Barack and Michelle Obama looked youthful and vibrant Monday at the Smithsonian, smiling radiantly as they introduced their new official portraits by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald. For many, the moment felt triumphant: the first African-American president and First Lady, portrayed by the first African-American portrait artists ever exhibited in the National Gallery. But a certain poignancy hovered over the joyousness of the occasion, and the paintings are important enough that it’s worth examining why.

Contemplating the Obamas in painted form feels especially bittersweet given the current dystopian presidency. In its apparent mission to kill off as much as it can, as quickly as it can, of Obama’s legacy, the Trump administration has succeeded in making the era of Barack and Michelle seem like the distant past, far longer ago than — wait, was it only last year?

As if sharing this sentiment, the Obamas’ portraits — while infinitely hipper than any others in American presidential history — are also quite sober and unsmiling. Kehinde Wiley is known for blending highly contemporary African-American subjects with classical or Renaissance settings, repopulating the Western art-historical canon with the black figures who have never been there before: A young black man in a hoodie might be depicted as a saint in a stained-glass window, for example.

Wiley’s Barack Obama is also a study in contrasts: seated, but not at ease, perched on the edge of a wooden chair. Dressed for a casual workday, but alone somehow amid a field of perhaps lush ivy. Wiley has painted Obama in muted tones of amber, brown, and navy, but posed him against a background (typical for this artist) of brilliant green foliage dotted with bright flowers. The president’s dark suit says “formal,” but his unbuttoned collar says “off duty.” His widespread legs suggest power and dominance but are also strikingly casual. The body’s stance is attentive, confident, and masculine, relaxed and approachable (arms only loosely crossed, wedding ring visible) but also guarded (protecting his midsection). Most startling is the president’s face, which — in contrast to his youthful, slim body — looks careworn and grim. He gazes at the viewer, but his eyes have a distant look.

And where are we, anyway? Instead of the usual grand, furnished interior, Wiley has placed Obama in a slightly surrealist landscape where vegetation partially obscures his legs and feet. Will the president eventually disappear entirely beneath the leafy overgrowth, like an abandoned ruin? Does this threat explain his troubled countenance? Wiley’s portrait raises these unsettling, implicitly political questions.

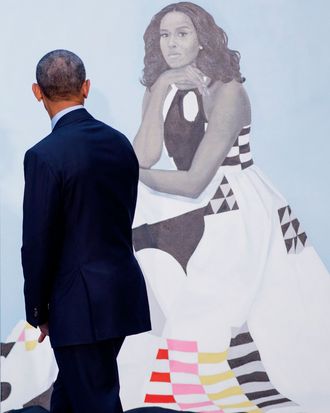

By contrast, in Amy Sherald’s painting, Michelle Obama seems to rise up out of her setting, her face the top of a pyramid whose base is the expansive, flowing skirt of a halter-style ball gown designed by Michelle Smith of Milly — a reasonably priced label, in keeping with Mrs. Obama’s famous fondness for approachable fashion. (This is not the stuff of haute couture, but stretch cotton poplin, “a worker’s fabric,” according to Smith.)

The mostly black-and-white dress is punctuated with geometric patterns and flashes of color which create great visual energy and movement, reminiscent of a Léger still life (the artist says the pattern reminds her of Mondrian as well as of the quilts of Alabama’s Gee’s Bend, a community of black artists). The wearer sits calmly, her face and body rendered in gray scale — without any color. Her upper body flows in arcs: Her softly curved right hand under her chin echoes the position of her left hand, draped over her leg — together the two arms limning an off-center, tilted heart shape. Her waved hair further echoes the painting’s curves. We see little jewelry, only a wedding ring and one pearl earring.

Despite — or perhaps because of — this extreme simplicity and limited use of color, Mrs. Obama emerges here as a figure of both glamour and determination. While styled for evening, she looks far from festive. Her direct, closed-mouth expression is solemn, with a hint of defiant questioning, eyebrows raised, eyes slightly wary, as if to say “What disturbing thing am I seeing?”

Sherald shows us only Mrs. Obama’s upper body, although the gym-toned arms — the famous “guns” whose exposure so riled conservatives — here convey muted rather than muscular strength. And as with Wiley’s portrait of Obama, it is the face that startles — in this case because Michelle does not look, exactly, like Michelle. Sherald has not turned in a portrait of photographic realness. Instead, the face evokes “Michelle-ness” rather than replicating her features. (Gone, for example, are the trademark high, inverted-V eyebrows.) Critics have already noted this, and many FLOTUS fans have registered their strong disapproval.

But with this decision, Sherald declares her artwork more than the portrait of a single woman. This becalmed, majestic figure feels like a monument or a memorial, an avatar of female authority whose glamour, while alluring, telegraphs depth rather than surface. In fact, with its gray tones, the sculptural, lapidary quality of face and flesh, and the way the head and shoulders emerge from a triangular, mountain-like shape, the composition conjures thoughts of Mount Rushmore. Perhaps Sherald implicitly lays claim here for just such a historic, formerly all-white, all-male canonical setting for her subject, granting her a kind of immortality in painted stone. At the same time, none of the presidents on Rushmore bears the kind of perturbed expression Mrs. Obama wears here.

And note the placement of the only colors on this canvas: down at the bottom, near the hem. Is color seeping out of this picture, out of the world once occupied by this First Lady? Is everything turning slowly to gray in a process more ominous than the usual cycle of normal human aging? The picture contains this possibility.

While they may not have conferred with each other, both Wiley and Sherald — in their distinct ways — have presented us with pictures of double significance: tributes to strong, pioneering, and iconic figures of the recent past, pictures worth celebrating for their modern, iconoclastic styles and subjects, but also, portraits of two handsome and magnetic people now reacting to some kind of encroaching disturbance, responding to a world threatened by neglect or petrification.