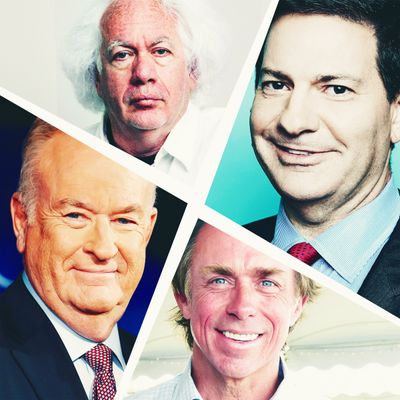

And the stories keep on coming: about how political pundit Mark Halperin rubbed his erect penis against younger female colleagues (a claim he denies); how Artforum co-publisher Knight Landesman touched young female employees against their will and told one of them that she needed to be “more open to physical contact to succeed”; how Amazon Studios head Roy Price propositioned a producer, assuring her, “You will love my dick”; about New Orleans restaurateur John Besh, whose organization is alleged to have been a hotbed of harassment; about Ben Affleck, who groped women in public; about New Republic literary editor Leon Wieseltier, who’s reported to have thanked a young colleague for wearing a miniskirt to work.

All these variations, all these stories … I’m so tired. Tired of getting — or hearing about other women getting — grabbed or pinched or demeaned, tired of having had to laugh. I’m tired of feeling paralyzed, unable to confront friends and colleagues about what they just said or did, because we know being the scold is its own form of self-exile, of exposure and vulnerability, of risk. If this were a feminist mini-series, gorgeously shot, with a tidy narrative, this beat — the outpouring of stories and memories we didn’t even know we’d repressed — would be wrapping up, and we’d be moving on to the denouement. But there is no sign of a pause; there are indications that it is just beginning.

In hearing these individual tales, we’re not only learning about individual trespasses but for the first time getting a view of the matrix in which we’ve all been living: We see that the men who have had the power to abuse women’s bodies and psyches throughout their careers are in many cases also the ones in charge of our political and cultural stories.

The media is breaking the news here; the media is also deeply implicated in this news and still shaping how the tale is getting told. Ours is an industry, like so many others, dominated by white men at the top; they have made the decisions about what to cover and how, and they still do. The pervasiveness of these power imbalances and the way they affect how even this story itself is being told are instructive. Here is something you should know, from inside a publication: For every one of these stories of harassment and predation finally seeing the light of day, reporters are hearing dozens more that will not be published, because women won’t go on the record in an industry still run by the people they want to name, or because the men in question aren’t powerful enough to interest those who are powerful enough to decide what has news value, or because the damage these men are alleged to have done seems insignificant on a scale that has recently been drawn to accommodate the trespasses of Harvey Weinstein, and of writer-director James Toback, named by more than 300 women (whose accounts he denies).

The accused are men who help to determine what art gets seen and appreciated — and, crucially, paid for. They decide whose stories get brought to screens: There is currently a campaign pointing out that Amazon under Price canceled the proto-feminist show Good Girls Revolt, in addition to passing on The Handmaid’s Tale and Big Little Lies. These decisions matter; they shape what kinds of messages audiences receive and what kinds of characters they are exposed to.

They are also the men with the most power to determine what messages get sent about politicians to a country that then chooses between those politicians in elections. Mark Halperin co-authored Game Change, the soapy account of the 2008 election (excerpted in this magazine), which featured all kinds of history-making candidates who were not powerful white men. Halperin’s view of Hillary Clinton in particular was two-dimensional: Through his lens, she was a grasping and scandal-plagued woman; her exaggerated misdeeds and the intense feelings she engendered were all part of propelling his profitable narrative forward. His coverage of Trump, meanwhile, in this last campaign cycle, was notably soft, even admiring: Halperin once argued that the sexual-assault claims leveled at Trump would only help the now-president’s brand.

Yet his view of the history we’ve just lived through was the one that was amplified and well compensated; there was not just the book deal but Showtime and HBO deals, too, and a regular perch on Morning Joe.

(HBO, Penguin, and NBC have dropped him.) The same power that afforded Halperin the ability to allegedly rub up against younger colleagues — colleagues who shared stories with one another but never felt they had enough power to file a formal complaint at ABC, where he held so much sway — also meant that he got to shape the nation’s view of a woman whose political story had already been shaped by other men who abused their power, including her husband and her 2016 opponent Donald Trump, not to mention Anthony Weiner. Lots of people still strain against the argument that gendered power structures helped determine Hillary Clinton’s (and thus our nation’s) fate, but when they do they are too often thinking of gender as an attribute that belongs only to her, the woman, and not to the men whose gender-afforded power ensured that she would have to work around and against so many dicks — by which I mean literal penises — in her efforts to become the first woman president.

It matters, in a far less commercial way, that Leon Wieseltier, former literary editor of The New Republic — where I worked for nearly two years, though never with him — was a powerful boss and feared force within his highbrow institution; he shaped the worldview of generations of journalists at what used to be called, self-congratulatingly, the in-flight magazine of Air Force One. And it matters that he also happened to kiss women subordinates against their will and comment on the bodies and clothing of his young female colleagues. And, according to colleagues who spoke to Splinter News this week, to spend vast portions of editorial meetings criticizing women — including Clinton and Nora Ephron — he thought were stupid yet who had somehow managed to get far in life. It is a rich irony, perhaps lost on Wieseltier, that the history of America has been one of wholly mediocre white men wielding unearned influence, often building their power by stoking resentments against non–white men via belittlement, vilification, and derision. Wieseltier’s magazine did just this on an editorial level, famously endorsing Bill Clinton’s welfare reform by deploying a cover image of a black mother smoking a cigarette.

Then, of course, there are Roger Ailes and Bill O’Reilly, men whose work to bolster the white-male power structure was always direct. Through Fox News, they worked to promote a Republican Party bent on reinforcing the power imbalances that left men like them in charge of television networks and as anchors of television shows, and so powerful and so rich that years of complaints of direct harassment and abuse could land, get muffled, or be settled and paid off with barely a hitch. That both men finally lost their jobs, and that Ailes is now dead, offers little relief; the party and candidate they labored to create and sell to America are now in power.

And while it may feel cathartic for some women to finally get to say things they’ve been waiting years to say, this does not undo the damage. We can’t go back in time and have the story of Hillary Clinton written by people who have not been accused of pressing their erections into the shoulders of young women who worked for them.

We cannot retroactively resituate the women who left jobs, who left their whole careers because the navigation of the risks, these daily diminutions and abuses, drove them out. Nor can we retroactively see the movies they would have made or the art they would have promoted, or read the news as they might have reported it.

This tsunami of stories doesn’t just reveal the way that men have grabbed and rubbed and punished and shamed women; it shows us that they did it all while building the very world in which we still have to live.

*This article appears in the October 30, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.