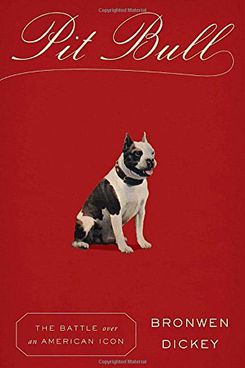

The award-winning journalist and Oxford American editor Bronwen Dickey spent seven years researching and writing Pit Bull: The Battle Over an American Icon (out in paperback April 4), the most authoritative tome on one of our country’s most polarizing breeds. Though the impetus for the book was Dickey’s own stereotype-defying pit mix Nola, the author never fawns over the animals. Instead she takes a long, sober look at their history and warns against both deification and demonization. “You say the words ‘pit bull,’” she says, “and people lose their minds scrambling to one side or the other.”

Pit Bull dispels myths perpetuated by both sides. No, their jaws don’t lock — but they were never “nanny dogs,” and you should never leave one alone with a child, because you should never leave any breed of dog alone with a child. Cropped ears don’t mean a pittie’s a fighter (the opposite, in fact), and scars don’t out it as a “bait dog” — a helpless, chained dog purportedly used to test or rile up a fighter. “There’s no mention of bait dogs in the entire history of fighting literature,” Dickey says. “It wouldn’t serve any purpose.”

If a “pit bull” shows up at a shelter with scars or broken bones, people often assume it was a fighting or bait dog. But it’s far more likely the dog was hit by a car, harmed in an accident, or otherwise abused by its owners. These myths — some of which mean to elicit sympathy for pits — only serve to further link the dogs to combat, which is misleading and counterproductive.

Dickey consulted dozens of animal experts and pored over mountains of data before emerging with a conclusion as mundane as it is profound: Pit bulls are just dogs. All too often, they serve as a proxy for our own prejudices.

One of the experts in the book says that the best thing that could happen to pit bulls would be if everyone stopped talking about them. Do you agree?

I one-hundred-percent agree, which is why the book-publicity cycle has been odd. Now I find myself needing to spread the word about the book —when the message of the book is that the best thing we could possibly do for these dogs, or any dogs, is to sideline the breed obsession and focus on what unites all people and all dogs, and what humans and dogs have been sharing for many thousands of years.

Our breed fixation is so historically recent. We’ve lived with dogs for 35,000 years at least, and this breed fixation only started in the mid-19th century. So we’re looking at this tiny drop of history, and the way our culture is now — with marketing and branding and sorting ourselves into tribes — the breed thing has become all-consuming.

“Pit bull” is such a huge category with so many millions of dogs. There are at least four pedigreed breeds, and then you have people lumping in the mixed breeds and the dogs that are just kind of stocky or whatever. Once the pool gets that big, you can’t generalize anymore. At this point, “pit bulls” are as diverse as Americans.

Which breeds comprise the “pit bull” label?

It’s so incredibly subjective, and that’s one giveaway that the scary statistics that you might come across are garbage — because no one can even define “pit bull” or agree on what it means. Everyone agrees that the pedigreed American pit bull terrier would be included in it, but for some people that would be the only dog that qualifies as a pit bull. Then there are all these offshoot breeds, or dogs that look very similar. In the book I define it as the American pit bull terrier, the American Staffordshire terrier, the American bully, and the Staffordshire bull terrier, which is the little pint-sized English version.

A lot of times when you see the “pit bull” headline, the dogs that are referred to as pit bulls are just mixed-breed dogs. It’s like we’ve come to use the term “pit bull” to mean “dog not otherwise specified.” So if it has a short coat and they don’t know what it is, there are many people who will just call it a pit bull. Or if it has a brindle coat, then that’s a “pit bull.”

How successful are people at identifying dog breeds — including “pit bulls” — on sight alone?

Not very. Scientists have done studies where they take animal professionals— shelter workers, veterinarians, animal control officers, etc. — and show them photo arrays and video clips of dogs, and ask them to give their opinions as to which breeds are in which dogs. More than half the time, not only do the breeds they pick not correspond to what the dogs’ genetic tests say, but very often they can’t even agree with each other. That, for me, is the most damning thing about visual breed identification. Let’s say that genetic breed-ID kits end up being faulty. The fact that so few of these professionals can agree with each other means there is very little inter-observer reliability.

That should really give us all pause. If these animal professionals can’t even agree on a breed, that means these labels that are being put on mixed-breed dogs are arbitrary. A lot of them happen to be overidentified as “pit bulls,” so when you see that in statistics — for example, bite statistics— you can’t trust these numbers because there’s no evidence at all that those dogs are actually members of one of the “pit bull” breeds.

Do pit bull bans and other breed-specific laws work?

No. In eight of the countries that have breed bans, they’ve studied whether or not they actually reduce dog bites and serious bite injuries, and they’ve found that they do not. Leash laws, containment laws, and holding reckless owners responsible are far more effective measures. In Multnomah County, Oregon, they have a Potentially Dangerous Dog program that has been very successful. If a dog becomes a nuisance or menaces people, Animal Control intervenes, checks in with the dog’s owner, and recommends training. They keep in contact with the owner, and that drastically reduces bites because it doesn’t allow things to escalate.

We’ve known for a long time that breed bans don’t work. The laws are way behind the science at this point.

People often say things like, “Pointers point, retrievers retrieve, and pit bulls fight,” implying that violence is in pit-bull-type dogs’ DNA. How does that hold up under scientific scrutiny?

It doesn’t. There are all these layers of nuance and complexity that people aren’t interested in. It’s a lot easier to say, “Pointers point, retrievers retrieve, and fighting dogs fight.” That’s a very soothing and simplistic way of looking at the world, but it’s not really true. Pointers who have been highly selected for pointing will perhaps have a knack for pointing based on the breeder and the processes of selection and the particular line of dog and all these other choices that are being made (how the dogs are handled, how they’re trained, etc). Breeders know how to increase that likelihood, but as one of the trainers I interviewed in the book stressed, “There’s no such thing as a litter of winners.”

That’s true even for behaviors that are relatively simple, like pointing and retrieving, which are also highly advantageous to the dog. They help it secure food. But breeders who are trying to breed for fighting — which are extremely rare these days, with awareness so high thanks to Michael Vick —have a much harder uphill battle, because (a) fighting is incredibly complicated; and (b) it puts a dog at a disadvantage evolutionarily. Dogs are very social creatures; they live in groups. Fighting other dogs is not conducive to survival. The cruelty-investigators and the experts that I talked to stressed that if a breeder is rigorously selecting for those traits for generations and generations, it still is considered a very high success rate if they get one in the litter who has the fighting makeup.

Dog-fighting historians say that even in the 1920s, only between one and (at the very highest) 10 percent of purpose-bred pit bulls were actually used for fighting. The rest were just general all-purpose dogs. What we know from behavioral genetics is that the behaviors that are not rigorously selected for tend to mellow out over time. So it’s much easier to breed a dog that looks a certain way than it is a dog that acts a certain way.

These dogs have had such an illustrious and complicated history in America, and yet fighting is the first or only thing people associate them with. It’s really sad.

Can Patrick Stewart single-handedly repair the pit bull’s image?

[Laughs.] Well, I don’t think anything can do it single-handedly at this point, but I love those posts and the fact that all the wonderful things he’s doing with Ginger are the wonderful things that anyone would do with any dog. The more people who see that normal, everyday human-dog friendship, the more we’ll all collectively get over our breed fixation and move on.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.