My sister and I headed out at 6 a.m. on a sunny day that promised bright Lebanese summer heat. We sipped our coffee silently for much of the ride, looking out a car window at the highway snaking up the coast of Lebanon, the mountains rising up quickly to our right, the rocks at our left dropping sharply to the sea. Neither of us wore makeup that morning.

We were driving from Beirut to Tripoli’s Beddawi camp, one of the oldest and most densely populated refugee camps in Lebanon. Both of us were dreading the experience — we had been through displacement as children, when we fled Lebanon as refugees to Canada in the mid-’80s. But we knew that for the generations of Palestinians, along with newly arrived Syrians, life at Beddawi was much different.

The camp was established by UNRWA in 1955, as the first flow of refugees came fleeing Israeli expansion in Palestine. Though only one square kilometer, it is a functional city of almost 20,000 people. Houses, roads, makeshift electricity and infrastructure have all sprouted up and evolved over the years with little help from the municipalities outside the walls. Entire generations have been raised in the enclosure, without rights to citizenship or work in their country of refuge.

We parked the car next to a broken-down rusty Ferris wheel, probably installed by an international NGO for refugee children during some earlier epoch. Our first stop was the a job-training school run by ANERA, American Near East Refugee Aid. “Beauty and makeup class is one of our most popular courses in the program,” said Maggie Forster, ANERA’s vice-president of philanthropy.

We were greeted by the program’s teachers, organizers, and star students, all of whom had perfectly drawn eyebrows, kohl around the eyes, and heavy foundation. “Around 95 percent of refugee girls are out of school,” Forster explained. “A lot of the girls who have taken the beauty and makeup course are now working as beauticians or opening their own shops, which allows them the flexibility of working out of their homes.”

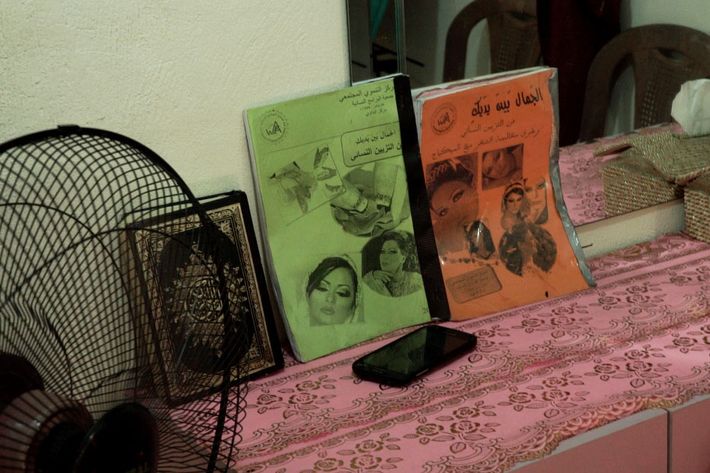

Part of a larger education facility for boys and girls aged up until their late teens, the fashion and beauty program’s space includes a cut-and-sew atelier, a makeup table, all their cosmetics and lipsticks. In the camp’s busy streets, we met Samara Khalife, a 24-year-old Beddawi resident who had recently graduated from ANERA’s training program and opened her own beauty parlor. She invited me to sit down on the chair to get her signature eyeliner. “People come from all over Tripoli to get their makeup and hair done by me,” said Khalife.

I was raised to believe that self-care is an intrinsic part of Arabic culture. For most women, knowing how to groom yourself and celebrate your femininity — to an extent that even makes me uncomfortable, at times — is a core part of being from the Middle East. Both of my Lebanese grandmothers are still alive, and they tell me about self-care every chance they get.

Taking good care of myself and being beautiful, they say, is part of my duty as a woman. I enjoy the celebration of self-care and self-love, but the “duty” part can make me uncomfortable. I find in all cultures, women have a fine line to walk between loving themselves and performing for the male gaze. But when I show up with my hair undone and without makeup, they take offense, as if I’ve given up on myself. Sometimes I feel like I have.

Their beauty routines have always been simple and natural: they wash their face in the morning with Aleppo soap, followed by almond oil as a base for everything. To keep their skin smooth and hairless they make sukar — sugar wax — at home as a depilatory concoction. The first time I was allowed to remove any kind of hair from my body, my grandmother did it with sukar, and I screamed in pain. The first time I was finally allowed to pluck my eyebrows, my mother did them perfectly. She kept them thick and explained, “This is how they need to stay, understood?”

Everything my Lebanese relatives, and especially my grandmothers’ generation, use for beauty products returns to nature as food, not as poison. They do facial and body peels with a pumice stone, or a pinch of baking soda mixed with water. They color their hair with henna, a plant dye, and apply homemade rosewater to their faces in the morning, to soothe redness. “Boil artichokes and drink the water to lose weight,” my Grandma Souad suggested after I had given birth to my first daughter. This is what my grandmothers have taught me, to the exasperation of my mother, who loves anything she can find in a Sephora.

After the civil war, the Lebanese notion of beauty became distorted — at times, it was the only mechanism available to feel in control of one’s self. Both extremes are now present in modern Beirut: the beauty standards of the Kardashians on one side (Lebanon has a very high rate of plastic surgery), and a rebellion against postcolonial aesthetics on the other, in which women embrace their body hair and natural hair. Still, whether we’re going to the grocery store or a party, we dress up, and we wear makeup. Beauty is something we can control, love, and celebrate. It is, at some of the worst times, all we have left.

For my second trip to Beddawi, I went armed with a camera and a notebook. I wanted to record stories, to connect with the girls there and talk more about beauty, a subject that made them glow with pride and dignity. The Palestinian refugees I met in Lebanon talked about beauty and self-love as acts of resistance.

One young teen I befriended, Amal (which means hope in Arabic) told me, “There is makeup for every occasion of the day. Maybe you are sad and just going to the store — I suggest a little mascara to change your mood. Or if you are getting ready for a party or to celebrate a wedding, eyeliner heavy on the eyes is important to make you feel elegant.” This was makeup as a coping mechanism.

“In the media, refugees are portrayed deprived of their dignity, without any beauty left in them,” said Skylar Lawrence, ANERA’s director of donor development. “This is far from how we have experienced working with them,” she said. In the refugee camps I visited, beauty was not considered superficial, especially when used in the act of reclaiming one’s dignity and self-worth. In the face of adversity, looking and feeling good had become a human right — the right to celebrate one’s self.