FORT BERTHOLD, ND — A man on the campaign trail refused to shake North Dakota senator Heidi Heitkamp’s hand because she voted against Brett Kavanaugh, she tells me one afternoon, inside a leather-bound conference room at 4 Bears Casino Lodge on Fort Berthold reservation. “Because, he said, ‘then you’d find me guilty of sexual assault.’” But not all North Dakota voters; not all North Dakota men.

The Kavanaugh vote was why, three days ago, Roger White Owl, a soft-spoken elder of the Hidatsa-proper, gave Heitkamp sage transplanted from the reservation’s original sacred plants. Heitkamp’s no vote, says White Owl, “reminded me of our own people’s warrior society. It’s called the dog soldiers society.” He is 65 and has a slight tremor. “The dog soldiers would stake themselves down to the ground and stand there,” he explains. “They would sacrifice their lives to help and protect the people. She staked herself down and said no to Kavanaugh, knowing full well that she was sacrificing — maybe sacrificing — her career as a senator.”

White Owl isn’t the only one to explain the stakes of that vote to me in life-or-death terms. “She calls it political courage,” says Jim Poolman, a vice-chair of the state GOP. “I might call it political suicide.” It’s been less than three weeks since Heitkamp explained her ultimately futile vote against Kavanaugh by invoking the survivors of violence she had known and worked for, women in Native communities she’d fought to include in the federal Violence Against Women Act. “She may lose,” her brother, a radio-show host, said at the time. “But in the morning, when she’s brushing her teeth, she needs to like the person she sees.” Some of the shine of that moment of principle, though, dulled less than two weeks later, when Heitkamp had to apologize for a newspaper ad listing dozens of women as survivors of abuse — some added without their knowledge or consent.

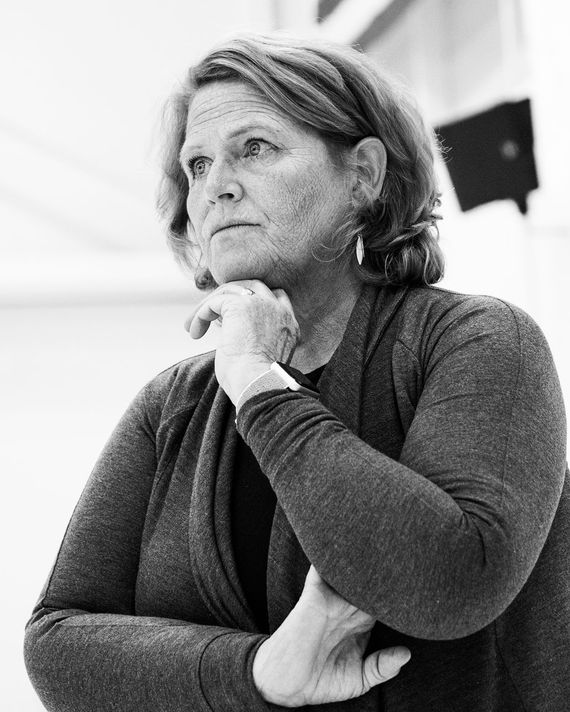

No wonder Heitkamp is tense today, darting across the state in a charter plane to campaign with retired Republican senator Chuck Hagel, anticipating my questions so intently that she begins answering two words in, concerned that I missed the better-attended rally three days ago. She bristles when I ask her if being behind in the polls (the last one has her down nine points) has liberated her to speak her mind. “I am who I am,” she says. “I’m not somebody who pulls my punches one way or another.”

Who she is, in addition to one of the most endangered senators in the country, is a canny, inexhaustible political operator; a policy enthusiast; a woman who seems to come by her you bet folksiness honestly. She is someone people here like. In fact, so many people like Heidi Heitkamp in North Dakota that her opponent, Representative Kevin Cramer, himself says in a television ad, “We all like Heidi.” (There’s a “but.”)

Heitkamp denies that she is significantly down in the polls — she says many of the pollsters trying to survey North Dakota are “incompetent” — though she declines to provide contrary evidence. “The thing that everybody needs to understand is, I need 150,000 votes,” she says. “You can count 150,000 votes. You can motivate 150,000 votes.”

It’s mostly Heitkamp herself that makes people in North Dakota unconvinced that this race is over, even as most of the political class has moved on. (Trump’s handlers left the state off his final-week rally list, though Joe Biden is about to campaign here.) But it’s also voters like White Owl, here in the 4 Bears ballroom, near the slot-machine smoking parlor where seniors from Saskatchewan and Minnesota are pulling levers. If she’s lucky, what look a lot like hurdles — Heitkamp’s vote against Trump’s Supreme Court justice in a state he won by 36 points, the state’s restrictive new voter-ID law — could form the scaffolding of a win.

The stand Heitkamp took on Kavanaugh, whatever else it did, earned her unprecedented millions in donations and the admiration of voters like White Owl. North Dakota’s new requirement that all voters must have a street address — and surely this is a total coincidence — lopsidedly affects the same Native American voters who helped Heitkamp win in 2012 with a margin of less than 3,000 votes. But the law could boomerang on its Republican sponsors, as community organizers, some cool on Heitkamp because of her support for the Dakota Access Pipeline, spring into indignant action. In a state where a 500-vote swing can decide political fates — North Dakota’s, and potentially even the U.S. Senate’s — everything matters, and anything is possible.

But it won’t be easy. So it’s a good time for Heitkamp to meet White Owl and receive the gift of sage. White Owl’s partner Sarah Dea tells me they asked for permission to transplant some scraggly cuttings to their apartment by praying over the original patch and promising never to sell the plants. Who is Heitkamp? Someone who, presented with the bundle of dried sage wrapped in red yarn, starts to cry.

The 4 Bears Casino sits on Lake Sakakawea, a man-made lake, a lake of pain and home to generations of ghosts. In the middle of the last century, the federal government orchestrated a dam project here that evacuated and then flooded entire Indian settlements and wiped out the local economy. Tribal leaders reluctantly made a deal; you can see one of them weeping at the 1948 bill signing. When Mark Fox, chairman of the three affiliated tribes of Fort Berthold, mentions the dam, it’s in the same breath as smallpox. In August, the lake gave up the body of 32-year-old Olivia Lone Bear, a reservation resident who had been missing for nine months.

Not much has been released about the circumstances of Lone Bear’s death, but she lived in a community that had tried to make its peace with North Dakota’s oil boom and subsequently saw an influx of outside workers and a spike in reported sexual assaults. In 2017, when Heitkamp introduced an act named for the brutally murdered Native woman Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, there were 125 reported cases of missing Native women in North Dakota alone, among an estimated population of only 30,000 tribal members statewide — and that’s just what was reported. Nationwide, Native women are ten times more likely to be the victims of domestic abuse, and are much likelier to be victimized by non-Native people. But for decades, the Supreme Court had made it easier for non-Natives to commit crimes on reservations, by ruling in 1978 that tribal authorities couldn’t prosecute them even for crimes on Native soil.

All this mattered to Heitkamp long before that same court’s newest member, Kavanaugh, forced her to pick a side between accusers and accused, and to summon these women’s pain to explain her choice. As North Dakota’s attorney general, she was among those to push for a federal carve out to allow reservations to prosecute non-Indian domestic-violence abusers themselves, rather than wait for state or federal authorities to do so. (One of the people who had urged Heitkamp in the early ’90s to run for attorney general in the first place, she tells me, was a domestic-violence activist. “The previous attorney general had issued murder statistics and said that North Dakota shouldn’t be worried about the homicides,” Heitkamp recalls, “because most of them were domestic-violence situations.”)

When Heitkamp arrived in the Senate in 2013, she co-sponsored the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act that included giving tribes the right to prosecute non-Natives who committed domestic violence on reservations. That provision was not popular with some Republican senators. “Jeff Sessions argued with me,” Heitkamp says. “It’s one of the reasons that I did not vote to confirm Jeff Sessions, because of his position on the Violence Against Women Act and Indian jurisdiction.”

Heitkamp’s now-opponent Kevin Cramer — the same one who this fall wondered if sexual assault really disqualified someone to serve on the Supreme Court — also had his doubts. In 2013, at a theoretically routine meeting with local anti-violence activists, Cramer told advocate and survivor Melissa Merrick, “As a non-Native man, I do not feel secure stepping onto the reservation now.” (He later apologized, saying his “tone and rhetoric” were “better suited for active debate in Congress rather than in addressing the protectors of our most vulnerable citizens.” Cramer ultimately voted for the bill despite his objections to that part of it.)

Now that they have the power to do so, tribal police and prosecutors are proceeding carefully on going after non-Indian abusers on reservations. Shaun Eastman, a tribal attorney on Lake Traverse reservation, still winces when she remembers the non-Indian man who openly beat his wife at a reservation gas station but, because the prosecution power wasn’t yet in effect, could only be arrested for disorderly conduct. (The best tribal police could do at the time, she says, was give the woman a running start.) Since then, eight non-Native people have been convicted there for committing domestic violence against tribe members, and as of last spring, 143 arrests nationwide have led to no constitutional challenges. The last thing the tribal authorities want, Eastman said, is for a bad set of facts to reach the Supreme Court and take down the whole law.

Up there, of course, Brett Kavanaugh would have one of the deciding votes.

Inside the 4 Bears Casino ballroom, Heitkamp holds up a poster board of all of the veterans of her family: her father, uncles on both sides. Native Americans, everyone here knows, are overrepresented in the military. “The only difference between my relatives and your relatives,” Heitkamp says, “is that when yours came home they couldn’t vote.” Her closing is, “You will not be the last, ever, to me. You are the first people and you will be first to me.” She tells an employee who opens the door for us,

“Don’t forget to vote. Because they don’t want you to do it.”

“They” is the Republican-controlled legislature that, not long after Heitkamp’s surprise victory in 2012 on the strength of the Native American vote, passed a law requiring proof of a residential address to vote. Many Native Americans who live on reservations use P.O. boxes to receive their mail instead of street addresses. As a federal district court judge later pointed out, 19 percent of Native American eligible voters in North Dakota don’t have the qualifying ID, a rate twice as high as the general population, and are less likely to have the backup documents the state will accept. Nonetheless, on October 9, the Supreme Court allowed the law to go into effect, over a dissent by Ruth Bader Ginsburg. “The legislature clearly passed a law to make it tougher for Native American people to vote,” says Heitkamp.

Tribal governments and activists are scrambling to find work-arounds, including printing free ID cards on the spot, in time for Election Day. (Over the weekend, Dave Matthews and Mark Ruffalo rolled into reservations to raise awareness.) They also filed a new legal challenge this week. No one knows whether the backlash to the law will juice turnout, but it has already brought back into the fold some of the Native American activists who remember, to name one example, Heitkamp’s 2016 statement calling the Dakota Access Pipeline protesters — a group that included many members of local tribes — “increasingly violent and unlawful.” However angry advocates were at Heitkamp for picking the energy industry and law enforcement over them, they’re livid at the voter-ID law. And they fully grasp that whoever controls the Senate will also help determine the future of the Supreme Court, with its outsize influence on Native American lives.

To Jodi Gillette, a former Obama administration Native Affairs official in Bismarck who is working against the law, it evokes ancient oppressions. “We’re getting the message to sit down and shut up and be a good Indian,” she said. “That, if it’s it’s too hard for your relatives to vote, that’s their fault. A good Indian says, ‘I don’t deserve to be part of this democracy.’ But those days are over.”

Native turnout is one of the wild cards in a state whose demographics are rather different than those of the country at large. “We don’t really have suburbs,” concedes Tim Purdon, a former U.S. attorney close to the campaign. “But there are lots of moderate Republican women here. If their view of politics tracks other moderate Republican women in other parts of the country, some of those folks might vote for Heidi Heitkamp.”

This is also one of the states where the structural biases of Senate representation reach cartoonish scale. According to FiveThirtyEight, this year, a North Dakotan voter is 28 times more powerful than the national average in determining who controls the Senate, far more than any other state. Among the states pivotal to Senate control this year, only Montana is whiter.

There’s also a recreational marijuana initiative of indeterminate impact. “I would not be surprised if it passes,” says Grand Forks Herald columnist Mike Jacobs. “There is a streak of contrariness in North Dakota’s political tradition.” He thinks that contrariness is why abortion has been a relative nonissue for such a conservative state: The sponsors of restrictive bills at the state level were defeated, and in 2014, so was a fetal personhood ballot initiative.

It feels like a million years ago, and it is in Trump time, but as recently as last June, as Trump signed a bank-deregulation bill, Heitkamp was literally at his side, to Cramer’s open fury. After all, Trump had recruited Cramer to run, only to shout-out his opponent months before the election. Heitkamp had, in fact, been publicly playing nice with Trump since just after the 2016 election, when she visited Trump Tower; last spring, she let it slip that Trump had asked her to switch parties, and there was talk of a Cabinet role. He called her a “good woman.”

Back then, Cramer was left to offer theories of Trump’s apparent soft spot for Heitkamp. “I do think there’s a little difference in that she’s a woman,” he told the Washington Post in June. “That’s probably part of it — that she’s a, you know, a female. He doesn’t want to be that aggressive, maybe. I don’t know.” This would be news, of course, to the legions of women subjected to Trump’s misogyny.

It’s easier to understand why Heitkamp would have wanted to play up her willingness to work with Trump. “I think that we’ve always been willing to sit down and have a discussion about how we can find common purpose and agendas,” Heitkamp says cagily. Relations have cooled, not only because the election is in full swing but because the people in the White House she could work with, like former director of legislative affairs Marc Short, former White House counsel Don McGahn, and former economic adviser Gary Cohn, have left. “I don’t know their successors as well,” she says.

Heitkamp is still running as an independent-minded moderate, but no longer tacking so close to Trump. As political blogger Jim Fuglie says, “She’s got two great issues: soybeans rotting in the fields and her opponent trying to take away health care,” both attributable to Trump — the first through his trade war and the second through support for repealing the Affordable Care Act.

“I think the race is in play,” says Jacobs. “There is a chance that Heitkamp can win, and I think that that chance increases with every day that passes.” Fuglie, who is a Democrat but calls Cramer a friend, says, “Heidi wins a local election. If this becomes national, she loses. Kevin is not the most likable person in North Dakota. Heidi is the most likable woman in North Dakota.”

The day after Heitkamp voted no on Kavanaugh, Cramer told the New York Times, referring to his wife, daughters, mother, and mother-in-law: “They cannot understand this movement toward victimization. They are pioneers of the prairie. These are tough people whose grandparents were tough and great-grandparents were tough.”

This was too much for Heitkamp to bear. She told the Times reporter, tears in her eyes, “I want you to put this in there, it did not make my mom less strong that she was a victim. She got stronger and she made us strong.” She said her mother, a former school cook who died last April at the age of 88, was sexually assaulted in her teens, as Christine Blasey Ford testified she had been.

In the casino conference room, Heitkamp tells me she had never talked about her mother before. “I kind of blurted it out because I was angry,” she says. “I called my sister, and everybody has stood with me, saying that mom would want us to push back.” When I ask her how she first learned of her mother’s story, her eyes again fill with tears. “I’m not gonna talk about that,” she says.

In the 17-day period that spanned the Kavanaugh vote and its aftermath, donors sent Heitkamp a brain-splitting $12.5 million dollars — much of it seemingly from people inspired by her bold stance in a red state. It’s almost as much as Heitkamp raised in the entire preceding term. “You can’t spend that much in North Dakota,” insists the GOP’s Poolman. “She might as well hand out $100 bills.” She might also hire more field organizers and canvassers, whose salaries will be paid by people who appreciated even a potentially suicidal and fruitless vote.

But the aftermath of the vote also led to her campaign’s biggest misstep to date. Cramer’s claim that North Dakota women were too tough to be victims inspired an unnamed Heitkamp staffer, no longer with the campaign, to compile signatures for an open letter that ran in several North Dakota newspapers. “As North Dakotans who have experienced this absolute terror firsthand and survived these crimes,” it read, “we are all prairie tough.” Thanks to what Heitkamp euphemistically describes as “a misunderstanding with lists that were advanced to us through social media,” not all of the women listed as signatories had actually agreed to be named, or even identified as survivors.

So far, in addition to a blanket apology, Heitkamp says she’s reached out to four or five of these women. They’re angry, she says stoically. “I apologized and didn’t ask forgiveness, ’cause I don’t know that that’s my job. You know, that’s not something that I can ask for.”

All Heitkamp can do now, in a state where I was told more than once that the majority of voters have personally met her, is do what worked last time, what Jacobs calls “patiently targeting who she needed to talk to. Almost to the individual.” Anyone who will listen to her explanation of how she meant well, how she wants to keep trying to do better. The people on the reservations who have been let down before. The women, even in North Dakota, who are furious at being subject to the jurisdiction of Brett Kavanaugh and his brethren. She will need each and every one of them.