“Oh, Fuck You Bill,” I remember telling the TV when I watched President William J. Clinton wag his long, bent finger at the camera and declare, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky.” It was January, 1998. I was 21, a senior in art school, alone in my studio talking out loud to the TV in disbelief — not at the fact that the president was being called to answer for something gross, but that his certitude was a dead giveaway for his impropriety. Something in my gut told me he was lying. The way he distanced himself from her by saying THAT WOMAN, as only a man could do to a woman he’s slept with, was a tell. There was anger in his voice, at being called out — like a boy in high school caught messing around with an unpopular girl might say, “Ew, her? No she’s gross.” I was used to men lying. I’d watched the Anita Hill case, the O.J. case, Trump’s violent assault on Ivana, his first wife. When had a man ever actually admitted to any wrongdoing? Clinton himself had already been accused of so many things that it could hardly come as a surprise to anybody that it was happening again.

It wasn’t just that I was close in age to Monica Lewinsky (she was 22 at the time of the affair) that made me sympathetic to her. I didn’t have much in common with Monica at all, except that I knew what it was like to be an intern surrounded by powerful men who made sexual overtures. I could imagine how seductive the situation must have seemed to her. How alone she must have felt. It made sense to me that she had flashed the president her thong, or kept the dress he came on. Her actions were so youthful, irrational, and relatable. And though I never found Bill Clinton attractive, I’d listened to plenty of liberal women describe elaborate sexual fantasies they had about him. He was one of those guys. Powerful. In his prime. The kind of man that might be irresistible if he trained his gaze on you.

Watching him deny his actions, deny her side of things essentially, felt too familiar. I knew what it was like to have confided in someone and have them blow your trust. She’d gone and seduced the leader of the free world. Or he’d seduced her. Or whatever. It didn’t matter to me. The power imbalance felt palpable and absolved her of guilt in my opinion. All I could think about was that Lewinsky’s dumb affair with Bill Clinton was going to ruin her life. She would become the most reviled woman in the Western Hemisphere, by liberals and conservatives alike. It wasn’t right.

As he made his statements, Hillary stood next to him in a yellow skirt suit. I was disgusted, disappointed, and wanted her to run away screaming, not stand by him. Her behavior didn’t square with anything I’d ever been taught about feminism. I figured that surely, after this press conference, she would leave. But the next day she went on the Today show and blamed the whole thing on a “vast right-wing conspiracy” against her husband. Which, to be fair, there might have been, but it seemed like a convenient dodge and left a very bad taste in my mouth. “Seriously?” I remember thinking. I was starting to get more and more angry. Though I liked the Clintons and had grown up with them — my parents had voted for them and I’d even helped campaign for them — I wasn’t swayed by the calls of partisan politics at the time. I was able to see this for what it was: utter bullshit.

In the weeks that followed, the Lewinsky scandal clouded every conversation I had. At the time every person I knew was staunchly liberal. I couldn’t believe the things they were saying about the situation — even Gloria Steinem came out to defend him in the New York Times! No one seemed to care or even agree with me that Bill was a scumbag, but that didn’t stop me from provoking endless, circular conversations about it. I wasn’t interested in whether it was worth impeaching him. I just wanted to find someone who sympathized with Monica. I was accused of being a secret conservative by a teacher. One (male) classmate implied I was being priggish — invoking “the French” approach to politics, meaning one in which we shouldn’t interrogate the sex lives of politicians because that was some kind of lame, puritanical, American moralizing. My friends would change the subject when I brought it up. My boyfriend at the time indulged my fervid rage over the subject, but was more interested in debunking the conservative reactions. I became irascible on the topic, testing the waters with every woman I knew, to see if I could find one who would see it as I did. I couldn’t.

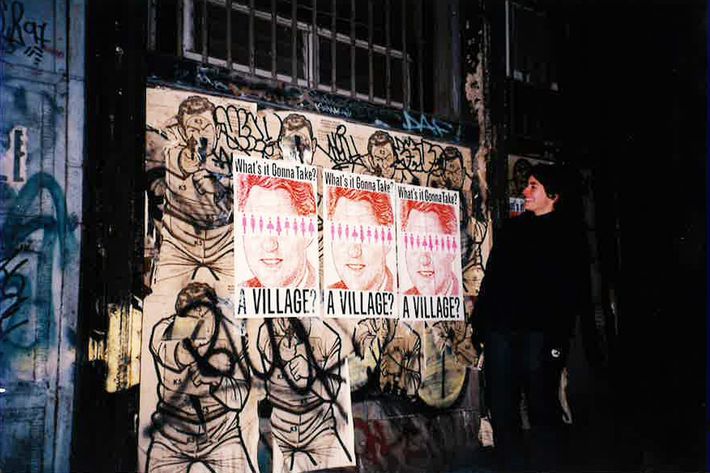

I wouldn’t drop it. I felt a little crazy, even isolated. And so I decided to focus my senior thesis on Monica’s plight. In my silk-screening class I made a poster with a drawing of Bill Clinton’s face. Across his eyes I placed a bar of female-shaped bathroom symbols and in big wood type the words: What’s It Gonna Take? A Village? The message seems hackneyed to me now, but invoking Hillary Clinton’s famous 1996 book, It Takes a Village, expressed my frustration with them both. I decided to plaster my posters all over Soho as a tiny scream into the void.

It Takes a Village (to raise a child) was predicated on the idea that the welfare of an individual depended on the efforts of the whole community. By the time the Lewinsky scandal broke, Bill Clinton had been accused of sexual harassment by Paula Jones, and was accused of an extramarital affair by Gennifer Flowers. In addition to that, he’d allegedly used Arkansas state troopers to cover up numerous affairs. I believed the women, and felt it was the height of hypocrisy for Hillary Clinton (and many woman I knew) to discount these stories. Using Hillary’s slogan and his face summed it up for me. What I was really asking, though I didn’t know it then, was: WHAT IS IT GOING TO TAKE TO BRING DOWN THE PATRIARCHY. More than a village, it turned out.

There have been some interesting essays this week about the reckoning we, as liberals, need to do about the Clintons. Even today, just thinking about how it felt to be on “the right side of history” makes me mad all over again. And it gives me a little comfort that I was right. Eventually, I had to let it go. Bill stayed president. Monica moved to New York. We got saddled with the Bush years and terrorism made blow jobs in the White House seem like small potatoes. But here we are again. And if we don’t deal with it now, we risk being on the wrong side of everything forever.