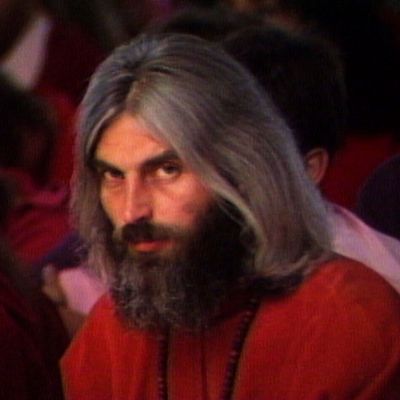

Throughout Wild Wild Country, the buzzy new Netflix docuseries about followers of Indian mystic Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, there are a number of characters whom we meet via archival footage, yet whom directors MacLain and Chapman Way chose not to interview in the present day. One such character is Bhagwan’s British-born personal physician, referred to in the series as Swami Devaraj or Dr. George Meredith. When I spoke to him on the phone from India recently, however, he told me that he now goes by either Amrito or Dr. John Andrews. “It’s really complicated,” he acknowledged with a laugh. (Per a Netflix spokesperson, the directors “just couldn’t make [an interview] work with timing and the production schedule.”)

Andrews was a member of Bhagwan’s inner circle in Rajneeshpuram, the group’s short-lived Oregon commune. As the series reveals, Bhagwan’s ruthless deputy Ma Anand Sheela attempted to have Andrews killed, ordering her accomplice Jane Stork (then called Ma Shanti B.) to poison him with a shot of adrenaline to the buttocks. Currently, Andrews serves as vice-chair of the Osho International Foundation, a Switzerland-based nonprofit which owns all of Bhagwan’s (now called Osho’s) intellectual property and continues to run a vast meditation resort in Pune. Yet the doctor continues to be a controversial figure within the Sannyasin community. Andrews was one of the few people with Osho when he died, and the exact nature of the master’s secretive death remains the object of speculation (at least on Sannyasin message boards.)

Likewise, there have been allegations of financial wrongdoing, including the possible forgery of Osho’s will. Not discovered until 2013, the document bequeaths all his property to a Swiss trust overseen by Osho International Foundation board members Andrews and Philip Toelkes (a.k.a. Swami Prem Niren, the true-believer lawyer from the documentary). Rival groups of Osho followers have challenged the validity of the will, and the legal battle is ongoing. As Kenny Herzog writes over at Vulture, “Wild Wild Country didn’t delve into the minutiae of postmortem infighting over the guru’s estate, but there is enough drama in the fallout to merit a sequel.”

Speaking to me on the phone from India, Andrews, who has a posh British boarding-school lilt, wanted to extol the value of his leader’s teachings and criticize the machinations of Sheela (as you’ll recall from the Netflix series, those included poisoning, arson, and attempted murder). We discussed what Megyn Kelly doesn’t get about Osho’s legacy, Sheela’s “tough titties” attitude, and why a murder attempt wasn’t enough to draw him away from Osho’s side.

The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Did they ever reach out to you to be in the documentary?

No. I wasn’t contacted.

How did you feel about that?

I think there are a few things which really got kind of overlooked which would’ve been nice to have been able to articulate, really. But, you know, they had lots of people talking. I don’t think they needed more talking.

What would you have wanted to add?

I mean, in a way, Osho’s really not a central part of the documentary at all. If you wanted to really tell the story properly, you’d want to know something about Osho, right? And all the coverage in a way totally misunderstands Osho. I saw Megyn Kelly the other day — it was actually disgusting, really, in terms of misrepresentation — she did an interview with the two guys who did the documentary, and it was kind of, oh you know: these ridiculous cultists, sex all the time, they were killers — sort of just pure misrepresentation. Well, hang on: You don’t say all of Chicago are killers because Al Capone lives there. Another thing is, [the reason we initially went to Antelope is] that we couldn’t get a phone line [where we were]. That’s what it came down to. It wasn’t this invasion of Antelope. I mean, who wanted to go to Antelope? Who in the hell wants to go 19 miles away from your friends, it took 25 minutes in a pickup on a really bumpy road.

Right.

There was no reason why [Oregonians] couldn’t have just left that community alone. They weren’t interfering with anyone’s lives. And in fact, turning a piece of barren desert into an oasis, that’s not a bad project. When you look at the world today you kind of wish there were a few more experiments like that going on.

In a way, that seems like why the documentary is really resonating with people. People are watching it and saying “Well, the actual utopian ideal of Rajneeshpuram looks kind of appealing” — although of course there was this very ugly and awful stuff that was happening behind the scenes.

Let me just clarify that. The other part of the story which is really not clear, but you could pick up on it, is that over a period of time, basically Sheela split from Osho. She openly said, “I’m not interested in meditation at all.” So you’ve got a non-meditater trying to understand the vision of someone whose only interest is meditation. That’s a pretty strange starting point. And then, basically, she starts saying: “He’s lost interest in his vision, but I know what his vision is and I’m going to be the one to deliver it.” As time went by, she really started to push back and not do anything Osho wanted. By 1984, she’s really kind of going off the rails, really.

Why didn’t you leave after the murder attempt?

I would never have thought of leaving. I’m there because this is the most amazing experiment ever, and primarily I’m there to be with Osho. So I would just do my best to keep my back against the wall, you know?

Sheela has definitely been this sort of object of fascination, I think, for people who’ve watched the documentary. Can you give any insight into what kind of person you think she is based on the time you spent with her?

Definitely courageous. No question. She was this kind of high-powered, fast-moving, quick-talking, quick-thinking, intelligent, courageous, go-getting person, and everyone went “Great! This is wonderful.” By sort of early ’81, Sheela’s really everybody’s favorite. It’s we who chose Sheela, and Osho who crowned her. And she’s an incredibly able administrator, able to get things done. Yet she had no sense of Osho’s vision. She thought Osho’s vision was to create a community. But Osho’s vision was to help people become themselves. He’s not interested in creating an alternative society. He’s interested in people who go into the normal life and live beautifully wherever they find. In my opinion, what Einstein was to the 19th century, Osho will be to the 20th century. Instead of being about the outer cosmology, it will be about the inner cosmology.

Did you ever see the movie The Bridge Over the River Kwai?

I haven’t seen it, no.

It’s sort of similar where this person just gets completely obsessed with what they think they’re there for and then lose all sight of what they’re really there for.

Why was she so out for you? She claims that you were planning to give Osho euthanasia and that you had got him addicted to drugs and so forth. Is that all a lie? And if so, why did she try to have you killed?

Yeah, of course. The key was, she attacked his household and everybody in it and found any excuse she could to do that. She constantly hated the fact that we had access to Osho. We were a constant threat to her total monopoly on power.

Were you frightened during all this?

No, not really. I mean, you know, I wasn’t dead, I’m alive.

To what extent were you aware of the stuff that was happening in the wider community? You know, the salmonella poisonings and the assassination attempts.

No one would have dreamed of it. She had a very, very little tight community. No one had a clue. By the time she left, everyone was horrified. It was kind of a pretty major moment. She just got in that plane and, I remember, she flew off in the middle of September. That was it, she was gone. Everyone’s like “What?” Like the fall of the Berlin Wall, you know? “Wow, she’s gone!” “Hey, it’s party time.”

I’ve talked to a lot of people who were on the commune and there are sort of mixed feelings about the film. What was it like for you to watch the Netflix version of it?

Some of it was very beautiful. Though you didn’t really quite understand how it sort of got going to start with. They lay a very beautiful foundation of the background, but the specifics were a little loose. Let’s start with “guru.” What is a guru? Osho has spoken against gurus and religious leaders, and [against] this game of hierarchy and how God is the ultimate dictator and this endless business of creating middle men. He’s very precisely clear, “My whole effort is to leave you alone with no mediator.” You’re here because of your interest in meditation. You’re not here to be friends with each other. You’re not here to create some group. You’re not here because of each other, you’re here because of yourself. The bridge is single-file. So the whole idea of a cult is absolutely antithetical to everything he presents.

Then [this notion of] a sex cult, I mean … Osho’s understanding is very simple: [Sexuality is] your vital life energy. Very simple. And it’s completely natural. In order to grow spiritually, whatever you wanna call that, you cannot repress sexuality. One thing that he was very, very strong on was giving responsibility to women. That was, in a way, the most beautiful thing.

Sheela, oddly enough, has kind of become this feminist empowerment meme on the internet.

Yes, I saw all the “tough titties” stuff all over the place. She was strong. I mean, as a woman, she would take no crap from anybody. In today’s world, good on her.

Were you able to feel any sympathy for Jane, who is sort of the only character in the story who seems to feel like she was sort of brainwashed and then later deprogrammed?

Well, you’re watching someone who’s completely unconscious. She was unconscious then, and she’s unconscious now, and all you can do is look at this person and go, “Well, you were dumb then, and you’re dumb now.”

Also, by the way, we haven’t mentioned the other famous subject: of course, his Rolls-Royces. He thought: In a society obsessed with stuff, I can write, I can produce 600 books on meditation and no one is interested. But Get 93 Rolls-Royces and the world will never forget. Basically, here is this nonwhite male from India who wears a robe and a funny hat, and drives around the city where everyone wears red and doesn’t get paid, they’re all vegetarians with no interest in the family or private property, right in the middle of cowboy country — you could see how the inevitable game unfolds. But by having cars, and driving these cars, and having 93 of them in the country which has the biggest and the best — you know, ‘make America great again’ — if anyone’s going to have the most cars, we have to have the most cars. And here’s the nonwhite guy, he’s got more cars than we have. So it turns into kind of a joke about consumerism. Fantastic.

I know there’s been some controversy about Osho’s death and that you were with him at the time, with some people alleging that there was foul play involved. Can you give your own account of what happened?

So I’m saying to him, “We need proper intensive care now, should I call the cardiologist?” And he says, “No, existence has its timing.” So then you’re a doctor sitting there, like “Well, the guy say no to any further medical intervention and it’s his body and one thing he’s always been quite clear about, everyone has a right to their own body, no one else has any right to interfere.” When people go, “Someone must have killed him,” it’s like, that’s such crap.

Did you ever feel that your ethical duties as a doctor conflicted with your devotion to Osho’s teachings?

No. He was really scientific. I mean, in a way, this is a really funny role, but in a way I was a research assistant, that’s really what I was.