I was never a Burt Reynolds fan. He was very talented, but — with the exception of Deliverance and Boogie Nights — his vehicles usually did not rise to the level his gifts deserved. Instead, he spent most of his career on the lower end of pop culture, in light comedies and action films like Smokey and the Bandit. He starred in mediocre television, including his own forgettable sitcom (Evening Shade), and was a frequent guest on talk shows.

Despite all that, when I heard that Reynolds had passed away this week at the age of 82, I was shocked to find myself crying. Not because I was sad for myself, but because to me, Burt Reynolds will always be linked to memories of my late mother. Mom adored Burt Reynolds, and when I was a child I was fascinated watching her watching him. So I guess you could say I was a Burt Reynolds fan once removed.

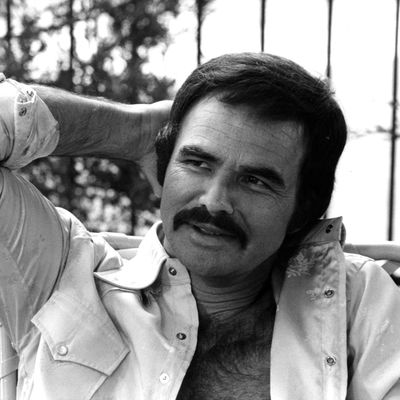

What my mother — and millions of other female fans — loved about Burt was that he seemed “mischievous” (that was her word). He had a devilish smile, and evinced a kind of perpetual, ironic mirth. His expression — whether playing a role or being “himself” on The Tonight Show — seemed to say, “Yes ladies, go ahead, feast your eyes, I’m delectable man candy. Isn’t life a hilarious romp?”

Never was this clearer, of course, than when Reynolds posed in 1972 for that famous nude centerfold in Cosmopolitan — happily submitting himself to the newfangled idea of being a male sex object. A look at that iconic photo explains a lot of Reynolds’s success: Photographer Francesco Scavullo — a man who knew how to frame beauty — turned Burt into a grinning odalisque, arranging his wildly hirsute body on a bearskin, head propped up on one elbow, and bathing it all in Rembrandt-inspired amber light.

The message was clear: This is a warm, embraceable, tamed wild animal of a man, a fuzzy Adonis. The one unmistakable nod to a franker, more overt eroticism was the cigarillo dangling from Burt’s mouth: the perilous accumulation of ashes about to fall from its tip needed no decoding.

Burt’s persona seemed to telegraph sex without menace. Rugged manliness with no suggestion of domination or self-regard. And if you think about it, that is a very rare combination in a movie star — of any era. Reynolds had the twinkly, woman-loving charm of a George Clooney, minus Clooney’s aura of acquired upper-class privilege. (Burt would never have wanted a villa on Lake Como). He had physical magnetism too, the bodily, masculine ease onscreen of a Daniel Craig, but without discernible violence or even petulance. But while he was very good-looking, his round face and exuberant hairiness kept Burt Reynolds just this side of classically handsome. Taken all together, these qualities brewed up an alchemical combination for a unique, nearly paradoxical appeal: approachable allure.

In real life, Reynolds may have been a far darker character — he was accused by both of his ex-wives of abuse. Yet to his audience, Burt gave the impression of an open door, a man’s man who just happened to prefer the company of women (or seemed to, anyway). And in this, he offered his female fans what felt like the key to a secret club.

As for the particular women he preferred, the range only added to his likeability. One of his early public loves was singer Dinah Shore, who dated him when she was in her 50s and he in his 30s — an unconventional age difference that underscored Burt’s catholic tastes and offered an early feminist endorsement of mature female sexuality. Then there was gamine British actress Judy Carne (his first wife); ingénue-turned-feminist icon Sally Field (the one that got away, he always said); and actress Loni Anderson (wife No. 2) — whose over-the-top, Monroe-esque, sex kitten shtick matched Burt’s persona for knowing self-parody. All interesting women, to be sure, but not one was the kind of traditional, self-serious Hollywood beauty you might have expected at his side.

These romantic choices made Burt seem open-minded, even democratic. This was, of course, his carefully crafted on-camera side. If those allegations of abuse were true, it’s possible Burt made women pay privately — and dearly — for his apparent good nature in public.

But whether it was fully authentic or just a very effective performance, Reynolds’s style fit perfectly into the era of his heyday, the 1970s and ’80s, when feminism was hitting its stride, women were pouring into the workplace, and Our Bodies, Our Selves was teaching us that women needn’t conform to narrow parameters of beauty or lifestyle, that sexual pleasure was ours to seek, orgasm was a right, and reproduction a choice. (Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, just one year after Burt’s nudie turn in Cosmo. The Pill had been around since 1960.)

Thinking about this now, I realize that Reynolds’s death made me cry not just for the nostalgia it evoked in me for watching movies with my mother, but for the entire era that Reynolds seems to conjure. Watching the Brett Kavanaugh hearings is enough to make us all dread that the woman’s movement is about to be set back by a half century at least. Feminism feels less like a promise for the future now and more like an urgent battle to keep from sliding backward.

But in those early days of Ms. Magazine feminism, everything seemed possible. American women were envisioning wildly exciting futures. And Burt Reynolds, on screen at least, felt like the epitome of a new kind of partner for a new kind of woman. My mother never called herself a feminist, exactly. But she knew her daughter was becoming one, and she felt the change in the air. I dare say that the attraction that Burt Reynolds held for her contained the possibility of a new way of imagining female desire: more equal, more fun, less constraining.