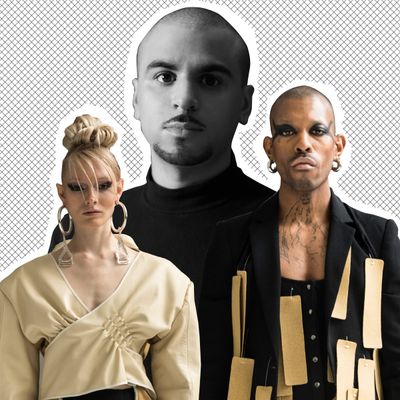

Solange and Rihanna have both worn designs by young Dominican-American designer Raul Lopez, and the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund has named his label LUAR one of their ten finalists for 2018. But Lopez, who showed his SS 2019 collection yesterday, has set his sights higher than a career as just another designer: “I want to leave a legacy when I die,” he tells the Cut.

On a sunny Thursday afternoon six days before the show, I met Lopez in his workspace in the West 30s, where pattern-makers and workers were crafting all-white looks for the new collection. I’m floored by an ethereal sheer white gown hanging on a bust form in the corner.

“LUAR is me,” says the Latinx designer and Brooklyn native. His sartorial roots date back to his seamstress grandmother from the Dominican Republic, who arrived in the late ’50s to work in a factory on Astor Place. She was followed by more family members who worked in the Garment District in the ’80s.

LUAR is laced with Lopez’s trajectory: his youth in Los Sures (otherwise known as the south side of Williamsburg, Brooklyn), his Dominican Yorker identity, ballroom culture, hip-hop, and queerness. Lopez first gained the attention of the industry as the co-founder, along with Shayne Oliver, of the streetwear-influenced, gender-deconstructing fashion label Hood By Air, and LUAR takes his fantastical genderless hood aesthetic in a personal direction. Below, Lopez talks about his background, the Hood By Air blueprint, and telling his solo fashion story on his own terms.

What was it like growing up in a Latinx household in Los Sures in the ’80s and ’90s?

I draw a lot of inspiration from my upbringing, and Los Sures, which is now gentrified Williamsburg … it was crazy. It was an era where it was just crack. There weren’t really a lot of Dominicans around there. My dad was the super of the building for like 21 years. My parents moved out, but I still live in that same place where I was born and raised in Brooklyn.

Back then there was a lot of artists who were white, as well. They moved from the East Village to Los Sures, and they’re still there, they still live on my block. My dad owns a construction company and he does business with them. I think that influence from the Hasids, the Latin culture, the hip-hop culture, the artist culture — all that has molded LUAR. I’m always tapping into my past but bringing it into the future.

Talk to me about sexuality, fluidity, and fashion inspiration from the Dominican Republic.

It’s the most fluid country. I’ve always been such a flamboyant boy, and there I feel glorified for that. I dress gayer and more flamboyantly and more fluid in DR that I do here. Here, if you walk in a lot of places, you get looked at, you’ll be called a faggot, you could probably get jumped. In the Dominican Republic, it’s the total opposite. It’s like the more flamboyant you are, the more they accept you. They have Pride. They have one of the largest Prides in the Caribbean and in Latin culture, it’s huge. They do one in the capital (Santo Domingo), they do one in Santiago, they do one in Santa Cruz de Mao, they do one in like a couple of other cities. They feel if you’re gay you’re creative.

When I parted ways with HBA, I started doing a line called Luar Zepol. I was doing it in Dominican Republic because I was like Let me go back to my roots and be inspired by where my family is from. I would ride around on a motoconcho; I wouldn’t ride in any cabs, no Ubers, no nothing, it was literally always on a motorcycle. I wanted to absorb everything like a sponge. My job is to look, so I can be inspired. So I was taking what I saw and inverting it into this subconscious LUAR person.

And I was trying to get back to tailoring, because they are very known for tailoring and seamstresses in DR. That was my movement of shifting from HBA to LUAR.

You’re a Dominican Yorker who navigates uptown, the downtown club scene, and the ballroom scene. How have those experiences shaped you?

Being born-and-raised in New York, coming from the hood, the only thing that was available for kids that were gay in the early ’00s was Christopher Street. I would take my clothing around in my backpack and get dressed in the West 4th train station by the West 8th side, all the way on the back on the A train, so I could walk out with my outfit on and go onto Christopher Street. Once I started going to Christopher Street, I started getting more comfortable in my own skin. Then I started meeting people from the ballroom scene. That’s also how I met Shayne.

There used to be a club called the Club House Uptown at the Karate Club in Harlem. They had balls every single Thursday. I went there every Thursday from midnight to 7 a.m., every week from Brooklyn. I was staying on Christopher Street to like 2 or 3 in the morning. I remember I even slept on Christopher Street. I couldn’t go home. I was scared; I was hiding not just from my family but from the neighborhood. So I think that I also built this tough skin and exterior that I have.

A lot of people think I’m like this sassy girl. You have to understand, I come from New York. I’ve been punched in the face, beat up, picked on, ridiculed, bullied. You guys have it easy now, you have laws. There was no safe space. There was no social media. It was just every man for themselves. So I had to build this tough skin and incorporate it into my everyday life.

I started dressing to fit in with everybody — kids from the hood, kids that were punk, kids that were flamboyant. And that’s how me and Shayne kind of gravitated to each other. We both came from Caribbean backgrounds, from Brooklyn, believed in the same looks. He came up to me and he was like “I think you’re fab, let’s ki,” and then it was history. That was our story. then LUAR comes and I just felt like I needed to say my own story.

You’ve said that HBA was your baby. What are some of the lessons from HBA you transferred to LUAR?

HBA was a good movement in my life. We were shaking things up, saying things about gender that weren’t being said. But I feel like it was a stepping stone to get me to LUAR. When you come into fashion, you need to be a businessman before anything. We didn’t know that. We just loved fashion; we wanted to shake things up.

It’s the baby effect. You give birth to something, you nurture it, you feed it, you give it your all. Then the baby starts gibbering, then it starts crawling, then it starts walking and talking, and then it goes to school. I feel like that’s how a brand is. You need to give it your whole entire all, so it can work. Because if you don’t, it’s not sustainable. And right now sustainability is like the biggest thing for brands.

Steven Kolb said this: “Sustainability is not just about the clothing, it’s about the culture and the history behind it.” I feel like a lot of people are buying into what they see on Instagram, as opposed to what the brand really means. When I design, I design for people who are confident enough to feel comfortable in their own skin. It’s not just “Oh yeah, I’m making clothing.” This is my story, so when you buy one of my pieces you’re buying a piece of my story.

You are now three collections into LUAR. What does the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund accolade mean to you?

I didn’t go to fashion school. I’m self-taught. I feel like the CFDA even picking me is truly humbling. Coming from New York, being so inspired by the fashion industry, sneaking into fashion schools to go into their libraries, researching at the public library — after all that, this is like my graduation. It’s affirming all the trials and tribulation that I had growing up, with designing, and my life as a Latino boy in New York.

I need it to make me sustainable. I’m funding myself; I’m hosting parties just to make some cash. I’m not getting funding from family. And I feel like it’ll give a voice to people who come from my background. If you have talent, you have to push and strive. A lot of times, if you come from a Latino background or a POC background, your family wants you to get a blue collar or a white collar job, to fit in with the norm. I chose not to.

With the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund’s help, I will be able to fund myself, to build a team, have production, get that business background that I couldn’t get from school. I’ll be able to ask all these major people, “How did you build your brand from the ground up?” Also getting mentorship from designers and seeing their creative process — I think that is the biggest gift you can get, apart from just the money. You need to know what you’re going to do with the money. I have a whole list of where I need to go, what factories I need to talk to, who I need to hire.

I want to die a legacy. I don’t want to die somebody who just made clothing. I want to be like the people I look up to, the Gallianos, the Gaultiers, the Chalayans, the Alaïas. These people will be remembered forever. I want to win this prize so I can leave a legacy when I go.

LUAR is autobiographical, and it’s an intersection of NYC, DR, technology, and the future. What inspired the new season?

The theme of SS 2019 is Purgatory. That’s why the palette is all white. It’s paying homage not just to Catholicism, but Santeria (which I don’t practice). It’s all the stuff that comes from my Latin culture. You go to my grandmother’s house and it’s full of saints.

I feel like we all live in a purgatory right now. We’re not in hell; we’re in that layer where everybody’s fighting to get to the top. Everyone wants to be right; everyone wants to be saved. With this season, I wanted to create something that resembled what’s going on right now. After I did that wedding dress [Lopez created what Vogue called a “purposefully anti-traditional” wedding dress for fashion producer Cynthia Cervantes] it felt like a rebirth, so it kind of has a Renaissance feel to it — taking the Renaissance era and bringing it to today. It’s kind of like Thot-assaiance. Sexy, but more sculptural and more shaken up. It’s a lot of new techniques that I’ve never done. The rebirth of LUAR will be a very clean palette.

This interview has been edited and condensed.