The signs of the trend came not as a flood last winter, but in dribs and drabs. I’d notice 20-somethings in Patagonia fleece vests thumbing through Lost Downtown at Dashwood; an El Rey waiter ringing up my kale Caesar in a Columbia windbreaker; diners at Win Son in North Face puffers and Acne Adrians; a couple in matching Arc’teryx parkas drinking flat whites at La Colombe. It was amusing, the incongruity of city kids — most of whom would sooner die than drink from a Nalgene — incorporating the hallmarks of camp gear into wardrobes of COS sweatshirts and 3x1 jeans.

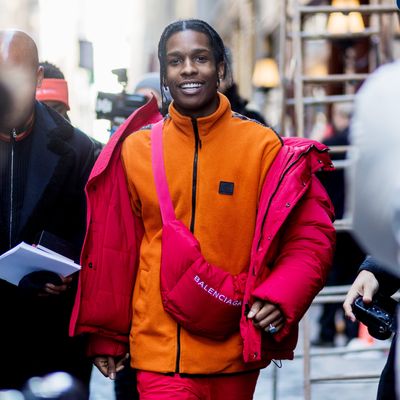

But as winter progressed, it became clear a bigger cultural shift was afoot. There was A$AP Rocky in a full-zip fleece at Fashion Week in January. (It was Calvin Klein, but looked like the North Face thing students at my liberal New England college would throw on for a noon lecture — the one that announced: “I no longer care.”) There was Tremaine Emory, co-founder of art-music-fashion collective No Vacancy Inn, who has consulted for Kanye and spun alongside Virgil Abloh, taking a selfie in London designer Martine Rose’s Big Bird–esque poncho that same month. Actress and model Solveig Almaas smoking a cigarette and framing the logo on her fleece with a peace sign. Mister Mort — that menswear Punchinello — in a Mont Bell cap and Patagonia parody shirt. The newly prevailing spirit of cult Japanese menswear magazine Popeye. Drake performing in a Stone Island windbreaker at the Adult Swim upfronts just days ago (he’s a well-documented fan of the brand).

As winter has given way to spring, the idea has had surprising elasticity — down puffers and full-zip fleeces have become down and fleece vests, anoraks have shifted to long-sleeved tees and short-sleeved sweatshirts, Tevas with marled-wool socks are now Tevas worn barefoot. The cool kids aren’t letting this go; they all want to dress like they can tie a Yosemite bowline.

The look isn’t quite the “camping chic” that designers such as Givenchy, Lanvin, and — most notably — Prada sent down the runway. It’s not a hyper-elevated, high-fashion take on hiking clothes. Much of it is rather defiantly ugly, like something you’d buy (or exactly what you’d buy) at REI before a weekend in Phoenicia — practical, element-braving fleeces, ponchos, parkas, and windbreakers from no-nonsense brands like Patagonia, the North Face, Teva, Columbia, and Birkenstock. These clothes are paired with painter pants, Vans, Hawaiian shirts, and Dickies because head-to-toe outdoorwear would be too literal, of course — it has to be thrown off to communicate the wearer is in on the joke. The outfit isn’t designer, but it is fashion, in the way that any aesthetic executed with intentionality — ever insistent and dissonant — can become “a look.”

For 29-year-old multidisciplinary designer Justin Sloane, the clothes have an inconspicuous appeal. He’ll wear Patagonia jackets with Levi jeans and Converse or, now that it’s warm, Patagonia hiking shorts around the city. “I did grow up deep in that granola culture, but what I like about wearing these clothes is that you’re exempting yourself from fashion decisions. There’s something nice and anonymous about the pieces.”

I know, I know. It sounds like normcore, the now-three-year-old trend that rejected the consumerism of the early aughts by embracing blankness: stonewash jeans, plain cotton tees, white athletic socks. But where normcore idealized the Mall, indiscriminately incorporating bland stylistic totems across suburban categories — athleticwear as much as grunge as much as skate as much as prep — this new aesthetic worships the Woods, strictly defining itself by the idioms of hiking-camping-outdoor apparel. It telegraphs an enlightenment beyond urban, bourgeois concerns: I can survive perfectly fine outside of the city — and in style, thank you. Nike (or Adidas or New Balance for that matter) isn’t part of this. Converse isn’t part of this. Gap isn’t part of this. (Maybe Uniqlo, but only Heattech and only the puffers.) A successor to normcore (as is, arguably, athleisure), the look is normcore growing a SCOBY, carrying a backpacker’s trowel, and sporting an L.N.T. tattoo. It’s gorpcore.

“Listen, if you dropped me somewhere upstate, I’d cry,” says Mordechai Rubinstein (a.k.a., Mister Mort), “but I love clothes that can transport me. That’s what these clothes let me do — if they can withstand the actual outdoors, then I can wear them to go outside in Greenpoint.” Unlike Fashion Week facsimiles, the clothes have the cred of true outdoor gear; what makes them cooler, of course, is that they’re not trying to be cool. Their aesthetic is auxiliary to, well, survival. “I’ve never thought of it as a conscious style choice,” says Justin R. Saunders, the Montreal designer and blogger behind JJJJound, who mixes a lot of North Face and Patagonia pieces into his not-exactly-roughing-it wardrobe of Vans and A.P.C. jeans. “In Montreal, where the weather can be not so great, I’ve always found them to serve a utilitarian need — they’re warm and comfortable. Obviously the brands position themselves a certain way as great products without the flash. That’s what I like.”

“It’s definitely an extension of normcore,” says Lawrence Schlossman, brand director of high-end resale site Grailed. “But it’s also the shadow influence that Japanese designers have always had on American fashion. The influencers online — the guys who work with A$AP Mob and Luka Sabbat and Virgil — are dipped head-to-toe in Japanese brands like Needles, Nepenthes, Engineered Garments, Snow Peak, and Battenwear, which all do this normcore Patagonia thing, but a luxe, high-end version in better colorways and better materials. Then it trickles.” It’s not just Japanese brands that bestow prestige with the co-sign. American retailers like Pilgrim Surf Supply, Westerlind, and Hatchet Supply gobble up this geeked-out Japanese americana, which then adds to their own active-stoner cred. It’s — as ever — Supreme, too. “When a brand like Supreme works with the North Face on a collaboration, that’s powerful for North Face,” says Nick Paget, senior menswear editor at trend forecasting agency WGSN. “Same with Stone Island. Supreme knows the heritage and authenticity of the brands it partners with, and people listen to that.”

When high takes on low, as with Phoebe Philo’s take on Birkenstocks for Celine, Raf Simons x Stan Smith, or the Balenciaga appropriation of Bernie Sanders signage, the mashup confers a halo of prestige, like an ugly man who immediately becomes more interesting once he starts dating a beautiful woman: What does she see in him? That revered brands like Supreme and Engineered Garments and Nepenthes would deign to take on granola classics signals that there’s something worth paying attention to.

Schlossman himself has been a fairly reliable bellwether on the vagaries of fashion. In the past half-decade he’s moved swiftly from double monkstraps and Italian tailoring (“sprezzy” was a favored coinage) to sneakers and jeans (as editor of Complex-owned menswear site Four Pins). These days, Schlossman himself is feeling the camping-inflected look. “I’m not afraid to admit that I went out and got a Patagonia Snap-T this past fall because I saw Shia LaBeouf wear one over a hoodie and thought it was really cool.”

Gorpcore isn’t limited to men’s fashion (it was Phoebe Philo, after all, who resuscitated the Birkenstock at Céline in 2012), but for men, it does have a real-world, fashion-as-function appeal. Whereas a certain kind of woman wouldn’t blanche at having to buy $13 leather protectant for her $3,000 handbag, men — for the most part — are not such slaves to fashion. “Clothing that fits a purpose and does what it says will always be relevant to men,” says Paget. “In the U.K. [where Paget is based], men go to football games wearing Stone Island and C.P. Company to signal that they bought the right thing, paid quite a lot, but that most of all, the clothes will do what they’re supposed to do. Performance is paramount.” Sloane agrees that the clothes serve symbolic purpose more than, say, a Budweiser jacket or Nike hat does. “If you live somewhere like New York and like the idea of camping but only get to do it twice a year, wearing these clothes is a way of planting the flag that you’re into it even though you never get to do it.” Gorpcore, then, tags its wearer as seriously outdoorsy, the way that Timberland boots suggest a certain urban toughness or a Barbour jacket says, “I shoot pheasants for fun.”

Of course, there may be one other reason these clothes fit our current cultural mood. It’s an overreaching journalistic impulse to attribute every micro-phenomenon to post-election malaise, but the rise of gorpcore — which exalts activities that, in their environmental consciousness, have always been considered hippie-dippie or tree-hugging — is a political act. “It’s crunchy,” says Schlossman. “And in this political climate, these brands we’re talking about stand for good. I’ve not necessarily been someone to vote with his dollar, but it’s the perfect marriage of ideas.” Mother Nature has been how liberals — one famously — have been licking their wounds, and celebrating it is a rebuke of the president’s planned $1.5 billion cut from the Interior Department’s budget. To wear Patagonia is to stand in solidarity with the brand’s environmental advocacy. It’s no accident that Black Lives Matter activist DeRay McKesson has worn the same Patagonia vest for nearly a decade. Sporting brands that give voice to your value system is its own form of silent protest.

Ideas in fashion and food and design and travel don’t occur in isolation. You can trace the philosophical throughline — that maybe nature holds some secret to self-improvement or emotional deliverance — in the rise of grain bowls and Moon Dust, the comforting, naturalistic principles of hygge and lagom, and the Ranch. Gorpcore’s not fashion for the 1 in 7 billion, nor is it fashion for the one percent — it’s live-good, do-good, feel-good fashion for the ones who care just a little too much.