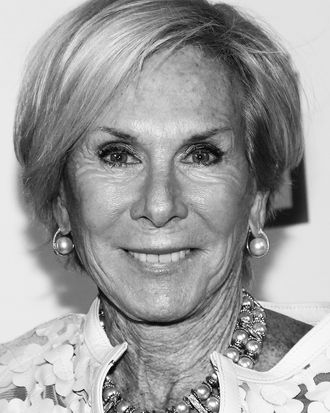

Amanda “Binky” Urban — the ICM agent who represents, among many others, Michael Pollan, Toni Morrison, Haruki Murakami, Walter Isaacson, Mary Karr, Richard Ford, Anthony Doerr, and the estates of E. B. White, Nora Ephron, and E. L. Doctorow — started on the road to becoming the most powerful woman in book publishing thanks to a chance encounter with Mrs. Geffael, formerly of Short Hills, on June 5, 1968. It was the day Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated.

Back then, Binky Urban (it’s a family nickname; that’s all she wants to say about it), 21 and freshly graduated from Wheaton College, wasn’t expected by anyone in her milieu to go to work at all. She’d been raised in affluent Summit, New Jersey, where “we all went to private schools and had princess telephones in our rooms and the dads had big jobs in New York and the mothers stayed home.”

“My dad woke me that morning,” she recalls, “and said, ‘Bobby Kennedy’s been shot.’ I said, ‘I don’t want to sit here and watch television all day. Can you wait while I get dressed and take me’ — on the Erie Lackawanna, the train with the rattan seats — ‘into New York with you?’ I went immediately to the University Club, where I put my stuff in the ladies’ locker room. Then I walked out onto Fifth Avenue, thinking, What am I going to do today?, and literally ran into the mother of one of my best friends from Short Hills. I said, ‘Mrs. Geffael! How are you?’ She’d gotten divorced and said, ‘I’m great! I’m living in New York. I bought a personnel agency.’ She said, ‘Don’t you want a job?’

“I said, ‘I don’t know. Do I want a job?’ She said, ‘Yes, come with me.’ She took me back to her office, and they sent me on an interview to be the secretary to the director of marketing for this company called National Student Marketing Corporation. They offered me a job. It was $100 a week.

“At dinner that night, Dad said, ‘So what happened today?’ I said, ‘I got a job.’ He was like, ‘What? Where? Doing what?’ I told him, and he completely disapproved: ‘If you want a job, you will go to work at Condé Nast.’ Which even then was what … girls … did. So I interviewed to be an assistant to the editor at one of the women’s magazines, and the woman interviewing me made a pass at me! I was so confused by it! I unapplied for that job. I wanted to take my job.

“Then the best thing in life happened to me: My dad just cut me off. I got an apartment I could afford on $100 a week. What I couldn’t actually afford was a sleep sofa.

I called my dad and I said, ‘Can you buy me a sleep sofa?’ He said ‘No, but I can take you to the bank to get a loan to buy a sleep sofa. And then you’ll have a credit rating.’ ”

Urban kept getting jobs: in marketing, for a gubernatorial campaign, and then for Grey Advertising, where at age 25 she helped steer the agency through an EEOC discrimination claim considered a test case for the entire industry. “These white males from Greenwich, Connecticut, who couldn’t stand that they had to have hiring goals and affirmative-action programs, hired me to negotiate with Eleanor Holmes Norton,” she says. She then left to work on the business side at New York, where her mentor was the late Clay Felker, the magazine’s founding editor. It was he who suggested that she become an agent.

Binky Urban: Lynn Nesbit hired me at ICM. While I was building my own list, she gave me a certain amount of spillover, as you do when you’re the rainmaker. One day, she threw a letter on my desk and said, “You might want to follow up.” The letter read, “Dear Ms. Nesbit, I’ve never had an agent before, but I’m thinking now of getting one, and if you’re interested in talking to me, please call me before noon Rocky Mountain time at this phone number. Signed, Cormac McCarthy.”

I’d read Suttree. I don’t think anybody reads Suttree and doesn’t think it’s an amazing book.

So I called him up and said, “I’m not Lynn Nesbit and I’m just starting out. But I’ll work really hard for you.” He said, in his gravelly voice, “Well, that sounds fine to me.” I did some research and realized that none of his books at Random House had ever sold more than 2,500 copies in hardcover. Sonny Mehta, who had published him in the U.K., had just taken over at Alfred A. Knopf. I called him and said, “Do you want to publish Cormac McCarthy? It seems to me that Random House isn’t doing a really great job by him.” Sonny said, “I’d love that.” I called Random House and said, “Is it okay if I move Cormac McCarthy over to Knopf?” and the head of Random House said, “I can’t believe I’m picking up the phone to talk about an author who’s never sold more than 2,500 copies. Of course you can move him over to Knopf.” And the next book was All the Pretty Horses.… It’s such a great story.

Lisa Chase: What was your first big deal?

My first six-figure deal was almost 40 years ago, for two Australian doctors. It was about how, in these remote villages in Africa, women read their vaginal mucus for birth control. When it was stringy, it meant you were at the height of your ovulation. When it got cloudy and lumpy, the moment had passed. Millions of women all over the world had learned how to do this, and then technology and medicine overtook — women forgot how to read their own bodies. I was in my early 30s, and there were women who were having trouble getting pregnant. I called up Jason Epstein, the head of Random House. If you know Jason, the last thing in the world he wanted was to hear was about vaginal mucus. But I pitched him this book, he read it, and he made me an offer of $100,000.

How’d the book do?

It just sold for years.

Is it correct to think of agenting as a female-dominated profession?

Totally. When I started there was a lot of that female nurturing quality attributed to agenting. I had a formative experience with Toni Morrison. When Lynn left ICM to go into partnership with Mort Janklow, Toni invited me to lunch. She said, “I love Lynn. She’s been my agent for a long time. And she’s also become a really good friend. Which means that when we get on the phone, we talk about our boyfriends, our love lives, our kids. I just want somebody who can pay attention to my business. Can you do that?” And I said, “Yes, I can do that.” That was a great life lesson. Because some of my clients are among my best friends, but I always try to be vigilant that I’m in their lives for one big reason: to make them money.

Do you have any hard-and-fast rules?

My big rule is, Don’t lie. I mean, not only do I not lie, but everyone knows I’m pretty, well, what’s the word?

Straightforward?

Straightforward is the nice word for it. I just think there are not enough people telling the truth, delivering bad news fast — not prevaricating or procrastinating.

How do you feel when people say, “Binky Urban is the most powerful literary agent in New York”?

I don’t even know what that means. You know, power is such a male word. Being dominant is not anything I care about. What I care about is being effective, being respected. The only way that could mean power is that I’ve got a lot of great authors. And publishers are maybe less apt to screw around with me than someone starting out. They need to get along with me because I’ve got the talent.

Do you remember a time when you realized they were less apt to mess around with you?

When American Psycho was killed by Simon and Schuster. The head of Gulf & Western, Simon and Schuster’s then–parent company, was just appalled at the book. Dick Snyder, an S&S chairman at the time, called and got me out of lunch to tell me that they were canceling the contract. And that Bret Ellis could keep 100 percent of the advance. The book was literally about to be published! “I won’t go into the gutter if you won’t,” he said, hoping I wouldn’t go to the press with the story.

I finished lunch and went back to the office, thinking the whole time, Well, now, what am I going to do? American Psycho is a satire. It’s a funny book. Everywhere else in the world, people immediately read it for what it was. Only in America did we have problems, do you know? My own boss came in and said to me, “Why are you fooling around with this guy? I mean, no one’s going to care about Bret Ellis in five years.”

I thought, The best thing I can do is place this book with America’s premier publisher, and that was of course Knopf. I called Sonny Mehta and I said, “I don’t care what you pay for this book. But I think it should be published right away because it’s going to get a lot of press. Your imprimatur will help people understand what this is.” He said yes! And published it like a week later. It was really fun pulling that off.

Has there ever been a time when you made a decision and you felt like, “I didn’t use my”—I know you don’t want to use the word power — has there ever been a time when you regret how you used your effectiveness?

Yeah. The Times’ David Carr wanted to write his memoir about his life as a drug addict. He came in and I actually said to him, “David, can you really remember enough of your life to write a memoir? Memoir is really hard to do. I know kind of a lot about it.” And he said, “Okay, fair enough,” and he left me and wrote a huge best seller, The Night of the Gun. I shouldn’t have doubted him. I liked him so much. I should have just said, “Okay, do it.”

Have you ever done the calculation I have X million best-selling books in print?

I don’t even know how I’d do that. However: two Nobels for Literature and two for Peace. Toni Morrison, Kazuo Ishiguro, Malala Yousafzai, and Nadia Murad. Four Nobels. But who’s counting?

*A version of this article appears in the October 15, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!