In celebration of New York Magazine’s 50th anniversary, this weekly series, which will continue through October 2018, tells the stories behind key moments that shaped the city’s culture.

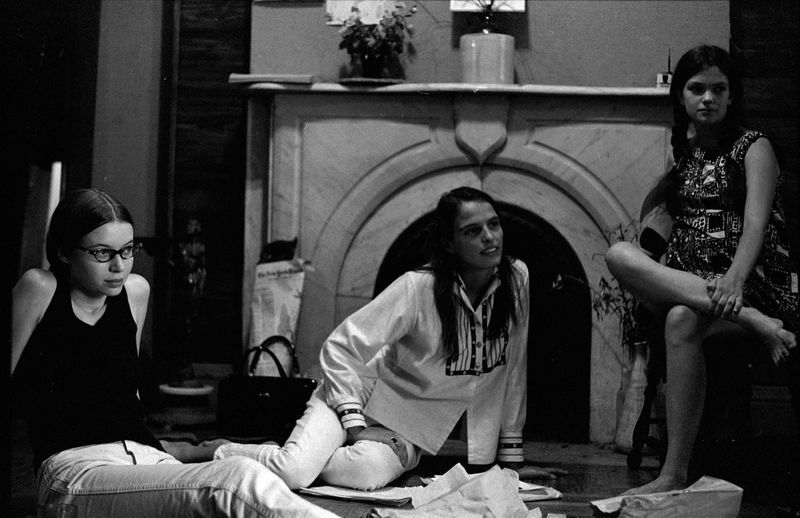

In the fall of 1967, a small gang of women began meeting regularly in cramped apartments across the Lower East Side. At the time, the Civil Rights Movement was shifting toward Black Power, while resistance to the Vietnam War continued to escalate. These women, mostly in their 20s, had caught the scent of revolution in the air. Their group, New York Radical Women, disintegrated within a few years, but during its short, fractious life, it helped define the burgeoning women’s movement and pioneered crucial elements of modern feminism. It arose out of a savagely polarized political moment, much like our current one, in which the frustrations and injustices of life as a woman suddenly exploded into eloquent rage.

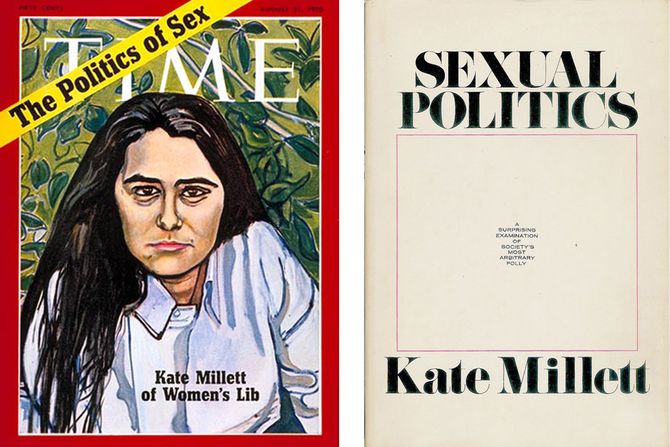

These radical women coined concepts and slogans like consciousness-raising, “sisterhood is powerful,” and “the personal is political.” They wrote formative essays and books about sex and gender roles and misogyny that laid the foundation for women’s studies: Anne Koedt’s “The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm,” Pat Mainardi’s “The Politics of Housework,” Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, Carol Hanisch’s “The Personal Is Political,” Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will. (Some of these groundbreaking works debuted in the group’s mimeographed spring 1968 pamphlet, Notes From the First Year, and its sequel, Notes from the Second Year.)

NYRW also practiced a flamboyant brand of political theater, most infamously with their 1968 protest of the Miss America pageant, which inspired the myth of feminists as bra-burners. Even if few of the pussy-hat-wearing protesters at January’s Women’s March know their names, the influence of New York Radical Women reverberates through the carnivalesque spirit of contemporary feminist activism.

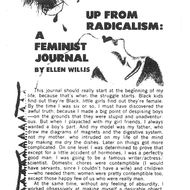

The group started out with a dozen or so women and grew exponentially by word of mouth; no one kept a tally of the fluctuating membership, but several hundred women were showing up to meetings by the time NYRW disbanded. Some members came from academia or journalism: Peggy Dobbins was a sociologist, Carol Hanisch a journalist, Bev Grant an alternative-press photographer. Some had been inspired by the counterculture: Kathy Barrett belonged to guerrilla theater troupe Pageant Players, while Robin Morgan ran with the Yippies. Others, like Judith Duffett and Alix Kates Shulman, were itching to break loose from their lot as housewives. NYRW members went on to be major figures in second-wave feminism, as writers, thinkers, and activists. Rosalyn Baxandall, for instance, created the first feminist day-care center, Liberation Nursery, and became a historian of women’s lives. Ellen Willis was The New Yorker’s first pop-music critic and later co-founded NYU’s Cultural Reporting and Criticism program.

Many had been radicalized by their involvement in the civil-rights and anti-Vietnam struggles, while also feeling increasingly alienated by condescending attitudes toward women within the left (especially after Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader Stokely Carmichael’s infamous quip, “What is the position of women in SNCC? The position of women in SNCC is prone.”)

Fifty years later, memories have eroded but the sting of ancient friction remains. Bitter battles were waged over whether women should work with men on the left or forge a separatist route; over whether to focus on theory or action; over who should speak for the movement. Members soon splintered off into vital subgroups like W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell) and Redstockings, and later some would regroup under the name New York Radical Feminists. But many inspiring figures and larger-than-life characters contributed to the supernova that was New York Radical Women. Here they tell the story of the group’s formation and impact.

Becoming ‘Radical’ Women

In cities across America, newly politicized women began creating women’s caucuses within left-wing organizations and comparing notes in casual get-togethers. In New Orleans, sociology grad student Peggy Dobbins helped launch a group to talk about women’s history and experiences. In Chicago, Jo Freeman and a 22-year-old painter and burgeoning revolutionary, Shulamith “Shulie” Firestone, instigated a similar gathering. When Firestone moved to Manhattan, she met Chude Pamela Allen, a foster-care worker, civil-rights activist, and the wife of prominent black journalist Robert Allen. They quickly called a meeting of about a dozen women at Allen’s East 3rd Street apartment for November 1967, recruiting “whoever was interested in starting an independent Women’s Liberation Movement.” They would soon be joined by women like stay-at-home mom Alix Kates Shulman and civil-rights activist Kathie Sarachild.

Peggy Dobbins: We were sitting in the kitchen and Pam’s husband was there. We said, “Oh, Bob, you can’t stay!” We cited the fact that whites couldn’t stay in Black Power meetings so men couldn’t stay in ours. This was just going to be women! I remember at the first meeting Anne Koedt sharpened our focus to: Were we radical women or women radicals? Were we women who were engaged in radical causes, or were we radical about the way women were treated?

Kathie Sarachild: Back then there were enormous struggles over what words to use. I was afraid that the word radical would frighten people away. I guess it was the spirit of the time that it actually attracted them.

Alix Kates Shulman: I was home in Manhattan with my children when I heard these women on the radio talking about [NYRW and] this thing they called women’s liberation. I was a perfect specimen of who they were trying to reach: a genuine housewife. I’d had to leave my job as an encyclopedia editor when I got pregnant, because back then there was no maternity leave. The thing that was so shocking to me was that these women were talking with authority about politics -— I’d only heard men talk that way.

Judith Weston (then known as Judith Duffett): These women had all come from the civil-rights movement and I hadn’t. I hadn’t done anything political before. I thought they were stunning — so strong and militant and certain. I remember Shulie [Firestone] talking about how women won’t be liberated until they can have babies outside the womb and I thought: That is pretty radical. But it was all on the table and we discussed it seriously.

The First Action

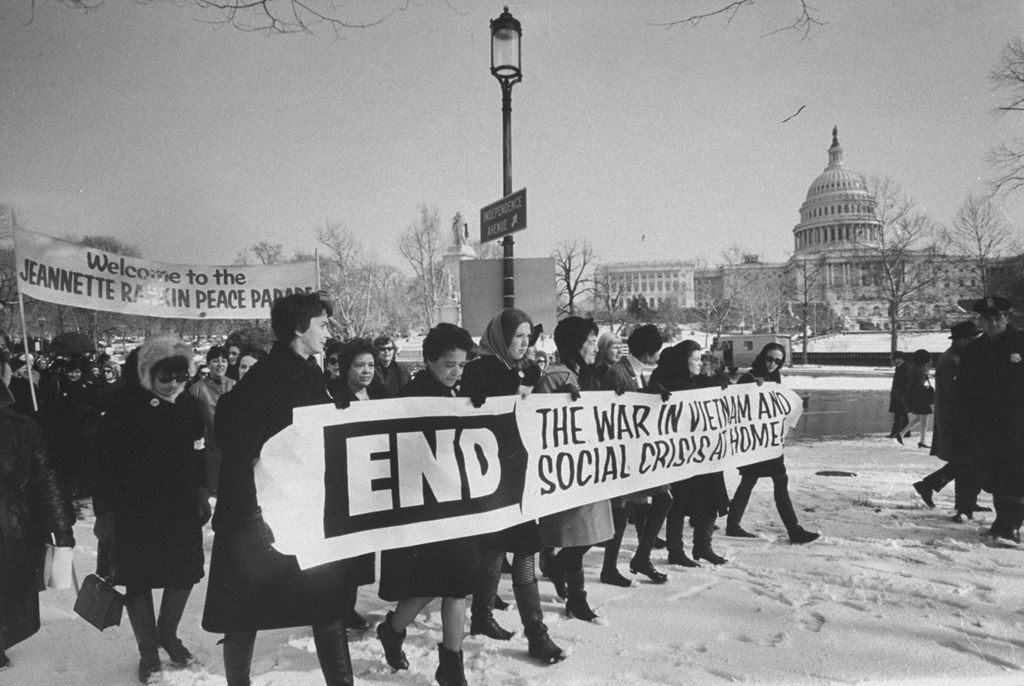

New York Radical Women announced their existence with a disruptive appearance at a January 15, 1968, women’s anti–Vietnam War march in Washington, D.C. Called the Jeannette Rankin Brigade, the march’s name came from the first woman ever elected to Congress, a pacifist. NYRW carried banners with slogans like, “Don’t cry: Resist,” and invited attendees to join them in burying passive female roles with a theatrical funeral service, complete with a coffin and a blonde effigy meant to represent traditional womanhood.

Sarachild: They were talking about a guerrilla theater action to try to get anti-war women to start addressing actual women’s-rights issues rather than being stereotypical “women for peace.” I wasn’t crazy about the idea but I brought some ideas people liked, so I was chosen to give the New York group’s speech [and write a leaflet], which read:

TRADITIONAL WOMANHOOD IS DEAD.

TRADITIONAL WOMEN WERE BEAUTIFUL … BUT REALLY POWERLESS.

“UPPITY” WOMEN WERE EVEN MORE BEAUTIFUL … BUT STILL POWERLESS.

SISTERHOOD IS POWERFUL!

HUMANHOOD THE ULTIMATE!

Sarachild: “Sisterhood is powerful” was a combination of black power and union organizing.

Carol Hanisch: I took that phrase off her leaflet and I started signing all my letters “Sisterhood is powerful.” But it got turned on its head along the way. Originally it meant that we needed to unite in order to win things for women. Later it got to be that you should be nice to all women. People would accuse others of being unsisterly if they criticized anybody.

Shulamith Firestone (from “The Jeannette Rankin Brigade: Woman Power?” in NYRW publication Notes From the First Year): It is naive to believe that women who are not politically seen, heard, or represented in this country could change the course of a war by simply appealing to the better natures of congressmen … The women at the Jeannette Rankin march were united only in their frustration … They were all keenly disappointed, and fully aware of their impotence.

Hanisch: We met radical women from other cities at the Jeannette Rankin protest. Although we weren’t all in agreement about where we wanted to go or how to get there, we were encouraged to find others ready to take our oppression seriously and do something about it.

Sarachild: Gerda Lerner, a historian of an older generation, told me she heard my speech with interest but she thought we were making the same mistake as the early feminists of the 19th century, which was to be too anti-man. Yeah, right.

What Should ‘Radical Women’ Do?

From the start, NYRW members saw the sharing of personal experiences as a strategy to expose all the invisible ways women as a group were oppressed — to unleash all their suppressed shame and resentment, and to begin to articulate the social and economic structures that kept them in their place in an era when marital rape was legal, a woman could not apply for a credit card on her own, and the term “sexual harassment” did not yet exist.

Hanisch: We came back [to New York] from Jeannette Rankin and continued to debate what to do. Would we do actions? Would we have a study group? Would we talk about our lives, like the idea of “tell it like it is” from the civil-rights movement, and “speak bitterness” as they did in the Chinese Revolution?

Sarachild: One of the women in the group, Anne Forer, said, “I think we have to do more about raising consciousness …. I’ve been thinking that men don’t find the real selves of women attractive. I’ve been thinking about all the false things we have to do to make ourselves attractive, even going blind and not wearing glasses.” It sounded like the kind of language we could reach millions with — and it reached me too!

Chude Pamela Allen: The topic I remember being personally profound was relationships to men. Somebody was commenting about her boyfriend saying something to her and everybody in the room went: “Oh, my god. That’s exactly what mine says to me.” If women are all being accused of being too emotional, what does that mean? If people who are powerless are trying to be heard and respected, it can push you into being a little hysterical, right?

Dobbins: By sharing personal experiences we were discovering that we weren’t crazy. We began to evolve a structure in which we went around the room and took turns speaking. Kathie Sarachild introduced as a discipline that you weren’t supposed to generalize unless you preceded it with a personal experience.

Sarachild: When women’s liberation started there was this myth of the emancipated American woman. Supposedly we were emancipated by the vote, so what did we have to complain about? We had to show that there were all of these economic and social pressures on us, causing us to falsify ourselves.

Robin Morgan: We were talking about sex one night. I admitted that on occasion in my marriage I had faked an orgasm. I was convinced that I was the only person in the world sick and perverse enough to have done this. Every woman in the room said, “Oh, you too?” It was an amazing moment.

Weston: My husband and I lived in this really small but expensive apartment on East 30th Street. At meetings I would say, “If anybody hears of an apartment let me know.” One day Cynthia Funk said, “There’s a place next door to me, maybe it would be good for you and Leonard — or just you.” She had picked up on the negative things I’d said about him … I went to see the apartment and then packed up my things. The whole point of consciousness-raising was if you said something, it changed everything.

Hanisch: A lot of left men didn’t like consciousness-raising because they suspected we were talking about all the bad things they did to women. Which was absolutely true.

Anne Koedt (from “The Myth of Vaginal Orgasm” essay in Notes From the First Year): Frigidity has generally been defined by men as the failure of women to have vaginal orgasms. Actually, the vagina is not a highly sensitive area and is not physiologically constructed to achieve orgasm … Women have thus been defined sexually in terms of what pleases men; our own biology has not been properly analyzed.

Weston: Anne presented “The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm” to us and we all went, whoa! But some people thought however true the essay might be, it was not a good organizing tool. It didn’t address economic issues, it didn’t address domestic equality — and it would certainly alienate men. There was a lot of discussion of how to bring the men along too.

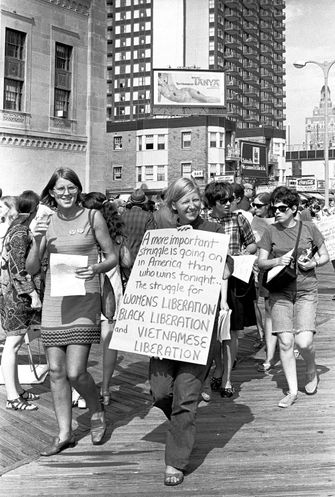

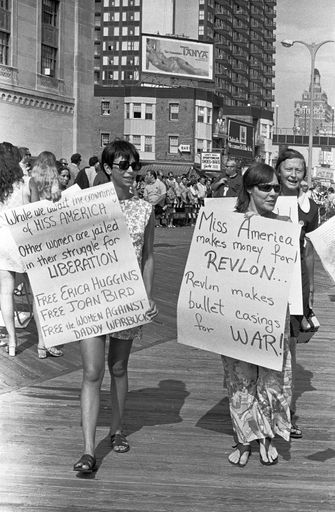

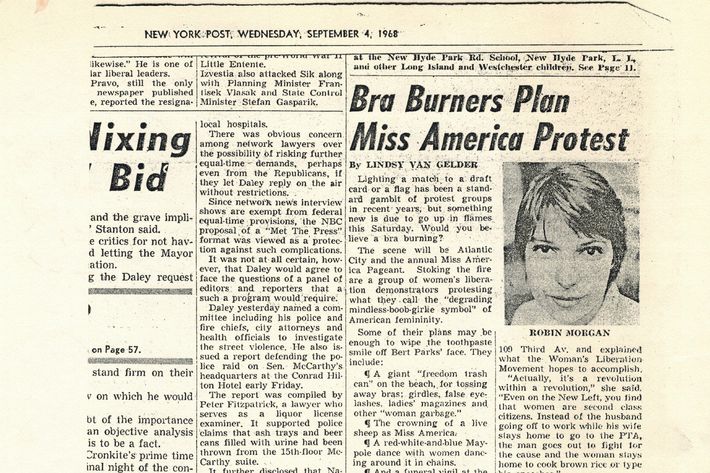

The Bra-Burning Heard Around the World

Consciousness-raising and study sessions were all very well, but some NYRW members craved action. In the summer of 1968, the group found something they all agreed was worth protesting: the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City. Women’s groups and activists from all over the East Coast (including civil-rights lawyer Flo Kennedy) converged to march, auction off a puppet in chains, and crown a live sheep Miss America. But it was a plan to set fire to feminine paraphernalia that drew New York newspapers. And then it was the protest banner dropped inside the pageant (which was broadcast live across the country) that attracted national attention after it aired.

Hanisch: I came up with the idea one night when somebody brought in this art film, Schmeerguntz. There were some clips in it of Miss America contestants walking along the ramp in their bathing suits being judged on their appearance. I thought: This is such a big deal in so many women’s lives.

Morgan: I hadn’t grown up watching Miss America because I’d had a weird childhood [as a child actor on the TV series Mama]. But I could understand the power it had over them, so I immediately leapt into the fray.

Lindsy Van Gelder: I’d been on tryout at the New York Post a few weeks when this press release from Robin Morgan comes across the city desk saying that they’re going to have this demonstration. I was sent out to meet Robin and the more she talked, the more my mind was going click, click, click. At the time, one story getting a lot of respect was guys burning their draft cards. New York Radical Women had planned to have what they called a “Freedom Trashcan” in Atlantic City, where they were going to throw in Playboy magazines and girdles and other articles of oppression. I’m a sucker for alliteration, so when I was trying to figure out a way to link this with respectable civil-rights protests, I came up with bra-burning.

Van Gelder: They actually never burned anything — the fire marshal didn’t want anything to ignite.

Morgan: We assembled in Union Square, where hundreds and hundreds of women suddenly showed up, so we got more buses. That was my first glimpse of holy crap! What are we doing here?

Bev Grant: We sang jingles that I wrote, like: “Ain’t she sweet, making profit off her meat.” I had never written a song before but it started my new career as a singer-songwriter.

Morgan: There were naysayers on the boardwalk yelling, You’re not pretty enough to get a man! But then there would be women who would come back and get a leaflet when their boyfriend wasn’t looking.

Shulman: I offered to pay for tickets for protesters to get inside. I had a joint checking account with my husband, and this was the first time I wrote a check without clearing it with him, ’cause he was the breadwinner.

Dobbins: When I was growing up my mother used to hold my head down in the sink and pour on this stinking [Toni home permanent] stuff to make my hair curl. So when we found out that Toni home permanent was the sponsor of the Miss America pageant we decided to sprinkle [permanent solution] along the aisles.

Grant: We carried little atomizers filled with Toni home permanent. It was kind of slapstick. Miriam took out her atomizer and she squirted me accidentally, so we got out of there in a hurry.

Dobbins: I got caught! I watched the end of the pageant in jail with women who were arrested for prostitution and I wrote on the wall of my little bunk, “Prostitutes of the world unite, we have nothing to lose but our pimps!” We talked a lot about how being a wife is a form of prostitution.

Hanisch: I was one of the four women that hung the “Women’s Liberation” banner from the balcony, which was scary but wonderful. I really hated interrupting the outgoing Miss America as she gave her farewell speech. We didn’t really mean to be criticizing the individuals — it was the whole idea of beauty pageants that we were criticizing.

Ellen Willis (then a counterculture journalist, from a September 1968 journal entry, later printed as “Up From Radicalism” in US magazine): I read about the women’s liberation protest against the Miss America contest. I’m dubious — won’t people think they’re just ugly, jealous women? But I remember what it’s like to be examined and compared at a party. And I’m proud that women are in the papers for fighting.

Morgan: The pageant has been called the birth of the women’s movement which is a) totally untrue, and b) deeply satisfying. NOW was already toiling away, so it’s not fair. But this protest caught the public imagination. The next week [NYRW] had our meeting and 300 women showed up! People were forming groups all across the country and it was out of hand.

‘Radical’ Goes Mainstream

NYRW had been regularly meeting at the offices of civil-rights organization Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF) where Carol Hanisch worked. But in the aftermath of the Miss America protest, so many new women appeared that the SCEF meetings grew cramped and chaotic. Among those new faces were counterculture journalists Susan Brownmiller and Ellen Willis.

Willis (from a November 1968 journal entry in US magazine): [T]he movement is growing so fast … Already I feel like a veteran. New women keep coming in, women who are just discovering their oppression, asserting for the first time their independence from husbands and lovers, overwhelmed that here they are listened to, respected … I’m starting to … realize other women are not the enemy.

Susan Brownmiller: After the Miss America protest, my friend said, “Did you know there’s this group talking about women?” Kathie was chairing my first meeting and she had some of her favorite consciousness-raising questions like, when you have a baby, do you want a boy or a girl? Peggy Dobbins said, “Kathie, you know that I had a baby and I had to give him away because I couldn’t find an abortion doctor.” That just blew things apart. People started to go around the room talking about their experiences. It came around to me and in my competitiveness, I said, “I’ve had three abortions, the last one was six months ago in Puerto Rico.” I thought I was in control but instead the tears welled up in my eyes because I had never said this out loud before.

Willis (from December 1968 journal entry in US magazine): There can be no sexual revolution in a vacuum … The “liberated woman,” like the “free world,” is a fiction that obscures real power relations and defuses revolution. How can women, subordinate in every other sphere, be free and equal in bed? Men want us to be a little free — it’s more exciting that way.

Allen: Some of the struggles in the early period really were around the tension of: Who’s going to be the leadership? We were so anti-leader from having been in situations where the men dominated that it was very hard to figure out.

Morgan: Certain women, and I was definitely one of them, would dominate the talking. So we tried to correct this. Each of us would get, say, ten chips, and we would sit in a circle and every time you spoke you had to spend the chip. Some women immediately spent all of their chips and then had to shut up for the rest of the evening and other women hoarded chips and then let loose with a lecture at the end. We were trying to reevaluate everything.

Sarachild: Our meetings exploded. The debates got hard to handle and we were swamped by mail. We fell apart because we couldn’t handle our success.

Hanisch: By December, some people were clamoring to split the group because it was too big. There was a vote on whether New York Radical Women should be broken up into smaller groups. Somebody suggested that we draw group assignment numbers, which actually happened. But most women didn’t go to the group they were supposed to and other groups formed out of it.

Morgan: We split [into smaller groups] but it was considered that we were all part of New York Radical Women. There was Redstockings. Ti-Grace Atkinson suddenly manifested and formed The Feminists. And those of us who wanted to do more actions became W.I.T.C.H.

The Rise of W.I.T.C.H. and Redstockings

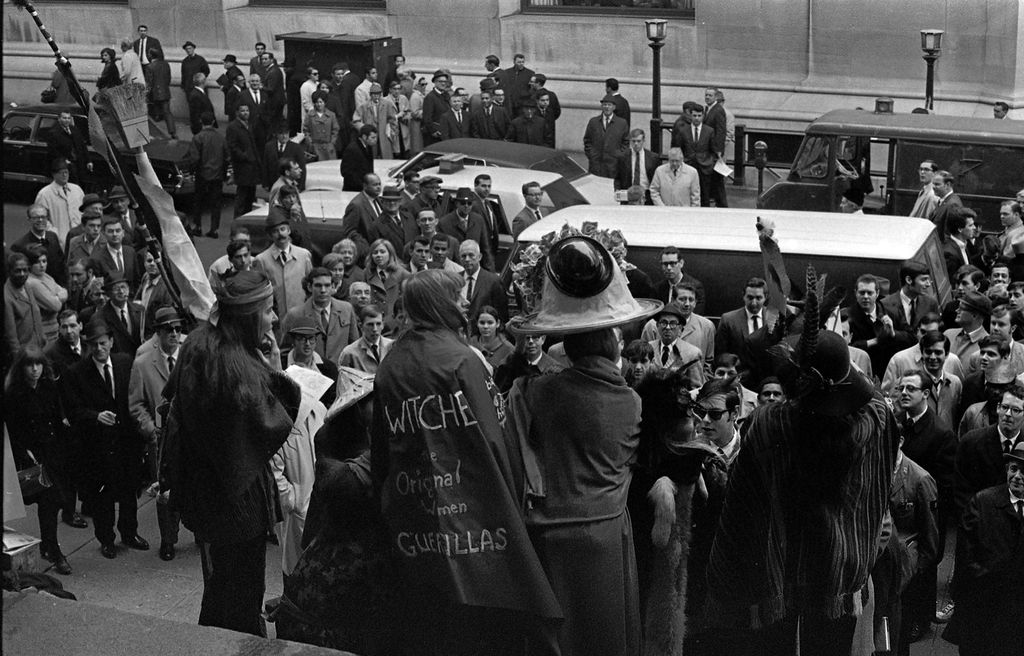

The membership of these splinter groups remained in flux, with women sometimes flitting between them. Founded by Shulamith Firestone and Ellen Willis and conceived as an intellectual study group, Redstockings included Anne Koedt, Irene Peslikis, Pat Mainardi, Rosalyn Baxandall, and Kathie Sarachild. They would establish their legacy with a fiery public abortion speak-out that inspired many women, including Gloria Steinem. The theatrical W.I.T.C.H. circle drew Peggy Dobbins, Judith Duffett, Bev Grant, Florika Remetier, Cynthia Funk, Robin Morgan, and Naomi Jaffe, who gathered to hex public targets like Wall Street.

Dobbins: I had to go to trial in Atlantic City after the pageant. On the ride back, I am sitting in the front seat, turned around, on my knees, and telling Florika Remetier and Marcia Patrick about all the ancient stuff I am reading about witches … and Marcia says, “Well, if women’s liberation does become a household word, there will be witch hunts and we will be the witches.” And I said, “Let’s embrace that!” That came from [civil-rights leader] H. Rap Brown saying: Embrace being called black.

Weston: Our first W.I.T.C.H. action was on Halloween, about six weeks after Miss America. I remember our chant: “Wall Street, Wall Street, mightiest wall of all street. Trick-or-treat, corporate elite, up against the Wall Street!” We made ourselves up in capes and feathers and things.

Morgan: We announced to the press that we were going to hex Wall Street at 9 a.m., or whatever. And then quietly two or three of us went at 4 a.m. and Krazy-Glued the doors of the Stock Exchange, so when we came back and pretended to hex it, they wouldn’t open. They had to take the damn doors off the hinges!

Weston: It wasn’t like Atlantic City where we saw nastiness on people’s faces and jeering; on Wall Street, you saw them a little bit afraid. That was a feeling of power.

Gloria Steinem (New York Magazine, April 7, 1969): A coven of 13 members of W.I.T.C.H. (The Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, celebrating witches and gypsies as the first women resistance fighters) demonstrates against that bastion of white male supremacy: Wall Street. The next day, the market falls five points. More witches and some black-veiled brides invade the Bridal Fair at Madison Square Garden. They carry signs (“Confront the Whore-makers,” “Here Comes the Bribe”), sing, shout, release white mice in the audience of would-be brides, and generally scare the living daylights out of exhibitors …

Morgan: Releasing mice at the bridal fair — that was really dumb. We went inside to release the mice and there were screaming women standing on chairs. And someone did a song with lyrics that said, “Here come the slaves / off to their graves.” That kind of turned off the women. The point was to try to say, we are here to support you — and don’t you know there is all this commercialization, and if you are really in love you don’t need 16 kinds of cups and plates?

Shulman: I was going to my W.I.T.C.H. meeting on East 3rd Street when I saw Kathie. She said, “Oh, don’t go there, you must come to Redstockings!” — they were meeting across the street. One was into having actions and one was into theory, but in fact, they were both doing consciousness-raising. My first Redstockings meeting was one of a series on sex. We talked about getting a man, not wanting a man; having no sex, having bad sex. I don’t think we talked much about lesbianism, though there were a number of us who were lesbians, or bi. I spoke about how I had a lover and I had a husband. Shulie said, when it came to her turn, “You have two men and I have none! It’s not fair!”

Brownmiller: Shulie was a ball of fire. At Redstockings’ abortion speak-out at the Washington Square Methodist Church in March 1969, she came out at the end and said, “We are going to see a day when technology is so strong that women don’t have to have babies from inside themselves.” These were very radical ideas.

Firestone (speech on abortion printed in Notes From the First Year): Those bodies belong to us. We don’t have to appear in your courts proving our mental incompetence to you before we can avoid forced childbearing! …. We will no longer submit to your definitions of what we should or should not be or do to become truly feminine in your eyes. For unless we have a part in creating the laws which govern our fate, then we will refuse to follow those dictates and laws.

From “Redstockings Manifesto” (July 1969): Our chief task at present is to develop female class consciousness through sharing experience and publicly exposing the sexist foundation of all our institutions. Consciousness-raising is not “therapy,” which implies the existence of individual solutions and falsely assumes that the male-female relationship is purely personal … The first requirement for raising class consciousness is honesty, in private and in public, with ourselves and other women.

‘The Last Hurrah’

By 1969, mainstream media and publishing had latched on to the women’s movement; Kate Millett, who had been an occasional presence at NYRW meetings, made the cover of Time magazine after her dissertation was transformed into the best-selling book Sexual Politics. Shulamith Firestone’s Dialectic of Sex soon followed, as did Sisterhood Is Powerful, an essay anthology edited by Robin Morgan. Some women in the movement headed back to Atlantic City again to protest the pageant that had alerted the world to NYRW and also hastened its demise.

Sarachild: The second Miss America protest in 1969 was the last hurrah of New York Radical Women. We really didn’t meet after that. But it was an important last hurrah because that was when the fist in the women’s symbol was launched.

Morgan: I designed buttons and had buttons made of that fist inside the women’s symbol. My then-husband drew it because I can’t draw, but I came up with the idea and directed the drawing. I have now seen it in refugee camps in the Gaza Strip, I have seen it in favelas in Brazil. Despite all my books and organizing, it is probably my biggest contribution to the women’s movement — and most people don’t even know I did it.

Brownmiller: There was a lot of personal anger from women who thought other women were suddenly rising to the top. Kate Millett suffered from those who resented her rise to fame courtesy of Time magazine. I think of her as one of the movement’s primary victims.

Weston: All of these things really did need to be discussed, like: When people start writing about women’s liberation, should the money go into a women’s liberation fund? But it wasn’t possible to hash things out in a minute way after Miss America because it all just took on a life of its own.

Morgan: I have been accused of stealing the phrase “sisterhood is powerful.” Shulie was tortured in Redstockings when she published anything. She had the strength of her own brilliance and madness — though at great cost. Years later, when she had become an Orthodox Jew and an astrologer, I reached out to her and she wanted nothing to do with feminism.

Allen: The limitations in the early Women’s Liberation Movement were that, for the most part, we were college-educated and primarily white. This was the period of [racial] separatism, when a lot of the black women that I knew weren’t interested in joining.

Grant: I get why black women wouldn’t join us — their experience was different. They were coming from a whole exploited and oppressed people, whereas we were coming from just trying to fight against the oppression of men. There are so many more layers of oppression for women of color.

Weston: I want young people to feel proud of us, which doesn’t mean we should sweep problems under the rug … but I want them to feel proud of a tradition, so they carry it on.

Morgan: For a long while when young women would ask, what do you have to teach us? I would say, only our mistakes. But we didn’t only make mistakes. We did lay down a trail as much as anybody can in a shifting society and a very violent time. There is a glorification of the ’60s and how great it was. But don’t envy us for having done it, do your own version of it.

Order Highbrow, Lowbrow, Brilliant, Despicable: 50 Years of New York, a celebratory book chronicling the magazine’s history with powerful images and behind-the-scenes stories from staff and subjects.