When you’re in the midst of a revolution you often can’t see it. I was new to fashion in 1988, and pulled in different directions at once — by the subversiveness of Gaultier and Mugler, by the extreme magic of Yamamoto and Kawakubo, by the new uniform of Helmut Lang, by Chanel and the glamour of Paris itself. So I missed Martin Margiela’s first show, held October 23, 1988, at a cafe-theatre in the Marais.

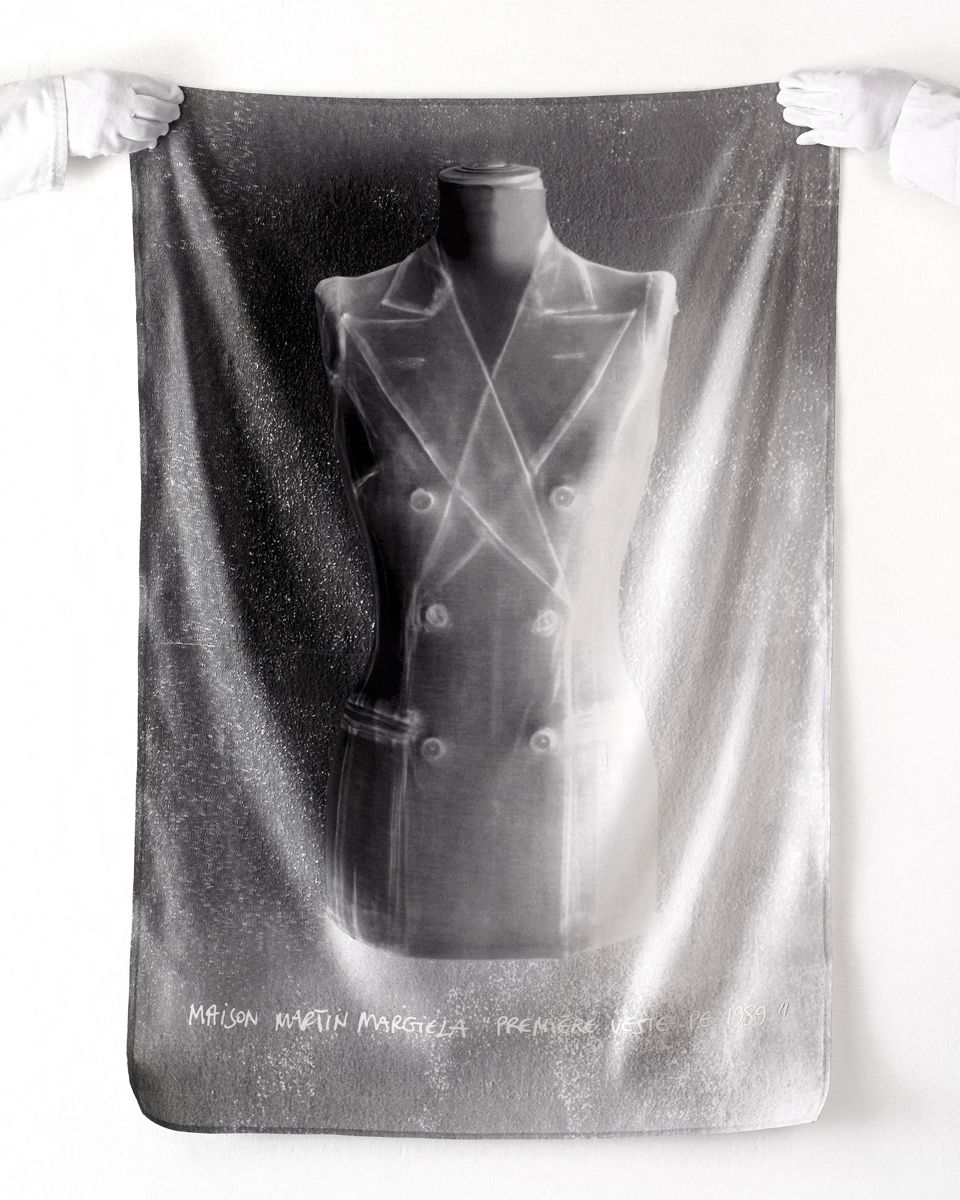

At that show, like the 20 that followed over the next ten years, Margiela introduced the ideas that would constitute his “manifesto,” as a career retrospective at the Palais Galliera refers to that incredible early period. These ideas included not only his explorations into tailoring — really, deconstruction, a term he introduced into fashion — and pioneering use of reclaimed materials such as silk scarves, but also a new system of presenting fashion. He introduced a sense of underground mystery to shows, sending cryptic invitations by fax or telegram to unlikely locations like an abandoned Metro station. At the first show, the models — who were attractive but hardly looked or acted like runway mannequins — paraded through the theater and onto a white canvas-covered stage, where some of them left red marks from the paint they had intentionally stepped in backstage.

Margiela literally took us places we had never been before. I probably saw my first Margiela show in his showroom, in March 1991, but the one that sticks in my mind was at a Salvation Army store the next spring. I sat on a washing machine, and the models wore long black knits and dresses, some covered with dry-cleaning bags.

The exhibition (which does not include the women’s designs Margiela did for Hermès from 1997 to 2003) is a life-affirming treat, remarkable in its insight and detail. Credit for that goes to the great Olivier Saillard, who recently resigned as director of the Palais Galliera to pursue a new venture, and to the curator, Alexandre Samson, who spent a year working out the details with Margiela, who was involved from the start. In fact, it was Margiela who styled the mannequins’ wigs, who painted suntan marks on their limbs (to mimic the effect in the first collection), who put red shoe marks on the floor, and who created the “fan bedrooms” that are part of the exhibit, filling them with books and objects that were pertinent to his creative life.

Considering that Margiela was invisible to much of the fashion world throughout his career — he always refused to give interviews or be photographed — it’s fascinating that he feels so present in the Galliera space.

“He was here until last night doing the makeup for the mannequins,” Saillard told me on Thursday. “You can feel him in the exhibition — you can recognize everywhere the print of his hands.” Saillard laughed. “I did nothing, he did everything.”

Despite Margiela’s policy of anonymity, he has very much kept close watch on the fashion world in recent years, says Saillard. “He’s very worried about everything that’s happening today. He said, ‘Designers forget clothes. They are just interested in images. But they forget clothes.’” Samson and Saillard also found Margiela quite eager — obsessed, really — to explain things, even down to the exact placement of a belt on a pair of trousers.

How does all that square with a man few fashion people have ever seen or heard from? Saillard, after a moment, replied: “I’m still very curious about this attitude, which is probably modest but also you have to know you’re a great talent to do that. You cannot disappear if you do not know you have a great, great talent.”

On one level, the exhibit affirms what a giant influence Margiela’s designs — his lean silhouette, his narrow shoulder-line with a slight peak where the sleeves are set, his use of linings and recycled things — have been on brands, from Celine to The Row to most obviously Vetements and Balenciaga, both of which are overseen by Demna Gvasalia, who worked at Margiela in the latter years.

Yet what I took away from the show — which includes 100 silhouettes, videos, and many documents — was how passionate Margiela was about clothing. That’s not as stupid as it sounds. I didn’t realize, for example, how important Edwardian dress was to him, especially tailoring and perhaps, as well, its use of linings and other underpinnings. A clue can be found in one of his “fan rooms,” where a book on Edwardian fashion sits on a shelf.

Margiela was so fascinated by clothing, especially ordinary off-the-rack stuff, that he reproduced vintage suits and other styles for a line he called “Replica.” Two such items, from Germany in the ’70s and Belgium in the ’40s, are on display. “They’re exactly the same as the originals,” Samson told me. “With the same defects, the same disproportion.”

Perhaps that’s why people over the years have noted that Margiela’s fashion seemed to have the “memory” of other clothes — a quality also frequently ascribed to Sally Mann’s photographs of places in the South. It was extraordinary to see examples from the spring 1996 collection in which minimally cut dresses in fluid or transparent fabrics were printed with negative photos of clothing, so that the image of a dress appeared to give volume to the actual dress.

For me, though, the most stirring display — certainly the most solemn — was of a masculine wool jacket. Viewed from the back, its sleeves had been slightly bent at the elbows, like a person standing elegantly with her hands in her trouser pockets, and then stitched entirely to the body of the jacket. That pose, embedded in our mind’s eye, was embedded in the coat.

Margiela sold his business in 2008, which was the only time the house furnished editors with notes for a show. It was one sentence: “Twenty years, forty shows, hundreds of garments, what’s left?”

Today, at a moment when the fashion industry seems to be asking itself that very question, the Galliera show seems well timed. It also puts perspective to Margiela’s genius. He did many of those early shows on a thin shoestring, in contrast to the usual practice of spending a small fortune, and he and his business partner, the late Jenny Meirens, came close to bankruptcy. In other words, Saillard said, it wasn’t about having a financial structure, or a good stylist, or the right editorial connections.

“It was about having ideas,” he said.

“Margiela Galliera” remains open through July 15, 2018. It’s part of “Saison Margiela 2018 a Paris,” along with “Margiela les annees Hermes,” at the Musee des Arts Decoratifs, from March 22 to September 2, 2018.