To be a New Yorker is to confront daily evidence that everything you love will one day be destroyed: Favorite neighborhood spots — even entire neighborhoods — are razed to make way for fancier, less soulful versions of themselves. So it was last week, when the American Museum of Natural History closed the Harry Frank Guggenheim Hall of Minerals and the Morgan Memorial Gem Hall for a complete redesign after 40 years, erasing the dimly lit rooms that were the hushed temples of many a New York childhood, including my own. The replacement of the cavelike Hall of Gems with a bright Apple-store-like gallery seems to have hit particularly hard among many who grew up in ’80s New York, when the galleries were new and the carpet fresh. Posts about the closing on social media were greeted with lamentations and memories; the Instagram hashtag #hallofgems collected emotional thank-you notes, with fans in prayerful postures in the quiet rooms and children encountering geodes ensconced in wall-to-wall carpeting one last time. (An online petition has been started in a last-ditch effort to save the doomed hall, but like other attempts to halt New York change, it is almost certainly a lost cause.)

“The reason I’ve always loved the Hall of Gems so much is because as far as public spaces in New York go, it really catered to sensitive people,” said Scotlan Goldbeck, who took refuge in the Hall during a difficult time in high school and had her first date with her husband there. “The city is so loud and intense and this was a reprieve from that.” Even to young children, the Hall didn’t feel like a hall, but a secret cavern set apart from the rest of the museum.

“As a kid, you’d go to all these other spaces in the museum and get sensory overload, but then end your trip in this quiet mysterious place where you’d come down after the blue whale high,” said Amy Boyle, my sister, now a museum educator with whom I spent many Sundays at the Natural History Museum guided by our father, who had a special fondness for the Hall. Ending in the peaceful rooms was clearly a tactic employed by many parents exhausted from chasing kids hyped up on dinosaur bones and sugary Astronaut Ice Cream.

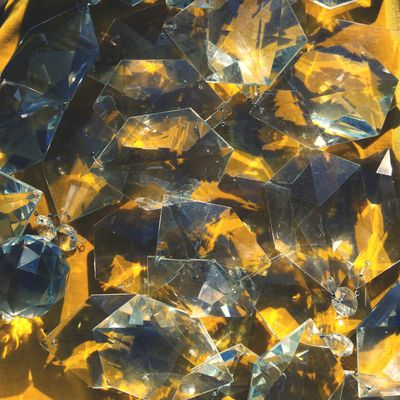

Exploring the Hall’s concentric circles and hidden passageways felt both like a journey into the center of the Earth where the gems were born and like stepping onto a spaceship, perfect for viewing the meteorites. Being a little girl in the 80’s meant being surrounded by glitter—it was the era of the Bedazzler, of the gemstone in the middle of She-Ra’s golden belt, and glitter pens, after all–but the Hall defamiliarized the stones, making you take them in as objects miraculously formed by nature instead of just cool shiny things Jem and the Holograms might wear. “For a kid who grew up on shows like Fraggle Rock, the gems and minerals seemed like relics from some fictional, magical world, beautiful and a little scary,” says Sasha Sagan, who used to visit the museum with her father, the astrophysicist Carl Sagan.

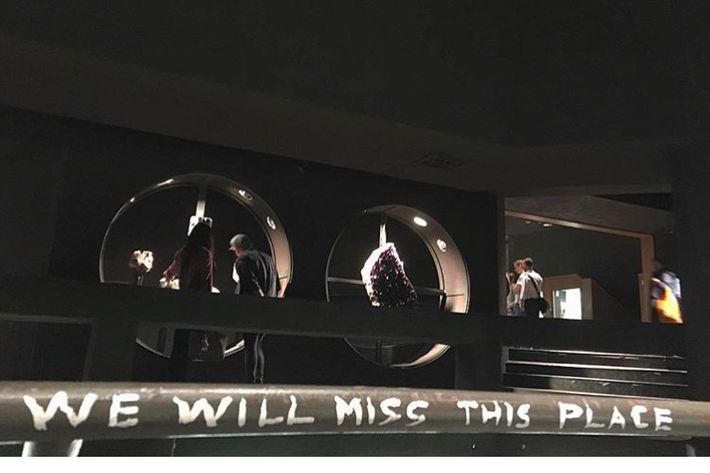

Exhibited in lit vitrines and mounted in circular portals, the gems and minerals “really stood out so you looked at them for their aesthetic qualities, not just for the interpretive materials teaching you the science or distracting interactive computer screens,” said my sister, the museum educator. “It made the experience of going through the exhibit a lot about close-looking and observation, which are important skills I try to teach kids on museum visits.” Its hidden passageways and alcoves allowed you to have alone time with the gems as a kid, giving you opportunities for introspection as well as for hide-and-seek, or just rolling around on the carpet until your hair stood on end from the static.

Games of hide-and-seek weren’t the only non-science-related activities the unusual space inspired. “I wanted to get married there when I was a child,” said artist Amy Beecher. “There’s a sort of radial set up to the room, that big gem in the middle was basically a topper on a giant, carpeted wedding cake, which seemed the ideal architecture for some sort of romantic ritual. And since weddings are about love and also, it seemed at the time, pretending to be a princess, the gem room really fit the bill.”

Visiting on the Hall’s last day on Wednesday, my sister found the atmosphere of the Hall was less like a science exhibit than a wake. “A lot of people seemed to be in mourning for the space, lost in their own memories,” she said. “I saw one other person crying a little bit. A lot of people around our age were wandering through the space alone, taking a lot of photos, quiet. I heard a lot of guards and museum staff coming in, saying, ‘I’m just coming down to pay my respects.’ I was very emotional myself because we spent so much time there with our father.” He died in 2006.

One lifelong New Yorker in her 30s had a similar moment in her final pilgrimage. “My mother used to take me to the gem room every day after nursery school, and its serene vitrines and carpeted embrace are intertwined with my memory of her,” she told me. She ended up going back twice before it closed, changing travel plans to return. On her last visit, the Saturday before closing, she asked a guard to take her picture. “She said she wasn’t allowed to do that but she saw how heartbroken I was and listened as I told her my story. I got very emotional and started to leave the museum — but once I got as far as Lucy the Australopithecus, I had to go back.” The guard accompanied her to her favorite room, so that she wouldn’t be alone there.

“’I want a piece of that carpet,’” she remembers telling the guard. “She said, ‘Trust me, you don’t want it, it’s disgusting’ — but said if she could save me some, she would.’”

Still, others spotted jagged areas of carpet missing from the walls; unlike the burglars in the famous 1964 heist who stole the Star of India sapphire from the museum, these thieves just wanted a piece of dirty fabric, a souvenir from a peaceful place in a chaotic world. “There was something spiritual about that room, about those gems and the way they were displayed,” Scotlan Goldbeck mused. “It really felt like the gems were being honored.” From the comments on the petition and social media, and from the people I had crying on the phone to me during conversations about it, it is clear that many felt the same about the gloriously carpeted hall. “It is no surprise that people feel a sacredness about the Hall of Gems,” remarked Kathleen Moore, a divinity student. “That’s what ‘sacred spaces’ ought to be — places set apart from the everyday world that, through quiet and beauty, can move our brains into that contemplative space. Especially in the age of the ever-present smartphone and the need to be constantly on call, it is rare to find a space that asks us to put those things down for a moment, take a breath, and just watch some pretty things sparkle.”