Three great friends — the actress Kirsten Dunst and Laura and Kate Mulleavy, the fashion-designing wonder siblings behind the craft-meets-high-fashion line Rodarte — are sitting in a booth at Smoke House, an old-school Hollywood place with red leather booths and headshots on the wall just across from the Warner Bros. lot in the valley. They are discussing Woodshock, a dreamy, trippy feature film — a meditation on grief, destruction, and psychedelic drugs — that will be released September 22. The movie was written and directed by the Mulleavys; Dunst served as an executive producer and the film’s star.

“We went on a trip to Florence together in about 2011,” Laura says. The sisters had already drafted a short version of a script, “and we drank so much limoncello and we started talking about it.”

“We’re all so emotionally interconnected,” Kate explains.

“I was the first actress to wear their clothes,” says Dunst. “It was while I was doing press for Spider-Man, and it was this black dress with chains that it turns out were sewn by their mother, and they sent me a box of trinkets — we were all just so excited.”

“Artistically, I think you just meet someone you’re supposed to work with,” Kate says. Both sisters are big talkers: articulate in describing their intentions and their art. Dunst is a bit more reserved. “Laura and I are a very internal network, so for me, writing a script, we didn’t talk to anyone about it,” says Kate. “So for us to sit down with Kirsten and say, ‘Let’s get through a really early state of something,’ that was a big deal.”

For the Mulleavys, film was an obvious extension of their art. “I kind of learned over the years that expression through clothing is just one way of telling a story,” says Laura, “and putting it into a film context is a narrative choice that you get to make. We were trained to study words and study imagery and to think about meanings that you can imbue in a story.” The idea was to make a film about Northern California, where the sisters grew up wandering in a redwood forest just outside Santa Cruz. The film would be about destruction — they’d spent their childhood fixated on the disappearing landscape, as well as the fate of the endangered California condor — and they imagined something set in the 19th century, where trees the size of skyscrapers were being felled every day and the vibrations were felt for miles.

But then there was the limoncello and a third person in what is typically for the sisters a two-person conversation. The notion of a film started to become real.

“At one point we said, ‘We’re going to make this a full film now, and it doesn’t need to be set in the 1800s,’ ” says Kate.

“I think that was my idea,” says Dunst. “I was like, ‘This doesn’t need to be period!’ ” (Later, the sisters say that they had been thinking along the same lines already.)

“And then one day Laura and I were in the car,” says Kate, “and we just turned to each other and said, ‘Theresa works in a pot shop.’ ”

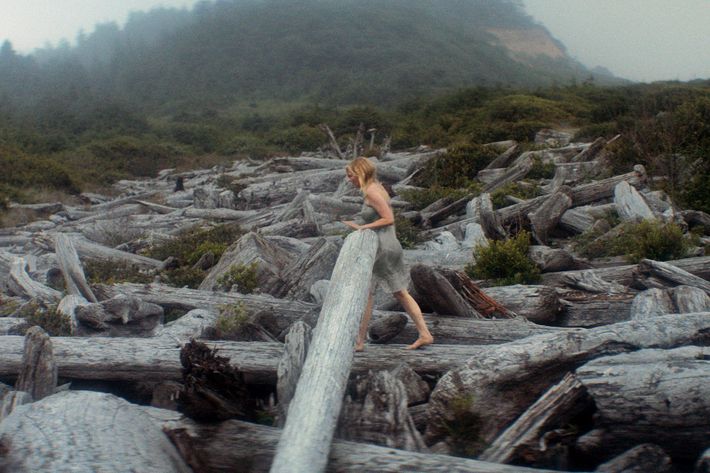

Theresa is the protagonist of Woodshock. She is a lonely woman — her mother dies in an early scene — struggling with her grief in a Humboldt County redwood home. She walks in the forest for solace, but the trees keep coming down — her boyfriend works as a logger. Theresa’s job as a clerk in the marijuana dispensary, which is seedy and neon-lit (in order to look, Laura says, a little bit like outer space), is a lot more complicated and treacherous than her sleepy eyes initially suggest. The action centers on the particularly potent strains of pot that have replaced lumber as Humboldt County’s most famous cash crop.

The movie won’t be surprising visually or vibe-wise for anyone who has observed the sisters’ fashion career: They’ve always been inspired by Northern California, and their work has always felt more rooted in a specific ethos than in a specific time. The ethos is New Age–y and Californian; a little bit Ladies of the Canyon and a little bit Stevie Nicks. It’s a West Coast fantasy for the rest of the world, away from the glitz of Hollywood but nevertheless connected. It is crafty and dreamy and impressionistic. The sisters became famous for dresses that would have worked well on wood nymphs, and the movie looks quite a lot of the time like a watercolor painting of the enchanted forest in a fairy tale.

“What is humanity capable of?” Kate asks. “That’s really the question. Beautiful things and destructive things.”

“We were really interested in understanding the psychology of destruction,” Laura says, “and saying, okay, if this is something that happens, and you’re living in a destructive time period and a destructive environment supported by extreme beauty, it’s about being either a very passive or a very active agent in that destruction. It’s about the psychology of violence.”

Rodarte’s fashion shows have been unusual in form (no straightforward runways, neon-light installations, models standing in unusual formations), and the Mulleavys’ filmmaking style is purposefully disorienting. They use mirror reflections and other, subtle displacements to keep its lush, extreme beauty from becoming some sort of bucolic, soothing travelogue. It was going to take a specific kind of actress to thrive in that setting, and Theresa was always only ever going to be played by Kirsten Dunst, who knows a thing or two about disorientation: When she made Drop Dead Gorgeous, Allison Janney told her that sometimes you’ve just got to spin around a bunch so that you’re super-dizzy when “action” is called. Dunst did that in this film. “Thinking about Kirsten,” Kate says, “well, there’s no one else that can do this. The thing I say about her, and I literally say this sentence all the time, is that she’s brilliant in Bring It On, and she’s brilliant in Melancholia, and I’m sorry, but let’s just stop and think about that for a second. People love it when you’re one thing. As a human being, when you defy being one thing, you will always have a trickier path.”

Dunst gives a little self-conscious chuckle and looks up through half-closed eyes. “Look,” she says, “I just want my picture on the Smoke House wall.”

In a lot of ways, the Mulleavys and Dunst are a natural creative match, occupying a similar mainstream-adjacent category. They are embraced by popular culture — by Vogue, by the Spider-Man franchise — but they have remained emphatically independent within it.

When Rodarte launched 11 years ago, it was almost immediately supported by the fashion Establishment. Their very first collection — ten dresses — was on the cover of WWD. What the sisters were doing was unusual: handmade, one-off things. And the story people told about them was enticing, too: these two sisters holed up in a cottage in the woods (they live in Pasadena, but whatever) and sewing long into the night, crocheting wild, witchy sweaters and cracked-out princess dresses that looked unlike anything else on the red carpet. They were both recent graduates of UC Berkeley, and they enjoyed steeping themselves in — and threading their interviews with — intense, thoughtful examinations of popular culture, literature, and art. After school, they didn’t move to New York or Milan or Paris; they stayed living with their parents for a while (they moved out eventually but still live together). When they describe their adolescence, it’s all about that forest, plus knowing who the best clerks were at their local Blockbuster. (Horror is one of their favorite genres.)

The rise of Rodarte corresponded with the rise of fast fashion, with the moment when the perfect cashmere crewneck became available at Uniqlo. What Rodarte offered was the opposite. There were never any basics apparent or available; Rodarte was about wearing original, one-of-a-kind things, the type of things that might look bananas to the uninitiated but spoke volumes in fashion language. They obsessed over handwork, over fantasy. Everything always felt like it had somehow crossed the membrane from a sort of shared sisterly dreamscape into reality. They’ve never sought straight-up direct success by translating their offbeat fame into expensive handbags or lipstick, offering a piece of the quirky dream at an affordable price (their father, a career botanist, is their CFO). The closest they’ve come is a line of less-expensive sweats marked RADARTE — clothes for crafting — and a one-season collaboration with Target. And they’ve always maintained low-key personas: They wear jeans, flat shoes, and plain blouses almost exclusively.

But the Mulleavys also have a knack for cultivating a certain type of celebrity: Dunst, for example, and Natalie Portman became both fans and friends, as did many key editors at Vogue. (When they did that line for Target, they launched it with a video starring Tavi Gevinson.) A quirky, slow-paced feature film was for them a far more obvious extension than, say, an affordable line of party frocks.

Dunst, in many ways, is the perfect companion for the sisters. She began working when she was 3 years old and became famous at 12, when she got a Golden Globe nomination for playing a bloodthirsty preteen who kisses Brad Pitt in Interview With the Vampire. There’s a certain magic to Dunst: She is tallish, blonde, and beautiful, but hers has never been a purely straightforward kind of beauty. She’s really good at playing crazy (Crazy/Beautiful) and suicidal (The Virgin Suicides), but she’s also great at being silly (Dick, Bring It On). There’s always been something bubbly about her, but the bubbles can be dark. She’s been open about her treatment for depression — she sought help in 2008 — acknowledging that being a Hollywood actress involves pressures that are “totally ridiculous.” She’s walked a fascinating line between mainstream and independent — her second-most famous onscreen kiss was delivered to an upside-down Tobey Maguire in the rain during her stint as a blockbuster love interest, but then she made Melancholia with Lars von Trier. She’s been the star of three Sofia Coppola movies. She’s undoubtedly an A-list celebrity, but she’s maintained a sheen of credibility, or a sense of an authentic attachment in her work — however you want to think of it — and she’s become something of a Hollywood cult hero as a result. The tundra faced by many Hollywood women when they reach her age — which is 35 — doesn’t seem to be slowing her down. In addition to Woodshock, in the last few years she shot Fargo and The Beguiled. Much like the Mulleavys, her position in the West Coast alterna-world is an asset, allowing her to create her own path through the world of shrinking options and plastic surgery, to take some time to make this tiny, esoteric film about sadness and psychedelia.

Dunst has always been a very physical actress — in his 2001 New Yorker review of Crazy/Beautiful, the critic David Denby wrote that “the movie belongs to 19-year-old Kirsten Dunst, who wears stressed jeans and little tops that terminate five inches above her navel. I doubt that any performer has got so much out of an exposed belly since Hedy Lamarr in Samson and Delilah. Swiveling, jackknifing, raising her arms, and then crumpling over, Dunst has as much intensity as a Martha Graham dancer. When her face falls in alcoholic dismay, she can look like a drowned cat.” And it’s that flexibility, that notion that her emotions are just so close to the surface that they can’t help but bubble up, that makes her so watchable. Dunst has never been afraid to be vulnerable.

“People tend to put people in boxes,” she says, “and that’s always been very uncomfortable for me. I don’t think I have a box, and I feel like that’s confusing people. When I was in my 20s, I did Spider-Man, and that afforded me the luxury of doing what I wanted, doing indies and things like that. I think you have to figure out what artists you want to collaborate with, and that’s what’s exciting to me. I say no all the time, and it’s hard. Sometimes it’s like, Should I be doing this? But I think what you pick taste-wise ends up being the community that responds to you and will continue working with you, so …”

“It’s a big conundrum,” says Kate, nodding sympathetically at her friend. She can relate. “Obviously, we have not become the kind of designers who are doing it for the glamorous lifestyle or to sell a thousand handbags. We sell a few dresses, and that’s the truth. We’re creative. Some people like us for that, and some people don’t.”

“We have a rule with ourselves, all of us,” says Laura. “We have this fake bookshelf that we’re all building together over time, with things that we contribute. We really want everything that goes on it to be valuable, to really believe in the things that go on. Kirsten won’t do things she doesn’t think are good.”

One of the things the women did together to prepare for the movie was to spend some time with Dolly, a California condor that lives in the Los Angeles zoo. The Mulleavys had always been interested in their plight (“It’s what we gave our quarters for in the cafeteria at school,” Laura explains), and they wanted Dunst to see what they were talking about. Dunst hugged the mammoth redwoods, of course, standing beneath them and feeling like a tiny, insignificant piece of sand. But there was also this bird. So much of the world is disappearing, and here was something beautiful that they could see. Dunst scrolls through her phone looking for a photo she snapped of Dolly in profile. Here it is: She looks like Alexander Hamilton on the $10 bill. “She’s like 1,000 grandmothers all looking at you at the same time,” Laura says. “She’s so wise.”

They are all nodding vigorously in agreement, about Dolly, about redwoods, about Hollywood, about fame, about the quirky sorority the three have found together.

“For whatever reason,” Dunst says, “we just make things together.”

“To work with someone who understands your language so well that you don’t even have to speak, that’s the best thing you could ever ask for,” says Kate.

“The thing about making this film is that it’s just like making our family bigger,” says Laura. “She’s family now.”

Styling by Rebecca Ramsey, hair for Dunst by Suave Professionals Celebrity Stylist Jenny Cho, makeup for Dunst by Fiona Stiles using Fiona Stiles Beauty at Starworks Artists, hair for the Mulleavys by Cervando Maldonado, makeup for the Mulleavys by Uzo using Nars Cosmetics @VisionNationArtists.

*This article appears in the August 7, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.