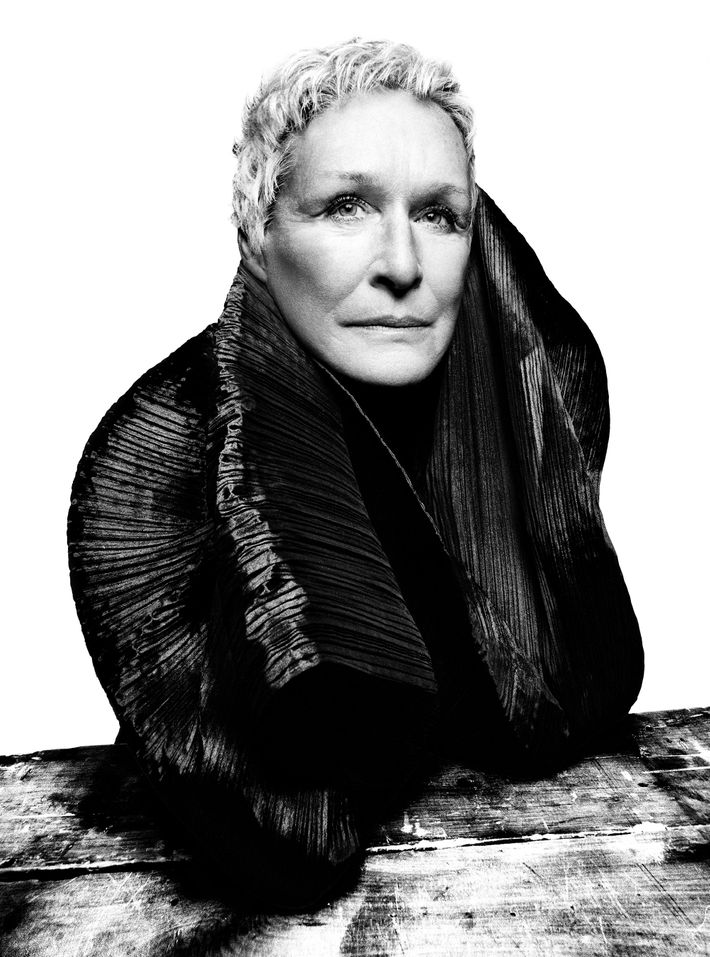

Styling by Michelle Cameron at Streeters; hair by Antionio Diaz using Oribe Hair Care/Bryan Bantry Agency; makeup by Paco Blancas at L’Atelier NYC using Chanel; nails by Isadora using Chanel. Coat by Lanvin (top image). Dress by Issey Miyake (second and third image).