“There’s certain shades of limelight that can wreck a girl’s complexion.” Audrey Hepburn’s Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany tossed out the line like candy to a crowd of children. Her hands were shaking as she applied her lipstick in the back of the cab and by the end of that line her lips were perfectly orange-red, perfectly lined and perfectly pursed. She was fleeing but she was unmoved from her rituals and so, she was beautiful. Like a doomed doe. Her life was falling apart and she knew it, and what did she do? She put some lipstick on.

Lipstick has been the glue for feminine tragedy for centuries. It has also been an easy codifier for class warfare and a tool used to target women as much as it’s been a balm. This spans civilizations, continents, empires, myth, and reality. Certain shades delineated class background: a hot pink meant wealth and red was working class (long before Marx’s meme of communism entered the picture). Throughout civilizations these colors and their symbolism shifted, but the cycle of respectability and rouge was always around.

In early Greek civilization, lip paint signaled sex work and eventually engendered the onslaught of lipstick regulation: under Greek law, prostitutes who appeared in public at the wrong hours or without their designated lip paint could be punished for improperly posing as ladies. This isn’t so different from the (now debunked rumor of) a 1770 Parliamentary law that banned cosmetics, particularly lipstick, for fear it summoned the devil and was a signifier of witchcraft. And Rome’s last emperor Nero’s wife, Empress Poppa Sabina, retained more than a hundred servants just to maintain her face — those slaves were called cosmetae. Of course, her legion of cosmetic slaves did not protect her from the man’s violence. Nero kicked her while she was pregnant, and both she and her child died. Lipstick as symbolism: beauty is desired until it isn’t enough and becomes repulsive to repulsive men, and then it’s tampered down.

On that note, lipstick was just as often part of women’s efforts toward freedom from the bonds of man. In 1912 when the suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Charlotte Perkins Gillman marched for the rights of women, they wore red lipstick. Rather than beauty exemplifying extravagance, it symbolized the splendor of freedom from social mores. Elizabeth Arden was supposedly there handing out tubes of her own products. I find the image of this happening extremely satisfying and a fitting mirror to the time Coco Chanel passed out bottles of Chanel No. 5 on VE-DAY after WWII as a tactic to avoid getting arrested for her collaboration with Nazis. At least one beauty entrepreneur was on the right side of history with their brand activations. Elizabeth Arden still sells lipsticks for feminist charity work.

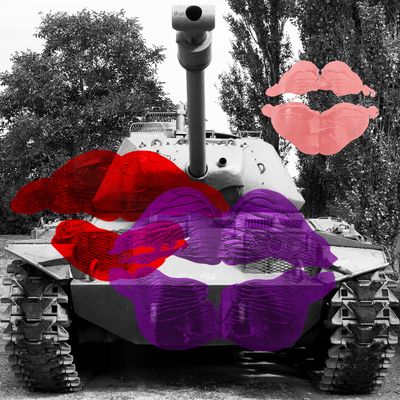

The war made beauty into a tactic for everyone, from collaborators to spies to housewives (not that you couldn’t be all of the above at once). In the U.S, the War Production Board restricted the production of certain cosmetics in an effort to save metals and chemicals for the war. They hoped to reduce production 20 percent but so many people protested that the decision was reversed in less than four months. They not only reversed it, they backpedaled and affirmed that cosmetics were “necessary and vital to the war effort because of their potential to boost morale.” Brand campaigns heralded that “beauty is your duty,” and the brand Tangee issued an advertisement that said, “war, women, and lipstick — for the first time in history, woman-power is a factor in war … a woman’s lipstick is an instrument of personal morale.” Helena Rubinstein explicitly designed her packaging to look like a bullet. Women were encouraged to send letters covered in lipstick kisses to boost soldier’s morale. Elizabeth Arden was even commissioned to create a makeup kit for the Marine Corp’s Women’s Reserve. Victory Red, Montezuma Red to match the color of the uniform scarves.

It may have been a few decades but beauty is still used as a tool of political propaganda and morality. Some things haven’t changed at all: several brands still design their lipstick packaging to look like shotgun shells, and brand owners and distributors still donate their profits to political organizations they find useful. Longwear lipstick brand Lipsense’s distributor Ben Kante was a top donor for Trump’s Inauguration Committee, after all.

Sometimes the symbolism of what lipstick can and should do isn’t explicit at all, but it still wounds. I’ll never forget reading one such example. Guerlain’s creative director Anton-Philipe Hunger once said: “We didn’t want our lipstick to click so loudly that it would draw attention to a woman who’s touching up in public.” So they test-clicked between ten and twenty lipsticks before choosing a soft metallic sound. I used to find that sort of thing romantic, you know: the total devotion to something ordinary, the love of a good detail. I’m still impressed by the devotion on most days. But today it feels like another example that the reality of women’s existence in the world has been shaped to be seen, never heard; witnessed, but never believed; desired but never trusted. Nowadays I think of how much effort and energy is put into dismissing women — right down to the sound her lipstick may produce — and it makes me want to scream louder than I have words for.

We’re told women have to be respectable, beautiful, but not too beautiful, just enough to be paid attention to, and even then, what we say doesn’t seem to count. I wish I could throw all my lipstick bullets directly at Brett Kavanaugh’s throat and magically have him truly fear women, and respect women, and work for women. But that won’t happen. Barring that possibility, sure, I understand the allure of buying a “F*ck Kavanaugh” lipstick that funds those working against him. I do like the color and I like that my money is being used for … something good.

But disaster capitalism is still the product of a disaster. I don’t want to be a doomed doe like Hepburn’s character, shaking as I glue myself together with some rouge. I find it more useful to practice my throw.