A man raises his arms skyward in anguish, his face contorting with anger. He’s just discovered that his beloved fiancée has been spreading rumors about him, and he’s screaming his heart out. “You are tearing me apart, Lisa!” he howls.

It’s hilarious.

This is perhaps the most famous scene in one of the most famous bad movies of all time: The Room, a 2003 independent film that was, by all accounts, an achingly heartfelt passion project for director/star/producer/writer Tommy Wiseau, one that reportedly cost him $6 million to make. In it, Wiseau plays Johnny, a good-natured guy who’s got it all — a beautiful wife-to-be, whom he showers with gifts and with whom he enjoys a passionate (and uncomfortably graphic) sex life. He’s got a best friend, the rakishly handsome and loyal Mark who, as it happens, is also sleeping with said wife-to-be. He’s a mentor to an orphaned neighbor named Denny, who may or may not have a drug addiction and appears to be anywhere between 16 and 35 years old. It all comes crashing down, as these things do, though the how and why is so disjointed that it defies description.

The Room is not a comedy of errors; it is almost purely errors. I’ve seen it three times in the theater, and have watched countless clips on YouTube — at this point, going back to find new fuck-ups in the plotting, framing, acting, writing, and cinematography has become something of a hobby of mine. There will never be a day I don’t delight in trying to figure out, for example, why Wiseau decided Lisa’s cocktail of choice should be “scotchka.”

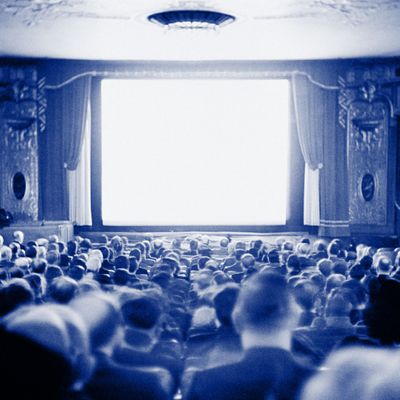

And I’m not alone in my fascination, either. In the nearly 15 years since its release, The Room has become a cult classic, one with its own set of joyful rituals that are now routinely reenacted by theaters full of fans. When the mysterious framed pictures of spoons that decorate Johnny’s apartment are in frame, we toss plastic spoons at the screen. When a character you’ve never seen before enters, we collectively demand to know, “Who the fuck are you?” When Johnny tosses a football in an alley with his friends, we do the same in the theater aisles.

Indie cinemas around North America still regularly show the movie, and there are even some in Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, and elsewhere that play it monthly. It inspired a book, The Disaster Artist, about its making, written by Greg Sestero, the actor who played Mark and the closest thing this world has to a Wiseau confidante. That book, in turn, has been adapted into a film, out next month, in which Wiseau is played by James Franco (who also directs). Thousands of subpar movies have been released since The Room, most of which have faded into obscurity, and yet Wiseau’s opus lives on. All of which leads to a question each and every person who has seen, and has loved, The Room has had to grapple with: Why on earth am I watching this garbage?

When it comes to dissecting bad movies, there’s perhaps no greater expert than comedian and actor Paul Scheer. On the popular podcast How Did This Get Made?, which Scheer co-hosts alongside fellow comic actors Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael (who is married to Scheer), the trio invites guests to help them pick apart awful films that span from low-budget curios with names like Ninja Terminator to bonkers big-budget bombs such as Spider-Man 3. (All three co-hosts have roles in The Disaster Artist.)

To Scheer, it’s important to define the terms. Not all bad movies are entertaining. To be worthwhile, they require a sense that someone was actually trying. “There’s the type of movie we don’t really like, which is being bad for bad’s sake, because then I feel that’s cheating,” he says. “I feel like that’s ‘I don’t care.’ When you look at Birdemic or The Room, they care! They just missed the mark.”

Making a purposefully lousy movie is like wearing a Female Body Inspector T-shirt: You might get a cheap laugh, but ultimately, you’re just a guy with questionable taste. The initial Sharknado was cheesy insanity, but by the time the fourth in the series was released, the formula had been worn out. There was nowhere left to go — what started as cheeky self-awareness and homages to the B-movie genre faded into lazy self-reference. Bad movies are great because there are layers, even if they are unintentional. Take that away, and you’re left with a desperate class clown, calling the teacher names for cheap shock value.

Scheer has his theories developed from his years of immersion in the best of bad cinema, but there has been very little academic study to directly question why people love terrible movies, save for one paper published in 2016 in the journal Poetics. In it, Keyvan Sarkhosh, a German postdoctoral student at the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, writes that the people he surveyed who claimed to be fans of “trash cinema” had higher levels of education than the average population; they also reported that they tended to frequent museums and art-house theaters.

I sorely wish this meant The Room fans were geniuses, but, alas, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. But if consumers of bad movies are also fans of highbrow art, it could be because the appeal of both comes from the same place: Analyzing the pieces with others to find out what the creator was trying to say is still doable when the creator is talentless. It just so happens that the mistakes in Troll 2 also lend themselves to inside jokes; if you get why “You can’t piss on hospitality” is funny, you get to feel like you’re part of the club.

And yet there is a nagging sense that this is a mean-spirited exercise, punching down at a hapless auteur who isn’t around to defend himself. But I think the pleasure isn’t wholly derived from the misfortune of the filmmakers; rather, it’s that sense of belonging — of being among those in on the joke — that’s the main draw. Watching The Room has become a social experience: Consider again the aforementioned tossing of plastic spoons and/or footballs. You get the feeling that you are sitting among your people, and there’s exhilaration in knowing that everyone around you speaks your language. The last time I took in a screening, one of the organizers recognized me in line. His greeting of “So, how’s your sex life?” would have had me searching for security in any other context. Here, it just got a grin and an “Oh hi, Mark.”

“Part of the idea is that the presence of other people can intensify the emotional experience,” says Mina Cikara, an assistant psychology professor at Harvard who has authored studies on how humans experience schadenfreude. “To the extent schadenfreude is still pleasure, despite the fact it’s malicious, one possibility is it amplifies that pleasure by co-experiencing it with other people. Another part of it is it’s affirming of your viewpoint. If I hate a thing and you hate a thing, then I know you see the world the same that I do. That can be a very satisfying experience.”

Likewise, Scheer compares his podcast to talking about a movie with your friends in the car ride home, once a small communal experience with a few friends that has now extended to exchanges with strangers, subreddits, and Twitter. As Sarkhosh explains, “the idea of being part of a community which is somehow on the margins of the mainstream and offers audiences the possibility to dive deeper into the things they love” is a big part of the enjoyment.

It’s not a coincidence, then, that episodes of How Did This Get Made? — which were initially taped in a recording studio — are now primarily recorded in front of live audiences. Among the most powerful charms of shit cinema is the sense of community that comes along with it. “I think part of the fun of the live shows is seeing the energy that our audience brings to it with their notepads and they’ve made their signs,” says Scheer. “I think that’s one of the reasons the show has had the success it’s had … It’s more fun when you can all feel like you’re sharing in this pain together.”