Olivier Zahm on Why Magazines Still Matter

Purple magazine was founded 25 years ago by a young French art journalist named Olivier Zahm and his then-girlfriend, Elein Fleiss. Back in 1992, modems were truculent novelties which screeched and hissed to let you know they were slowly linking you to this new thing called the World Wide Web, and lots of clever young people were starting their own magazines — which, at the time, felt like the most efficient way to embody a cutting-edge sensibility, make arguments, and change the larger culture. As Zahm told me, “The magazine was a voice of a generation. Of a context. I was struggling, as an art critic, and a journalist, to push this new generation, and my dream was always to do a magazine.”

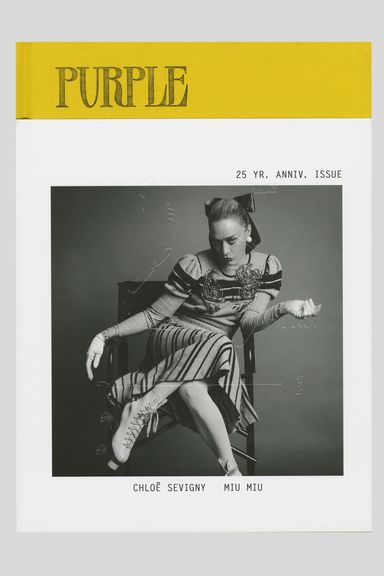

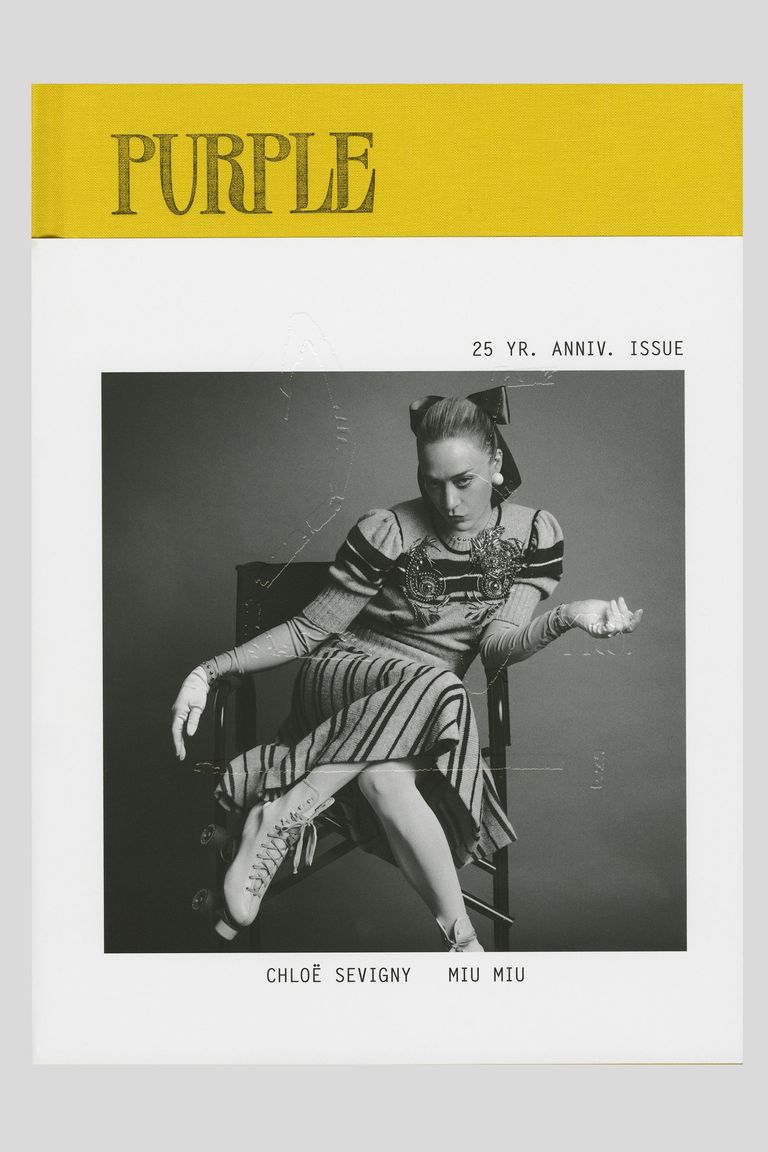

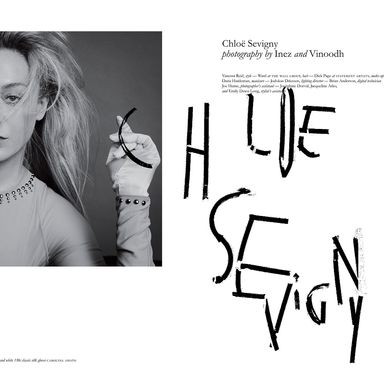

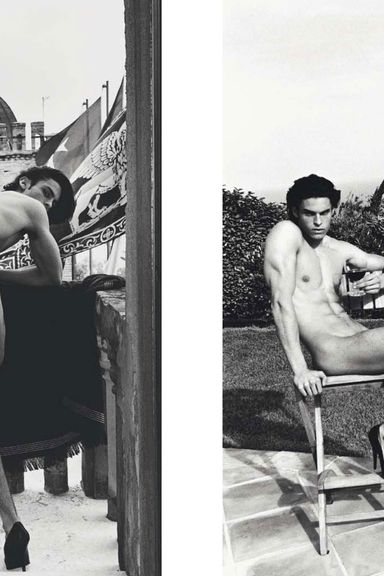

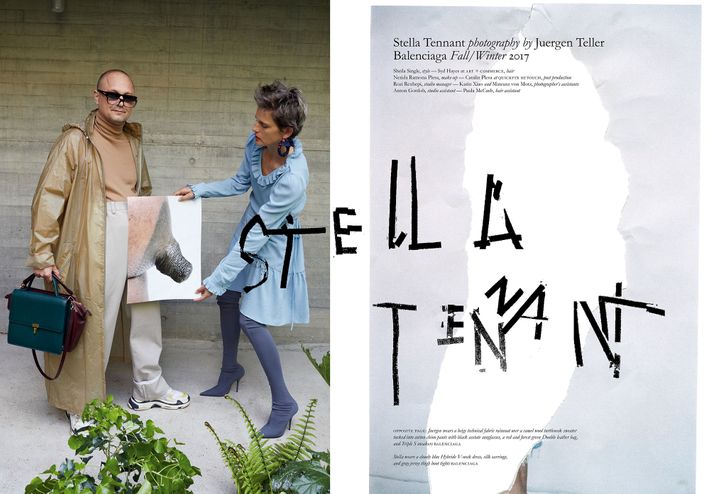

Ten years in, Fleiss left, and Zahm steered Purple toward becoming a fashion magazine, which looked to be a more promising business model. He hired photographers such as Juergen Teller, Terry Richardson, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Mario Sorrenti, who changed the way fashion was shot, draining it of glamorous artifice in favor of a frank, deadpan sexuality. Purple is a fashion magazine in which (it must be said) many of the models, male and female, often looked a bit like they just had sex, or might soon be having sex. Zahm also took up the camera himself, and does many of the interviews, too, covering his friends from the art and fashion worlds. In 2013, Chloë Sevigny told the Cut that she’d been in “almost every issue” since they met, adding that, “He makes you feel warm and is flattering and showers you with adoration. And he has very good taste.” (She’s in the current anniversary issue, photographed by Inez and Vinoodh.)

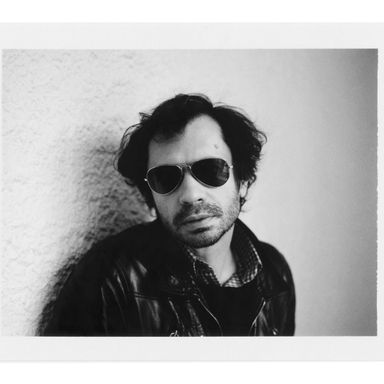

Plenty has changed in the last 25 years. Lately, Zahm is more and more in Los Angeles, where his girlfriend, Amanda Wall, a former model and creative director for a beauty brand, lives. He is active on Instagram (@ozpurple, which is full of pretty girls and unsmiling selfies, has 112,000 followers). At 54, his generation’s cutting-edge is now the establishment, and Purple, the luxury periodical with art-world cred, is just one of the activities of his Purple Institute — which is where he makes money consulting for brands. And while cultural attitudes around sex, power, and exploitation have evolved dramatically, Zahm has stuck by his brand of louche sexual liberation, not to mention his bed-head, tight jeans, motorcycle jackets, and (prescription) Ray-Ban aviators. Dial up Purple.fr, and, in addition to sections for “travel” and “art,” there’s a section called “sex” (naked young women, artily posed). Oh, and one of the main articles on “art” is a piece headlined: DO YOU HAVE 15 MINS TO SEE NAKED GIRL MARIA FORQUÉ TALK ABOUT INSTAGRAM AND CENSORSHIP? Plus ca change, where Purple and Zahm are concerned.

We spoke this month at the Neuehouse co-working clubhouse, where, to save money, Purple now has their New York offices.

Neuehouse is so strange. It feels like the world’s swankiest university student commons. Didn’t you have proper offices in New York?

I had a loft next to Grace Church on 12th and Broadway. I loved it; there were no elevators for the fourth floor.

Did you live there also when you were in town?

No, I was not supposed to live there. They had those rules, but they don’t always enforce them really. [Laughs.] That’s the old New York. I’m surprised it was even like that recently. The old New York would have those loft spaces, but now everything is so merchandised. When they doubled the rent to $15,000 a month, we left.

And you’re in New York less, and Los Angeles more. Why’s that?

It’s a combination of things. The city became more interesting. There are more people there.

There’s definitely more vitality out there in L.A. than there used to be, especially in art world and the art scene, which is a lot of what I write about. I know younger artists are moving there and just can’t take this place. If you move far enough out in Bushwick you might as well move to L.A. [Laughs.]

A little magazine is a small boat floating, and there’s a stream pushing you. I’m going there. I’m not resisting the stream. And I’m 50. I’m over 50, and L.A. is relaxing. New York’s fantastic. I need the energy of New York. I wouldn’t have done the magazine without New York. New York gave me and still gives me a lot of energy.

When did you first start coming here?

It was actually in ’87 with my girlfriend. We decided to have a summer trip. I was a young art critic, so for me, it was really exciting to see the Sonnabend Gallery …

And you met people …

So there was little, tiny, tiny circle that I knew, or people told me to meet. And I immediately enjoyed and understood that contemporary art was totally part of everyday culture in America. That it wasn’t just an extension of art history, it was art today. You know? In Paris, we always need historical legitimization. If you don’t know every artwork of Marcel Duchamp you can’t be an art critic. There’s a feeling of a sense of freedom that New York gives you because you can create a fiction in New York. You can recreate yourself, and also there’s positivity and excitement for what’s new.

So you kept coming back.

Yes. And at the time I could survive by just writing a few articles, art catalogues, and I don’t even know how I did but it was very little money.

Where did you stay back then, when you came back to New York?It was always, always, at friends. Or an artist studio on a couch literally was all — it was always with friends. We used to share apartments and I used to let people stay in my apartment in Paris. There was a good system. Airbnb before Airbnb. [Laughs] I stayed at John Currin’s studio, it was on, on Delancey, and John was a friend. I was literally sleeping in the studio smelling the terrible smell of the paint all night long and then during the day on my clothes. And as soon as I could get an apartment I got an apartment in Brooklyn in Williamsburg for $300, next to the bridge. And then I curated a show at PS1 in 1996. I stayed almost one year, in this apartment in Williamsburg. And I fell in love with a girl there. I thought about moving the magazine here, but Elein Fleiss was always telling me, ’Olivier, our responsibility is to do an interesting magazine in Paris. New York has enough magazines — ’

Why was it called Purple?

I did this magazine called Blue with a friend, Nicolas Bourriaud — he’s a good art critic. He did Relational Aesthetics — I was part of it. I like the idea of a color for an art magazine and then I asked a few friends, artists, what kind of color. And Dike Blair, he’s an American artist, told me about this “purple prose” concept. He said, purple is interesting because purple prose means something, it’s like pulp fiction. The color purple, we don’t have it — it’s American, it’s English, and it sounds great and it’s also weird. It’s such a weird color.

It also sounds great in a French accent.

Really? [Laughs] It’s also very sexual and a bit, slight porn in a way … This like, over, over-sensual. Also, you had Purple Rain. Purple was like, romantic.

Originally it was called Purple Prose …

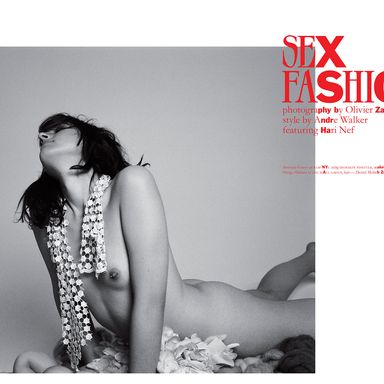

Yes, and then we used purple as just a way to do different magazines, like Purple Fashion, Purple Sex, Purple Fiction. Now I do one blog, mixing everything.

Why did you turn it away from being an art magazine? Was it watching your friends become more successful, the establishment in fashion?

Exactly! I was, in a way I was left on the side, because they made more money, they were more successful than me as an editor … so, I said okay. I said to myself, ‘now enough of this. They’re all successful. Now if I continue in the business of magazines let’s do a successful fashion magazine.’ That was my agenda. I didn’t want to do an alternative magazine anymore.

Purple has always been sexually frank. There is a lot of nudity, and, notably in your blog, a celebration of sex and beautiful women. It’s been called sexist. So have you. Do you ever think you have gone too far?

I understand Purple can be perceived as a very sexualized fashion magazine, as I believe that nudity is part of art and fashion vocabulary, and history, and I am not afraid of it, as long is clearly not pornographic. Many times I had to cancel stories that I felt went too far in the sexual objectification of women, and were against the Purple ethic.

How would you describe that ethic?

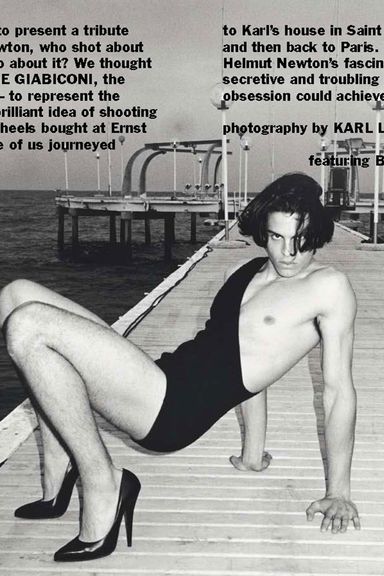

The belief that the male sex could be superior to any gender and should dominate areas of political and social life, as well as cultural production, is an unacceptable discrimination that I have always fought in Purple, since the beginning of the magazine. And I will continue to fight sexism in my magazine. I started it with my girlfriend Elein Fleiss, and always worked with women in the magazine, and encouraged the conscious editorial politics of having women artists and women photographers in its pages. In addition, it’s important to deconstruct the traditional stereotypes of gender roles, and also express various sexual orientations and their specific aesthetic in fashion which give Purple a very large spectrum of images! We did recently a whole issue on gender fluidity in fashion for example. And when it comes to nudity I tried also to have male nudity as well. Japanese customs has blocked Purple many times, as penises are even more censored than women’s pubic hair.

In the introduction to the anniversary issue, you write: “It’s been years now that younger generations don’t use magazines to express themselves … Social media now generally satisfy the need for images, contacts and creativity.” So what’s a magazine for?

It’s not about the information anymore. There’s enough information immediately accessible on your phone. You don’t need a magazine to be informed. More than that, you’re under-informed with a magazine compared to what you get on the internet every day, even myself. It’s a source for my magazine. Maybe the main source, so what’s left for printed publications?

The problem of the internet is that it’s shaped the same way for everyone. As a printed publication we design the information. We curate it and we design it on paper, and this makes a big difference. This is why we create the story. I think that magazines are very important because … not only mine, but if we disappear, the public will lose a point of reference. You will be lost into your own interests, basically. And that’s very important because in this massive stream of everyday information, what’s left at the end of the day? Nothing.

That’s why all the big Hollywood publicists always try to get the stories about their star client appear in print.

You don’t need to put me in print. I’m okay to be on the internet.