In her new book Dandy Lion (Aperture), curator Shantrelle P. Lewis collects images from around the world celebrating the “well-dressed trickster-rebels” of what she calls a global street-style movement. Dandyism, she writes, is more than dressing up: “A Black dandy is deliberate about letting you know exactly who he is, rather than who you want him to be.”

Photographs from Dandy Lion: The Black Dandy and Street Style, by Shantrelle P. Lewis (Aperture), to be released in June 2017.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.

*This article appears in the March 6, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

Sapeurs de Bacongo | Brazzaville, 2008

La Sape — the Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People — is a Congolese movement dating back to the late-19th century. What began under colonialism has survived as a symbol of resistance, outlasting war and oppression. Sapeurs wear tailored, elegant clothing and compete in fashion battles, as well as adhere to a gentlemanly code of conduct. “White people invented the clothes, but we make an art of it,” said the legendary Congolese musician Papa Wemba, known as le pape de la Sape (the Pope of the Sape). This photo shows Sapeurs gathering to honor the memory of a late friend.

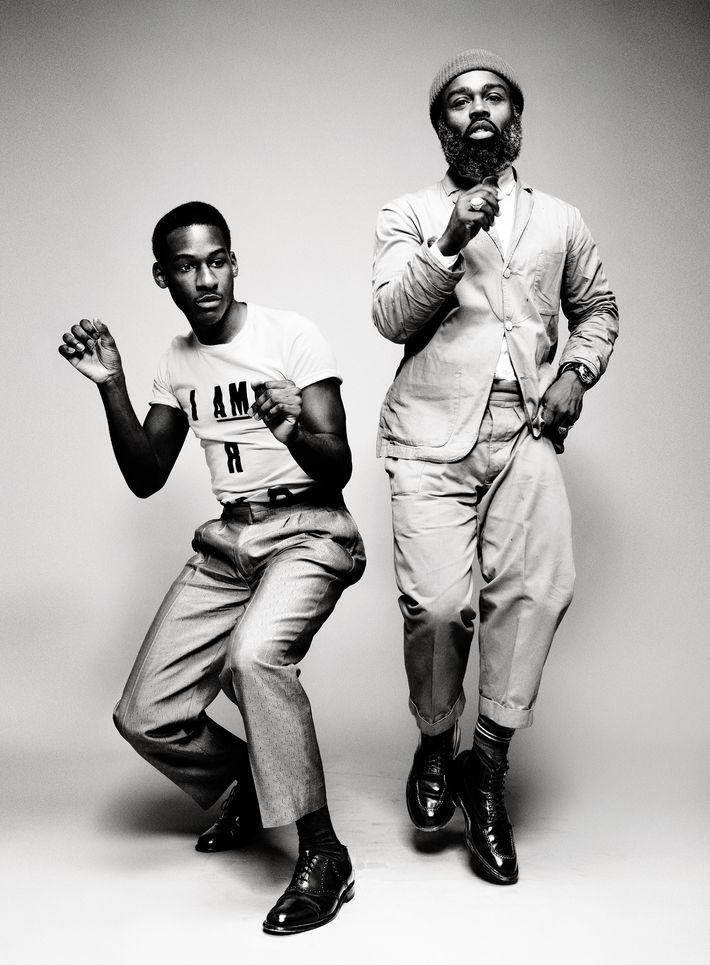

Leon Bridges and Brooklyn Circus | New York, 2015

Leon Bridges is an R&B musician; Ouigi Theodore (right) owns the clothing store the Brooklyn Circus. They’re both leaders in the black-dandy movement and met each other through the style circuit. Bridges’s shirt — which reads I AM R AND B, a tribute to civil-rights-era I AM A MAN signs — was a collaboration between the two men.

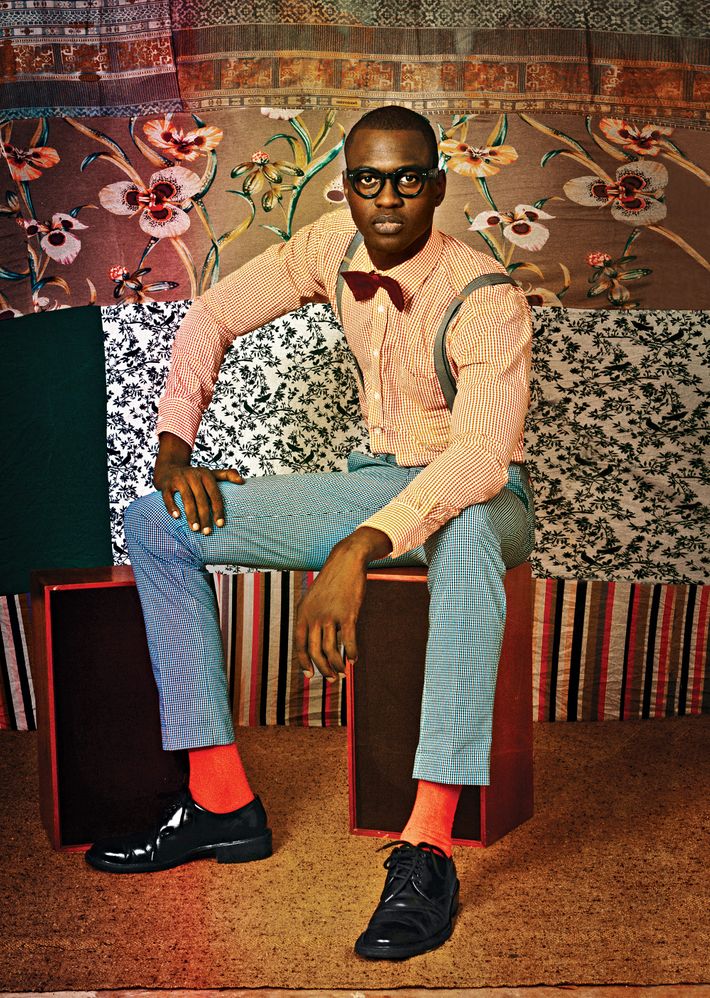

Thierno | Dakar, 2012

Omar Victor Diop is a Senegalese artist based in Dakar — his brightly colored studio portraits refer to the work of West African predecessors like Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta. “Le Studio des Vanités” is a portrait series depicting the world of Africa’s creative urbanites. Thierno Ndiaye, pictured here, is a model, fashion designer, and actor.

Slumflower for Street Etiquette | New York, 2013

Joshua Kissi and Travis Gumbs, former high-school friends from the Bronx, founded the style blog Street Etiquette in 2008; the editorial shoot “Slumflower” took place at a Chelsea housing project and starred their friends. It was conceived with a few simple questions in mind: “What if all the men here were wearing suits? Would people be less afraid of the projects? Would they care more?”

V for Victory | Johannesburg, 2014

The South African collective Khumbula took its name from the Nguni word meaning “to remember.” The group draws inspiration from anti-apartheid freedom fighters. From top, the members pictured are Bafana Mthembu, David Maledimo, and Andile Biyana.

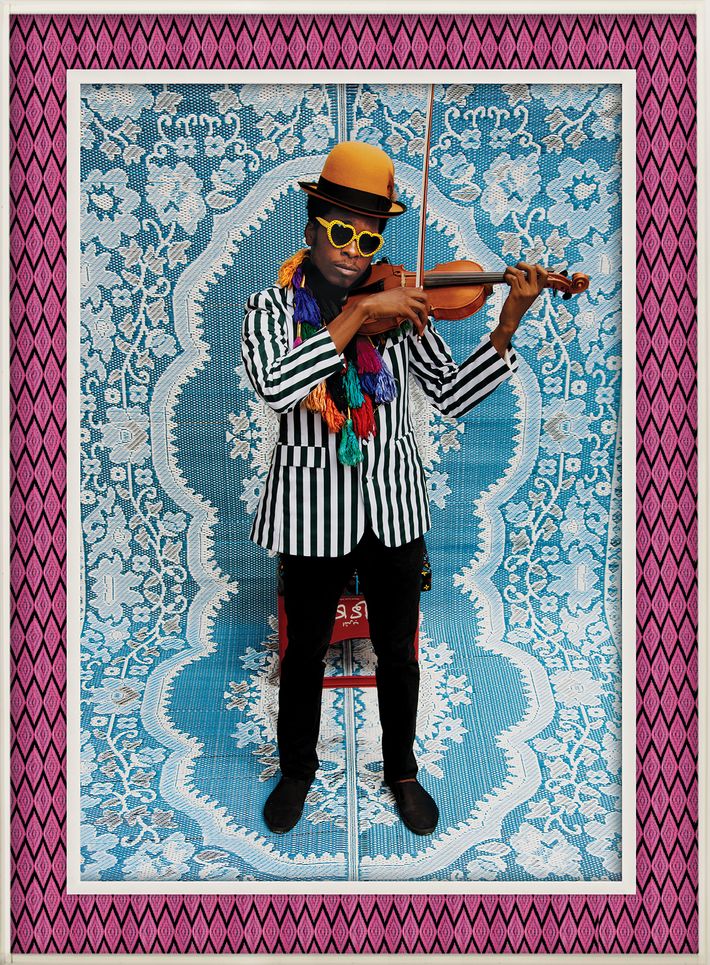

Mr. Toliver | London, 2010

Hassan Hajjaj lives and works in London and Marrakech, where he makes vibrant, stylish portraits in collaboration with both his subjects and a tailor. This photo is from a series called “My Rock Stars,” which features international musicians and performers — like Marques Toliver, an R&B singer and classically trained violinist.