Large swathes of my childhood were spent inside a gym, what I remember as a giant concrete box, fuzzy blue-floored and smelling like chalk and warm bare feet. My teammates and I spent hours conditioning; we did five sets of 25 push-ups, crunches, laps around the floor. We jump-roped and took ballet classes to learn how to hold our hands with more grace. On the weekends, we put on long-sleeve leotards and swishy black track pants, rode in the back rows of minivans to strange gyms, and competed, climbing up on podiums when we won. I loved it, until I didn’t.

The change was gradual, I think. Probably I maxed out on natural ability, and learning new skills became more scary than not. My stomach started hurting. My ankle seemed, always, maybe a little sprained. I started second-guessing distances and launched without enough conviction down the runway, off the springboard, and sometimes smack into the vault.

My coach saw right through me: You’re not injured, he said. You’re just scared.

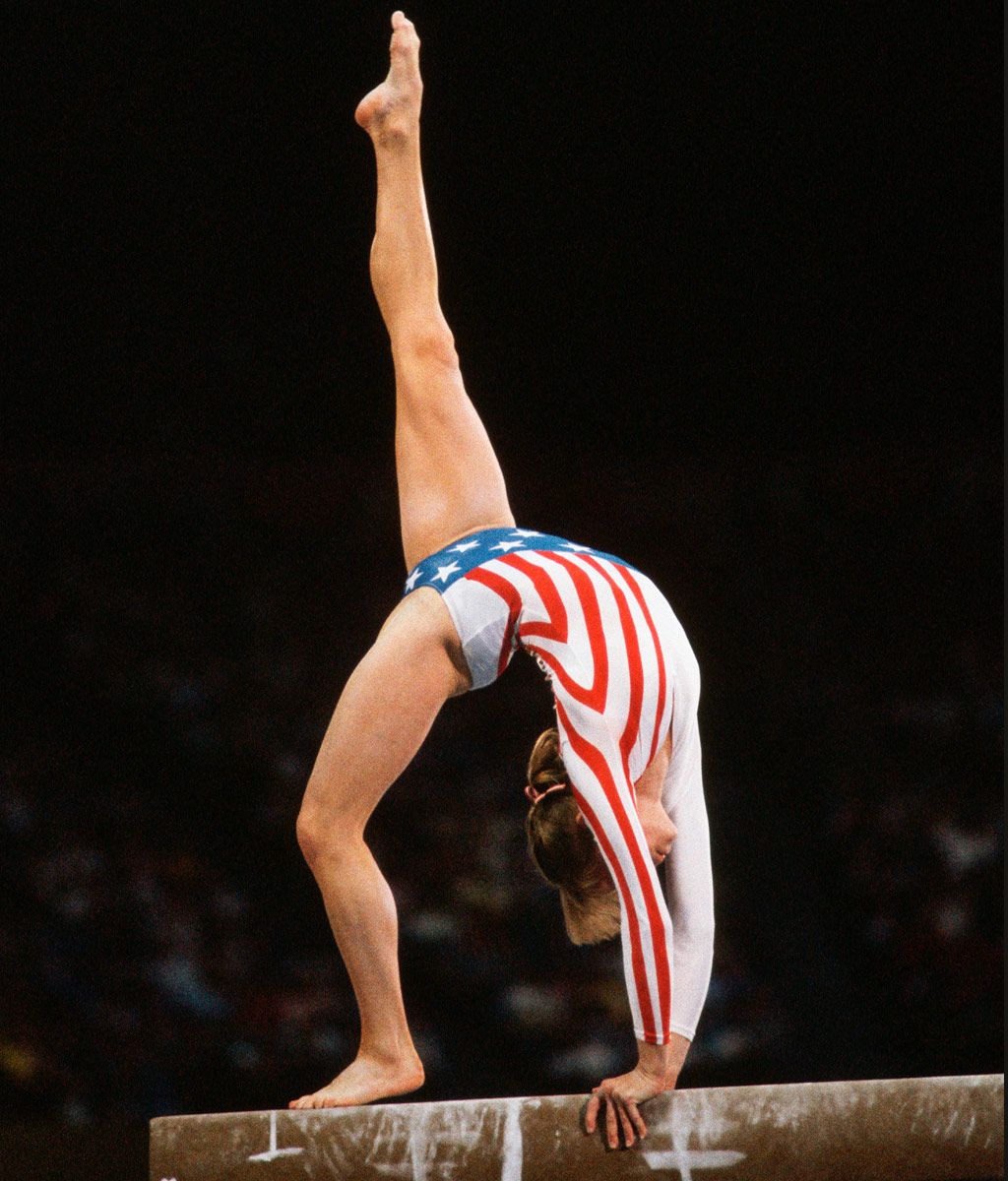

This was more than 20 years ago, the summer of the 1996 Olympics, the summer of the Magnificent Seven. Even people who aren’t fans of gymnastics probably know some of their names — like Shannon Miller, Dominiques Dawes and Moceanu, Kerri Strug — and the lengths they went to in order to become the first-ever Americans to win a gold medal in the team competition for women’s gymnastics. The category was and is called “women’s,” despite the fact that international-level gymnasts are often girls. The youngest member of the Magnificent Seven was 14. The oldest were 19.

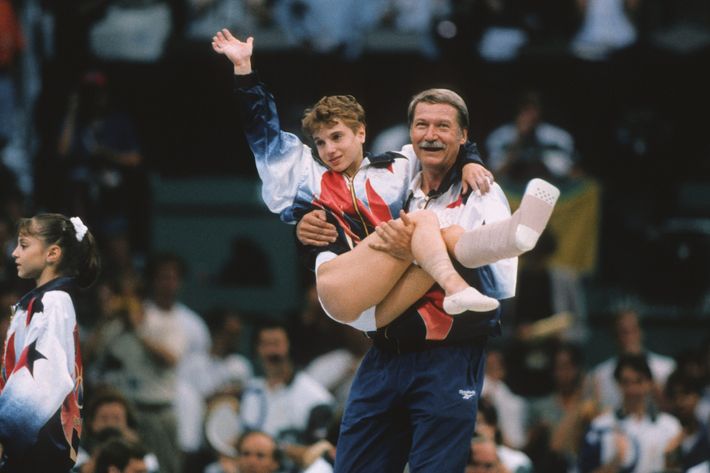

Kerri Strug, petite with a perky flop of short hair, was one of the 19-year-olds. In the final event for the team competition, Strug fell after her first vault and limped noticeably. As she prepared to vault again, coach Bela Karolyi roared: “You can do it. Kerri, you can do it!” The gymnast took deep, visible breaths. She ran and hurled herself up and over the vault. She landed on two feet, then hopped very quickly to one, making sure to salute the judges before collapsing to her knees.

“Kerri Strug is hurt! She is hurt badly!” the announcer cried, failing to keep the grim excitement from his voice. “Probably the last thing she should have done was vault again, but she did!” At home, we watched with the same incredulity. It was grotesque and thrilling, and if you were a young gymnast, you watched what Kerri Strug did and wondered whether you were capable of doing it too.

Marta Karolyi, wife of Bela, was one of the people who helped carry Strug away from the vault. At the medal ceremony, it was Bela Karolyi who carried Strug, her leg in a giant cast, to the podium, where she stood with a severely sprained ankle, two torn ligaments, and a gold medal.

This moment in Olympic history is celebrated and cherished, recognized as a supreme feat of strength and commitment to winning at any cost. In the lead-up to the 2012 Olympics, Team USA produced a segment on Strug’s “Gold Medal Moment,” in which the gymnast, her coach, and admirers glowingly recount the legendary vault. It has over a million views.

Twenty years after that moment, much has changed about gymnastics and gymnasts. For starters, they’re slightly older: In 1997, the minimum age for a gymnast’s participation in senior-level events like the Olympic Games was raised to 16. And they win more: Since the first team gold medal in 1996, Team USA has won two more, in 2012 and 2016.

Today’s gymnasts flip more, twist more, and fly higher, inviting more physical risk than ever before. And they no longer look as though you could snap them in half. Today’s gymnasts, though still short in height, look as though they could conceivably snap you in half — they ripple with muscles, their thighs are solid, their biceps bulge beneath leotards in ultrafemme pinks and purples. This combination, to me, is exciting: Contemporary gymnasts are a modern breed of feminine, one that borrows from traditionally masculine traits like strength and power without sacrificing elements of stereotypical femininity, like ponytails and crying, grace and discipline.

It is with these qualities — grace, power, and yes, sometimes still the jaunty ponytails — that over 265 people have accused Larry Nassar, the national gymnastics team doctor for more than two decades, of sexual abuse. Some are famous, like Olympians Aly Raisman, McKayla Maroney, Simone Biles, Gabby Douglas, and Jordyn Wieber. Others are less so, like Jamie Dantzscher, Jeanette Antolin, and Jessica Howard, who spoke about Nassar’s abuse on an episode of 60 Minutes that aired in February of 2017, following an explosive 2016 exposé by the Indianapolis Star alleging a pattern of abuse in the sport. Nassar’s connection to American gymnastics is a deep one: In a photo of Kerri Strug limping after her injury at the 1996 Olympics, there he is, arm outstretched toward the young gymnast. The first report of his abuse occurred the following year, in 1997.

Twenty years later, in November of 2017, Nassar pleaded guilty to seven counts of first-degree criminal sexual conduct. The next month, he received a 60-year prison sentence for child pornography. Over 150 women and girls made statements at Nassar’s sexual-conduct sentencing hearing last month, with about 60 more at a different hearing this week.

This past fall, Aly Raisman also spoke about Larry Nassar on 60 Minutes. “You don’t want to let yourself believe,” she said, “I am a victim of sexual abuse.” Raisman explained many have asked her why Nassar’s victims didn’t speak up sooner; this question, she asserted, is misplaced: “Why not look at — what about the culture? What did USA Gymnastics do, and Larry Nassar do, to manipulate these girls so much that they are so afraid to speak up?”

USA Gymnastics has reacted to the Nassar scandal, though most feel the organization’s actions are much too little, much too late, and have been primarily aimed at saving face. Of the most damning: According to a report from The Wall Street Journal, in December 2016, USA Gymnastics paid Olympian McKayla Maroney $1.25 million in exchange for her silence about the years of abuse she suffered at the hands of Nassar. As the scandal has built in intensity, top USA Gymnastics officials, including its president and all members of its board of directors, have resigned.

As an organization, USA Gymnastics seems hugely at fault for failing to protect gymnasts from Nassar. But as for forming the culture of gymnastics, two individual names come to mind: Bela and Marta Karolyi, celebrated coaches who’ve been prominent in the sport for decades. While many of the last 30 years’ star gymnasts have had individual coaches, nearly all of them spent time training at the Karolyis’ Texas ranch.

Being invited to the ranch was a privilege; it meant you were chosen, that the all-knowing couple recognized your skill or your potential. In operation since the 1980s, Karolyi Ranch has been part of the Olympic team-selection process since 1999. Rumors have swirled about the intense atmosphere, about strict diets, bodily scrutiny, and harsh coaching tactics. In her 2012 memoir, Dominique Moceanu — 14 when she was coached by the Karolyis at the 1996 Olympics — described training for hours without air-conditioning or food. No parents were allowed on the ranch, where cell-phone service is said to be spotty, and Larry Nassar was reportedly permitted to treat gymnasts unsupervised, in their ranch dorm rooms.

Last month, Simone Biles tweeted she was abused by Larry Nassar, indicating the abuse occurred at the ranch. (The Karolyis have denied knowing anything about Nassar’s abuse prior to his dismissal from USA Gymnastics in 2015.) Three days later, USA Gymnastics announced that Karolyi Ranch — which is currently being investigated by the state of Texas for alleged sexual abuse — would no longer host training camps, canceling one that had been scheduled for the following week.

In Larry Nassar’s wake, the Karolyis’ names are often invoked as the instigators of the toxic culture Raisman and others have railed against: A Washington Post article about the kinds of coaching tactics that enabled Nassar’s abuse, for example, declares, “When Bela and Martha Karolyi defected to the United States from Romania in 1981, they brought with them Eastern Bloc training techniques designed to push children to their physical and mental limits.” The implication seems to be that these outsiders came equipped with methods that may have been effective in winning gold medals but that we now see are too harsh and severe, methods that led us here, to a place where a predator’s abuse was allowed to fester and proliferate among young athletes. If there’s anyone else to blame besides Nassar, we seem to be saying, it’s these guys, with their accents and their foreign-sounding names and their intensity.

But what many have overlooked is how American the Karolyis are, and have striven to be. The Karolyis are the definition of self-made, defectors who fled with nothing and rebuilt their international reputation on American soil. Their facility, after all, is an actual ranch, home to gymnastics facilities and dorms, yes, but also a bizarre mix of camels, horses, peacocks, goats, and deer. Bela Karolyi has been filmed joyously driving over the ranch’s 2,000 acres on an ATV, feeding his livestock while sporting a cowboy hat. On camera, his coaching was the opposite of stoic — loud and warm, shouting encouragement and crushing his tiny gymnasts with hugs after a performance. His visible glee at a difficult job well-done seems very American indeed.

In America, we lack social support systems; what we have instead is a system that depends on individual wealth and ability. People who deserve them, our system would have you believe, get better doctors, because people who work hard at the expense of themselves achieve more. Several of the gymnasts, including Raisman, have explained that they were told Larry Nassar was “the best” and they were lucky to be treated by him. These gymnasts strove to reach the top of their sport, and some of them did, becoming the best in the world. They achieved, and — in a cruelly American trick — what they got was Larry Nassar.

In her 60 Minutes interview, Raisman discussed her reasons for speaking out: Emphasizing the need for sweeping change within the sport, the gymnast invoked the young girls who ask her for autographs, saying she hopes they won’t ever have to go through what she’s gone through. The statement she made at Nassar’s sentencing hearing was similar in spirit, and has been widely praised for its poise and strength. Raisman, a two-time Olympian with three gold medals, is part of a new moment, though this one is not about glory — it’s about pain. Twenty years ago, we mixed Kerri Strug’s glory and her pain, and we heralded her for it. This was the legacy many of these gymnasts grew up in; the message was they could do it, and they should, no matter what.

Years after I quit gymnastics, a friend of mine played basketball with the daughter of the same coach who called me out on being afraid. My friend was nothing like me; she was what we now might have second thoughts about calling a loud mouth. After a game one day, she used that loud mouth to ask my former coach if he remembered me. When she started telling me the story, I was sure she would say my name meant nothing to him — I was just one of the many little girls he’d shouted praise and criticism at on the bright-blue gym floor.

But: “Oh yes,” he told her, “I remember her. She was so afraid.”

Even more years later, I realize he’s right. I am afraid of many things. In my adult life, I do plenty of things I’m afraid of and do not wish to do. But now, I know exactly why I’m doing them.

At Nassar’s sentencing hearing, one of the most memorable quotes came from the only accuser who was not a patient. “Little girls don’t stay little forever,” said Kyle Stephens, whose family was friends with Nassar. “They grow into strong women that return to destroy your world.” This is undeniably true, but what strikes me as additionally true is the strength of girls. It’s not that the men in charge of gymnastics perceived those girls as harmless, small enough to abuse, silence, or submit to cruel manipulation. I think these men, from Larry Nassar to Bela Karolyi, recognized and were threatened by the incredible power of the girls in front of them and sought to redirect it back upon the girls themselves. A necessary part of manipulating that power is fear — the fear of being called fearful, the fear of letting down a team, the fear of failing, the fear that makes you run toward a vault like you’re being chased. These girls, these men knew, could work through incredible pain. They could do things they did not wish to do. Once upon a time, we admired that kind of thing.

But in 2018, very young girls know the meaning of me too and time’s up. In the sport of gymnastics, so many adults failed to protect so many children for so long. The heroism of the ’90s was defined by a teenager whose coach challenged her to inflict pain upon herself so she could be the best. You can do it, he said, and she did. More than 20 years later, we have a different kind of hero, just as capable of working through pain but asking how, and for what evil reasons, anyone could want her to do that.