In 1970, Kate Millett became the reluctant face of the women’s liberation movement with the publication of her book Sexual Politics. A portrait of her graced the cover of Time magazine, and the media dubbed Millett the Karl Marx and the Mao Tse-Tung of women’s liberation. By the time she died this week, at age 82 while on vacation with her wife, she had become a kind of cultural ghost. Millett spent the last 47 years writing books, teaching, and engaging in political activism, yet her role as one of the founding theorists of the modern women’s movement had faded into the historical background.

In her introduction to a paperback edition of Sexual Politics published by University of Illinois Press in 2000, Millett complained that she’d had a hard time getting her book back in print, even though original publisher Doubleday deemed it one of the ten most important books they published in the 20th century. “My ‘feminist classic’ had become a radical text, dubious, far out, a risky proposition,” she wrote.

Sexual Politics was always a radical text and a risky proposition, though. Pulsing with righteous fury and scathing humor, it used close literary analysis of four male writers (Henry Miller, Norman Mailer, D.H. Lawrence and Jean Genet) to explore how the patriarchy rules our lives and insinuates itself into our imaginations. Calling her book a mutant genre, Millett declared that “the adventure of literary criticism is not restricted to a dutiful round of adulation, but is capable of seizing up on the larger insights which literature affords into the life it describes, or interprets, or even distorts.”

Millett’s approach now looks like an early model for a certain kind of contemporary hot take, in which a pop cultural text is analyzed for its sexist/racist/cis-normative assumptions. In Sexual Politics, she reviled Henry Miller’s habit of referring to women as if they were a sum of their sexual parts (all “haunches” and “huge teats”) and zinged Norman Mailer as a “prisoner of the virility cult” whose “powerful intellectual comprehension of what is most dangerous in the masculine sensibility is exceeded only by his attachment to the malaise.” [p. 314] As for D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, she dryly noted that “the celebration of sexual passion for which the book is so renowned is largely a celebration of the penis of Oliver Mellors,” the “lover” of the title. [p. 238]

Although this hybrid form of criticism was Millett’s own invention, Sexual Politics didn’t emerge out of a vacuum. She drew inspiration from the budding women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s, attending meetings of New York Radical Women, a Manhattan group that included feminist pioneers Shulamith Firestone, Robin Morgan and Kathie Sarachild. A 35-year-old sculptor and grad student, Millett was fired from her teaching job at Barnard College in 1968 and decided to use the free time to turn her doctoral dissertation idea into a book.

“As the book took shape, so did events …” Millett later wrote. “By the summer of 1970, at the moment this text was released, there was a great wave of feminism building. It was the 50th anniversary of the suffrage, there were marches and strikes of women workers in New York and throughout the United States. It was the right moment.”

It’s hard now to imagine that a book of literary criticism could have such a convulsive effect on American culture, but Sexual Politics did. New York Times book critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt penned not one, but two reviews. “[T]he book is supremely entertaining to read,” he raved, not to mention “breathtaking in its command of history and literature … and written with such fierce intensity that all vestiges of male chauvinism ought by rights to melt and drip away like so much fat in the flame of a blow torch.”

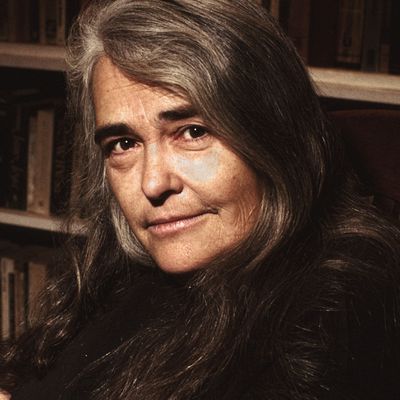

Besieged by interview requests, Millett agreed to speak to Time magazine for a special issue about the women’s movement but declined to be photographed for the cover; her new celebrity status was already causing hard feelings among her fellow radicals. Tricky Time put her on the cover anyway (using a portrait painted by Alice Neel). Suddenly she was the figurehead of feminism, her book a national bestseller. She found it excruciating.

“Has anyone ever gone mad from media before?” Millett asked in Flying, her 1974 memoir chronicling the chaotic aftermath of Sexual Politics. She withered under the pressure of touring and schadenfreude. Norman Mailer wrote a savage essay in response to her book and invited her to publicly debate him; she refused. (Germaine Greer, Jacqueline Ceballos, Jill Johnston and Diana Trilling took him on instead, an event captured in the documentary Town Bloody Hall.) Millett funded a Women’s Liberation Cinema collective as a way to “guard against ego-tripping, multiply my accidental good fortune, share it, make something for all women” but sisterhood turned out to be painful as well as powerful. Millett wrote that her movie collective dream turned nightmarish, with “a nest of oppressed women screaming at me like machine guns.”

Her sexual orientation also became a matter of public debate. Millett, who was then married to a man, but also slept with women, was quoted (or misquoted) in a magazine distancing herself from lesbianism. At a large public event, activists prodded her to confess her sexuality. “That word in public, the word I waited half a lifetime to hear. Finally I am accused,” she writes in Flying, recalling that bisexuality at that time was considered a cop-out. “Yes I said yes I am a lesbian. It was the last strength I had.”

Although Millett’s public persona waned, she never disappeared from view. She wrote more books — including Sita, which detailed her love affair with an older woman, and The Loony Bin Trip, a chronicle of mental breakdown in which Millett (who rejected the diagnosis of bipolar disorder) frames psychiatry as “a terrifying form of social control”— and founded a women’s art colony in upstate New York. Her flavor of second-wave feminism came to seem outdated for a while: too strident, too angry. But stridency and anger are sounding pretty useful nowadays, and besides, the overhaul of patriarchy she called for 47 years ago never exactly came to pass.

Millett knew that it might take a while. “[T]he history of the emancipation of women is — like other stories that describe the long, difficult winding down of oppressive systems — circular; a little forward, almost as much backward, then standstill, reaction, repression, then another surge,” she wrote in 1990, adding, “If it isn’t easy, it’s always interesting. And the work of enlarging human freedom is such nice work we are lucky to get it.”