You get the idea, meeting him as I did on a recent afternoon at the Sperone Westwater gallery on Bowery amid his peculiarly assertive, fossil-like memory-foam sculptures, shellacked wall objects (some of which look almost edible, but of course are not), and husk-like pieces dangling on meat hooks from the ceiling, that Helmut Lang doesn’t forget much. That he’s always working through his past, rummaging around in the idea of it, transforming it, and also hoping, perhaps, in that way, to leave it behind. And he’s left a lot behind — insofar as that’s possible, as there aren’t many artists who share their name with an iconic fashion brand (with a shop in the Meatpacking District) they haven’t owned, or been involved with, in over a decade. That brand continues on without him — even as artist Lang was preparing the show in mid-March, it was announced that HBA’s Shayne Oliver is working with brand Lang now.

In person, Lang, who turned 61 in March, is avuncular but cautious. Even after living for 20 years in New York, he seems to worry that he can’t quite express himself exactly as he wants in English, and, he admits, he would have preferred to do an interview over email. (“I’m very bad at making statements.”) That way he could go over it, rethink what he has to say, make sure it is precisely as he’d like it to be. He is, it seems, an iterative, intuitive, just-so person, a reworker and refiner, which, if you think about the insightful rigor of his clothing, makes sense, but, as he explains it to me, is also how he works as an artist, starting with a material and an idea of what he might do with it, to transform it, or draw out some hidden quality in it, something haunting it. “I am always interested in transforming materials to give them a different meaning or perception,” he says.

As he tells it, Lang, who grew up in Austria the son of a truck driver, never planned to be in fashion. “That turned out to be an accident,” he says (today he is in a sweatshirt with what appears to be a built-in wrist stirrup, jeans, and sneakers). “But a good accident.”

After leaving home at 18 (where his stepmother dressed him in suits that had belonged to her father, which he hated), he found that he had a talent for making his own clothes, and even though he was untrained in fashion started a made-to-measure shop in Vienna. That was in 1977, and by the 1990s he’d become one of fashion’s biggest minimalists. Prada bought 51 percent of his business in 1999. But he never forgot himself in that world, or he tried to keep a kind of distance from it, almost like his success was an art project itself: Once, he scanned a bunch of notes from friends and fashion types he knew, digitally manipulated them, and printed them as an art project in the magazine Purple called “Selective Memory Series.”

He became close friends and art-fashion collaborators with Louise Bourgeois and Jenny Holzer, whose sculptures also showed up in his clothing stores and perfumery (he and Holzer worked together on a piece about, yes, memory — in the form of scent on clothing — at the Florence Biennale in 1996.) One of his ads featured a Robert Mapplethorpe photograph of Bourgeois carrying her latex phallus sculpture under her arm. In 2004, he sold the rest of his fashion company to Prada, and then left in 2005. Since then he’s had shows from Brooklyn to Moscow, as well as Germany, East Hampton and Dallas. His first show at Sperone Westwater was in 2015.

In 2009, he made a sardonic resin piece called Front Row, of five ghostly chairs from a fashion show, which might have seemed like an act of exorcism. And then, in 2010, there was a fire in the Soho space where he kept his archive, and afterward he shredded the 6,000 to 8,000 items of clothing that survived, transforming them into sculptures. And at that point, he was as free of fashion as he was ever going to be, although among the people I saw show up at his opening on March 30 were Grace Coddington and Barneys’ Dennis Freedman.

Mostly he lives in East Hampton now, where his studio is an old barn that was a gift from the heiress and photographer Adelaide de Menil. That’s where he made this work. He doesn’t come into the city much. “I spend more time out there,” he says. “Because the studio is out there. So you work there. So I work basically except now. Of course I have an apartment and everything here but because of the work situation I stay out there.”

Is it easier to make art out of the city?

I think it is less distracting. Working there … you are always removed. In New York there’s always something to do. But I don’t know that I need constant stimulation. That can also be confusing. And you can be noisy or not and nobody will complain. Then in August I don’t work. Basically everybody is out there for one-and-a-half months. Not only from New York but from all over the world. But off-season, sometimes it can feel isolated. The distance matters and doesn’t matter. But then New York is only a two-hour drive away …

Without the summer traffic.

I could have a studio in Brooklyn like everyone else …

Are there still many artists you see out there? It famously used to be, but now I feel like it’s just so full of finance guys when I’m out there it’s hard to remember that legacy.

George Condo is basically around the corner. Nate Lowman is there. Cindy Sherman — there’s at least 100 artists. Not that they’re there all the time.

So let’s walk through the show. This work is all new?

Yes, over the last two years. I like to work in different bodies of work at the same time. You start, you do maybe four or five pieces, and then you stop when you feel that could be a good contribution to that cycle. It’s about taking your time. It just goes until it gets to the point where you decide there’s not much more to say or else you said too much and then you edit it down.

What are they mostly made from?

The basic material is foam. The little ones are silk and shellack. Some are only wax

What unites them? The color?

Their visual chemistry.

These sculptures remind me of animals. Or orc fists. Or dinosaur hip bones with meat on them.

Everyone sees something else in it, which I always think is very rewarding. It’s not one obvious thing … It could also be another body part …

Butts? Are they portraits?

One is a famous butt, one is not famous. That’s a joke.

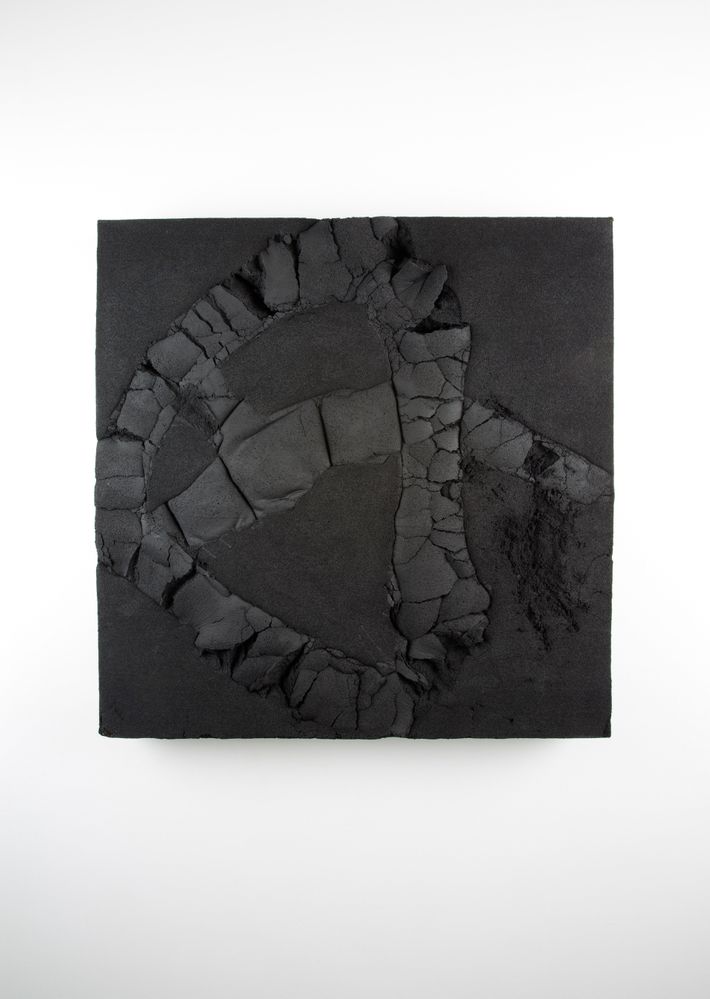

And these wall pieces are also made out of foam?

Yes, I call them reliefs. They aren’t paintings exactly …

Why make it out of shellacked foam?

I work with material which is not typical material you find in the art store. I do either found materials or materials which are natural or industrial and I see where it leads me.

Where’d you come upon this material though?

I got some memory foam like three or four years ago for another artwork I had in mind, which did not work out, and it was just sitting around for a year.

So you didn’t just rip up a mattress.

No, not in that case. It’s foam which has been imprinted by human beings. It’s imprinted over the years by human beings, you can’t see it but you can feel it. The sculptures and the flat work were all imprinted by humans. They had a previous life. But the memory foam upstairs from the previous art work which did not work out, but after a year I found a solution for it …

That’s intriguing. What was the previous life for the foam?

I’d rather not say, because otherwise, it channels your fantasy in one direction …

It’s hard not to when you talk about foam and other people’s bodies.

But it’s already a lot, no? But it’s not coming from what you see. What are you thinking? Let it out!

Well, people having sex …

No. It’s clean. It was covered.

Tell me about these hanging sculptures. They’re made out of resin-coated paper? They look like …

Some people think it has a suggestion of cruelty. [laughs] Skin or husks. Snakeskins if you find that level.

Or an abattoir for aliens. They’re a little creepy.

Not to me. I find them kind of intriguing in a beautiful way.

Looking at it closely, you can see the drip of the resin …

My work, it’s not cleaned up.

And it almost looks like you sewed it …

No. That’s behind me. I might take it up again someday.

Upstairs, there are more memory-foam pieces, with these mysterious circular patterns on them.

They are kind of amputated memories. Frozen.

Did you carve out the foam and stuff this distressed foam back in?

No, but maybe that would have been easier … They have been kind of bondaged. It’s a square piece and they are bondaged together with straps. And the memory foam retains that when you open it up again.

It’s sort of kinky.

If you think about it, yes. But when you’re doing it it’s not. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

That’s one good reason to do your work in the country. Nobody can hear the bondaged foam scream.

It’s pretty quiet actually.

Helmut Lang’s exhibition is on at Sperone Westwater until April 29th. He has upcoming solo shows at Sammlung Friedrichshof (Burgenland, Austria) and Stadtraum (Vienna, Austria) from May 6th through November 19th, 2017.