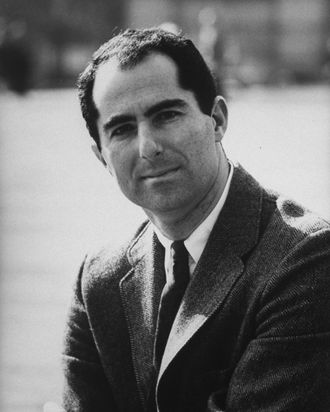

A few semesters ago I taught an undergraduate seminar on first novels. I was called in to teach it at the last minute, and, while I was allowed to make up my own syllabus, I wasn’t given any guidance about what, exactly, made “first novels” a worthy subject, or even what aspect of them I should be focusing on other than their first-ness. I was relatively new to teaching and so I composed my syllabus by scanning my bookshelves for first novels I thought would be interesting to reread. I hesitated before including Goodbye, Columbus, in part because I figured everyone would already have read it.

As it turned out, no one had; no one had even seen the movie. A couple of students had been assigned Portnoy’s Complaint, but no one had read any other Roth novels. They weren’t avoiding him on purpose, either, as I had been at their age. They just kind of … had no idea who he was. And this was at Columbia, a stone’s throw from his apartment! But this was for the best: Coming in with no preconceived notions about the book or its author, my students responded to it in a way that surprised and delighted me.

It’s so crazy that this is a first novel, by the way. It’s a preternaturally tight and polished 136 pages that manages to be both dialogue-driven and full of acute, epigrammatic physical description. If you’ve read it, you probably just remembered one or more of its indelible images: Brenda’s sleek head breaking the surface of the country club pool, the Patimkins’ basement fridge full of chilled, gleaming fruit. With perfect economy, Roth delineates a hate-laced love affair between an ambitious but struggling striver and a Radcliffe student from a family that’s a generation removed from that struggle, both of them New Jersey Jews. The class-based gulf between Neil and Brenda — its historical sources, the way such rifts rippled out into American culture for several generations — was totally boring to my students. Even though most people would say that’s what this book is “about,” and indeed what many of Roth’s books are about, that was just not what they were interested in.

Instead, what they took away from this book was a sense of permission. After they read it, their reading responses and creative assignments became markedly less stilted and academic. They not only became more comfortable saying how they felt, they also became more agile at describing their feelings, and even at tracking down some of their feelings’ sources. Roth’s frankness, which he makes seem effortless, emboldened them to be frank, and to be a little bit more ruthless. They started, thank god, writing dialogue in big chunks without interruptions for narration or superfluous “he explained patiently”–type attributions. Without my having to explicitly teach them much of anything, they took away something essential from reading Roth: the idea that fiction does not have to be plodding or dutiful — that if you’re bored, the reader is probably also bored, so you can go ahead and skip a long description and trust the reader to fill in the details. You can even trust the reader to take what they need from the text when they need it.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised by this response. In many ways, the students’ experience mirrored the one I’d had when I finally came around to reading Roth in my late 20s. Before that, I had lumped him in with Mailer and Bellow and Updike, authors whose technical skill I could admire — just barely — even as they made it clear in every way that I was not their ideal readership, and that I was in fact sort of a garbage human, a lesser variation on the male of the species. But this wasn’t my experience with Roth, even as his narrators often perceived women primarily as objects of lust. Instead, I felt invited in by a stylist who was above all an entertainer, a generous writer who was never ostentatiously, self-consciously virtuosic. His perfect ear for speech conveyed an interest in all kinds of people that transcended his cruel streak. If his portraits verged on satire, it was only because his subjects were so intent on making fools of themselves.

My students, lucky them, got to skip over the step of considering Roth a problematic fave; they went straight to just “fave.” Reading further into his canon might complicate their early assessment, and of course I hope it does; complicated feelings are the best kind, and their reading will make them better able to articulate these feelings as they arise.

Now that oeuvre contains a last as well as a first novel. I’ll continue to teach Goodbye, Columbus; I hope my students will continue to find it resonant, but even if they don’t, I’ll still get the pleasure of continuing to reread it, finding something new to admire or be enraged by, or both, every time.