Continuing the Cut’s series celebrating women in the arts, and expanding on the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ social-media campaign to get their followers to name #5WomenArtists, we asked female art professors and teachers to tell us about the female artist they admire the most. For more, see the first entry in the series — female curators and gallerists — here.

Niki de Saint Phalle

“I love the work of Niki de Saint Phalle because she’s fearless. And her work on the Tarot Garden Park in Tuscany is my favorite piece of hers because it is relentless.”

–Angela Dufresne, assistant professor of painting, Rhode Island School of Design

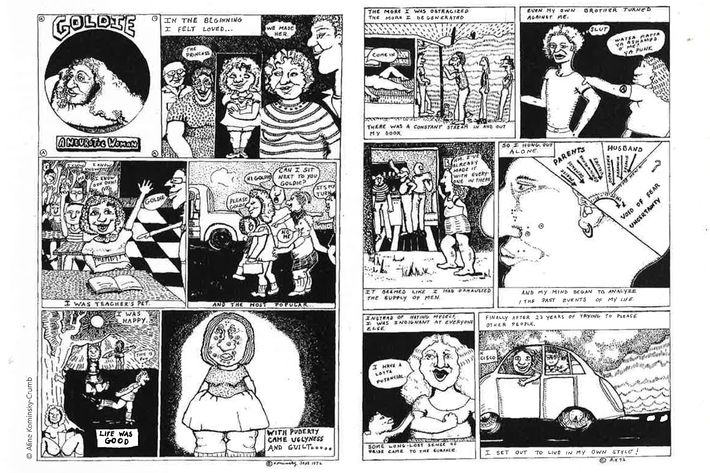

Aline Kominsky-Crumb

“I didn’t truly understand the implications of identifying as a feminist, and perhaps more significantly, the complexities there within, until I came across Aline Kominsky-Crumb’s comics. A professor gifted me a book of underground comics-artist interviews my junior year of college and Aline’s work was in it. [Her work] was a respite from the world I was slowly becoming at odds with at my liberal-arts college. Coming upon her comics, I realized how exhausted I was trying to convince myself that I was some kind of delicate upstate New York sylph in a sundress, smiling beatifically through another acoustic-guitar jam at yet another potluck. I was actually a thick-thighed frizzy-haired opinionated Jewish girl from suburban Connecticut who liked boys and hated being told what to do. Perhaps on a good day I could be some of both, but that I could identify as more than one thing at any given time blew my mind, so Aline’s voice was a real godsend to me. My work never grew to resemble hers in any way, but the backbone of my interest in confessional work stems directly from hers.”

–Alex Citrin, illustrator and professor, Pratt Institute

Rebecca Horn

“I have a lot of favorite artists and many of them are women. I love them for so many reasons; for things they’ve said, a work they’ve made, or an image that I hold onto and refer back to from time to time. I love Rebecca Horn for her magical, powerful observations of the invisible forces of nature that flow between animal, insect, and human. Her works are infinitely fascinating to me. She not only makes the invisible, visible; but she also understands how to create a charged exchange between viewer and viewed. One of my favorite works by Horn is Mechanical Peacock Fan, in which she isolates and mechanizes the display of a male-peacock tail. The mechanized tail fans open and then close over and over and ever so slowly. It’s a deceptively simple gesture; one in which a sense of desire and yearning becomes palpable.”

–Rachel Berwick, professor and department head, RISD Glass

Corita Kent

“Designer, printmaker, artist, and educator Corita Kent has been a longtime inspiration and guide. Every time I drive by that natural gas tank just outside of the city of Boston, I feel a kinship and comfort in her exuberant stripes and colors. I have long enjoyed all the urban myths regarding various images that can be extracted from the paint strokes. I imagine Kent would have liked that, people looking deeply and intuiting messages beyond the surface. Her rules for students and educators are lighthearted but exactly on point and they serve as a foundation for my own teaching practices. Her work is bright, daring, and subversive.”

–Nikki Juen, instructor and lecturer of experimental and foundation studies, RISD

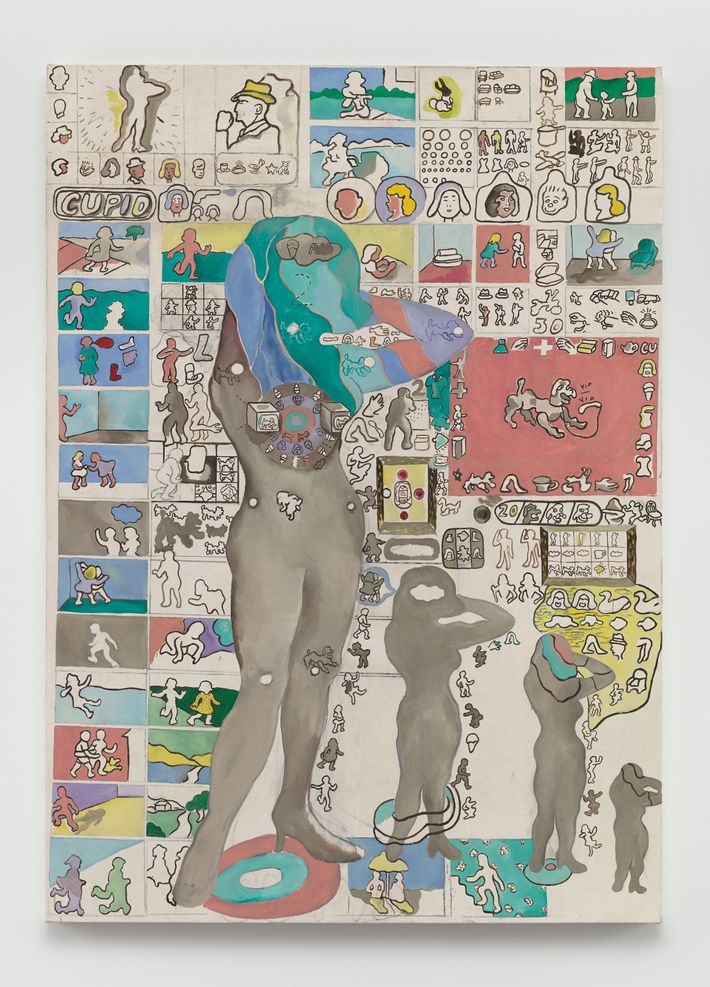

Suellen Rocca (and others!)

“It’s always challenging to choose favorites but I’ve been compelled recently by the work of a variety of female artists including and of course not limited to Genesis Onasis, Suellen Rocca, Sally Saul, Brie Ruais, and Louise Bourgeois. What these artists have most in common is their distinct and tactile response to the body as well as the degree of humor and the disturbed embedded in their work. I’m taken by the way that each of these women use the scale and medium of their work to elicit a visceral and familiar experience in the viewer. Their works deliver moments both haunting and absurd, filled simultaneously with comfort and disquiet.”

–Jaqueline Cedar, artist and educator

Agnès Varda

“Agnès Varda, the French New Wave filmmaker, invented her own feminist language of film, both personal and political. My favorite work of hers is Vagabond (1985). An independent young woman takes off on a road trip walking, hitchhiking, meeting people, negotiating her needs. The structure of the film is inventive, unfolding in short episodes that shift from her perspective to the perspectives of people she encounters. Vagabond begins with the end. Clearly Varda was looking to challenge the form of storytelling through narrative structure and subject matter while making a case for the independent woman. Her agenda is ever more relevant today.”

–Perry Bard, professor, School of Visual Arts

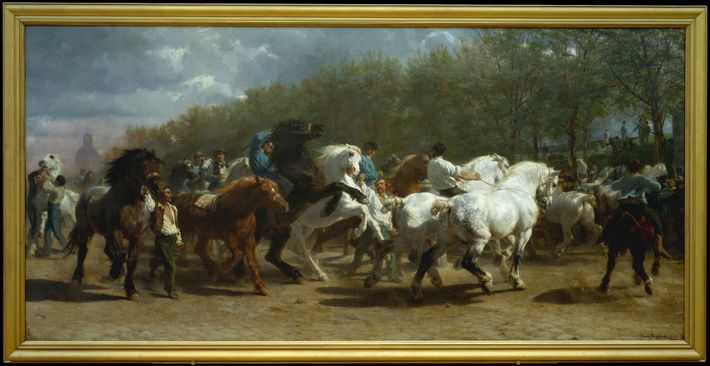

Rosa Bonheur

“When I was about 7 years old, my father took the family to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He pointed out Rembrandt and other great masters, all men, to the family. Then we came upon Rosa Bonheur’s painting, The Horse Fair. I froze in front of this huge study of horses painted by a woman. Bonheur’s emphases on motion and anatomy fascinated me as a child, and have continued to be important elements of my own art.

But it was not only Bonheur, there were many women artists since those tender years who have been influential to my work: Mary Cassatt’s focus on mother and child tells the importance of personal experience, Georgia O’Keeffe’s strength to hold on to her personal vision of life by magnifying details that are normally overlooked, Frida Kahlo’s ability to use her own physical pain to produce her powerful art, and Alice Neel’s capture of the inner human spirit through her portraits. All of these women and others have been significant in my work, but Rosa Bonheur was first to give me courage to believe women have something important, something special to share with the world. This is the most important influence of all.”

–Margo Mead, artist and art educator at an all-girls school in NYC

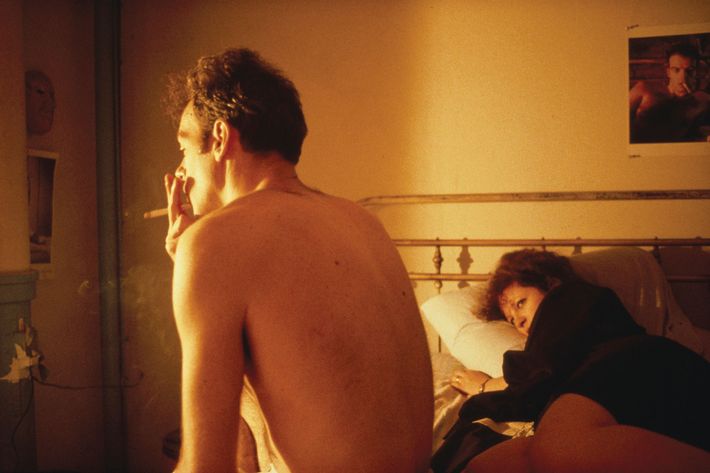

Nan Goldin

“I love Nan Goldin because her work is always honest, direct, emotional, human, unapologetic, real, deep, complex, and never pretentious. Nan One Month After Being Battered is my favorite image of hers because I love the conflicting elements that are so much what life is about in such a universal way … the weakness and the strength, the beauty and the flaws, how direct yet mysterious life is. I love the colors, the flash light. With the title, we are given only some information, but its meaning grows and grows in my mind and imagination.”

–Elinor Carucci, faculty, MFA Photography, School of Visual Arts

Adrian Piper

“I find Adrian Piper’s work intellectually evocative, socially provocative, viscerally haunting, and fearless. My favorite work of hers was a video installation entitled Out of the Corner that she showed in the Whitney Museum of American Art in fall 1990. Triangulating a corner of the Whitney gallery, 17 monitors were defiantly perched on pedestals. The first monitor, positioned in the corner itself (with an overturned table blockading the pedestal’s base), displayed a 17-minute video of Piper herself speaking about interracial lineage or miscegenation, citing that many of the “white” members of the audience might be, according to such laws or conventions, classified as black. Along the two adjacent walls on either side of the corner display 64 black-and-white portraits of black women who Piper has rephotographed from Ebony magazine. Piper extends the barricade out into the gallery space with 16 additional monitors on pedestals, each of which is further blockaded by an upended chair with its legs disconcertingly pointing towards the audience. Midway through Piper’s monologue, the other monitors are triggered in succession displaying 16 apparently white faces whose speech, and sometimes textual assertions, belie the racism implicit in the assumption.

As the monologues end, Piper asserts the playing of Sister Sledge’s song ‘We Are All Family,’ thus, concluding one playing of the installation, which then loops repeatedly. In Out of the Corner, Piper fearlessly interrogates the notion of racial classification and stratification as well as implicating the audience in their possible complicity. The radical inquiry of this artwork has influenced my life, my art, and my worldview, and continues to haunt my own notions of a radical art praxis.”

–Maureen Nappi, artist and professor of media theory + CGI, Long Island University

Clarina Bezzola

“I love this work of Clarina Bezzola’s because it literally screams the pain and sorrow of not only death, but life as a woman. Seeing this work of hers in person really had an impact on me as a young artist who performs and makes imagery about the female body. Here she is carrying burdens and labor in all its manifestations.”

–Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow, faculty, School of Visual Arts

Lizzie Borden

“I’ve been thinking a lot about Lizzie Borden, and more precisely, her 1984 film Born in Flames. Raw, loving, subversive, and warmly human, it is a bomb thrown into the history of cinema and life, a bomb that couldn’t be more relevant today.

The film is set in New York City ten years after a peaceful socialist revolution, where not surprisingly, men are still in control. Sexism, racism, and classism thrive, and the film documents the struggles of various women’s groups as they discuss differences of ideology and position, weighing nonviolent versus violent tactics. This is a film about conflict, resistance, support, and finally action, as these disparate women join together to take control over the airwaves.

Borden shot Born in Flames without a script and with a micro budget of $40,000 over the course of four years, and it has that destabilizing, not-knowing-what-will-come-next feel as we follow Borden’s process of exploration, questioning, and radicalization. It’s a film about engagement and pleasure, that gloriously leaves its seams exposed. Borden is wildly successful in capturing the raw vibrant energy of the taken-apart NYC of the early ‘80s before the rich laid claim to it — where every store, doors open, every boom box on every corner, gave the city its beat. And the cast of (mostly queer) women take hold of this power. The film is threaded with the voices of two compelling performers, whose characters both work for pirate radio stations. There’s Isabel, the angular lesbian punk anarchist of Radio Ragazza, who raps: ‘How does one illuminate a dark and lonely sky? There’s only one thing left to do, you gotta ram in the darkness with your rhyme.’ And then there’s Honey of Phoenix Radio. Looking directly into the camera, her riveting face covering most of the frame, she appears to be speaking personally to each one of us as she says: ‘Freedom, it’s yours, it’s right here and it’s your right. They may label you, try to classify and even call you a crazy bitch, but don’t flinch, just let them … Exercise your rights and your freedom is yours. Black women, be ready. White women, get ready. Red women, stay ready, for this is our time and all must realize it.’ We are born in flames.”

–Shelly Silver, associate professor and director of moving image, Columbia University