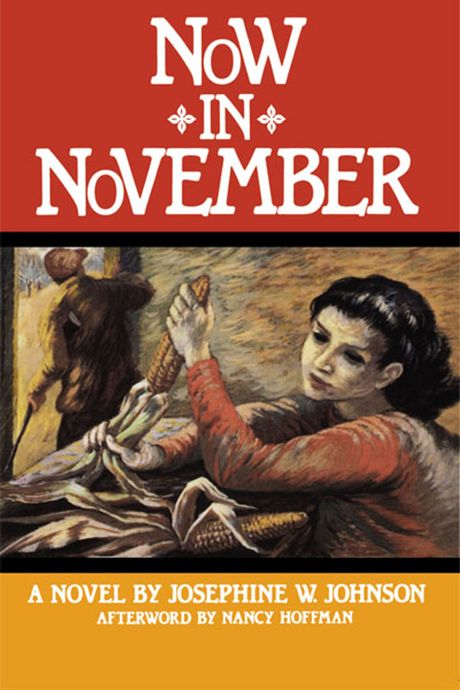

One afternoon in 2013, a women’s history professor introduced me to the youngest-ever recipient of the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, who had been dead for 23 years. “Have you heard of her?” my professor asked, pulling a book off the shelf in her office. “No one’s heard of her.” I hated to admit that I hadn’t either — that Josephine W. Johnson’s Now in November, published in 1934 when Johnson was just 24, was news to me. Ask most readers about American authors from the 1930s and you’ll hear about F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, John Steinbeck, and William Faulkner. Never Josephine W. Johnson. I read the first paragraph of the book right there in the office, and was hooked:

Now in November, I can see our years as a whole. This autumn is like both an end and a beginning to our lives, and those days which seemed confused with the blur of all things too near and familiar are clear and strange now.

Set in the Midwest, the novel is narrated, years after the events described, by Marget, the middle child in the Haldmarne family. The novel is a gorgeous, painful rendering of a family living through the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, but it’s also a study in voice and craft. The narrator is not necessarily the main character, though her deep empathy shapes the story. Marget carefully examines social structures around motherhood and masculinity while also working to understand individuals at their core; so, clearly, does Johnson.

Once I began Now in November, I couldn’t look away from the fiction or the author’s life. Five years later, I still think often about Johnson’s words, about her life’s trajectory, about her unfortunate obscurity. She’s like an old flame: I shoehorn her awkwardly into conversations at parties, asking people if they know her and reminiscing about our college romance.

Josephine Winslow Johnson knew a lot about Marget’s world. She was born in 1910 in Kirkwood, Missouri, to Quaker parents whose families had been settled in the Midwest for several generations. Her youth was dominated by women — three sisters and five aunts. Johnson’s father was, by her account, distant and gruff, though at least one photograph survives of him looking fondly at a young Josephine riding a horse much too big for her. In her alternatingly abstract and precise Seven Houses: a Memoir of Time and Places (1973), Johnson portrays a mostly happy childhood: she was nurtured, educated, loved, and surrounded by books.

She started writing poetry at the precocious age of 7. One of those poems, which she agreed to publish in the Kirkwood Historical Review in 1968, was written when she was 10:

Gravity

I should like very much to see

That queer thing they call gravity

It pulls you to the ground

Without a single sound.

Though not exactly proof of incipient genius, the verse is still a startlingly early example of her commitment to writing (and publishing). In her late teens, she began to publish both poetry and short stories in local magazines like the St. Louis Dispatch, before gaining national attention with work in the Iowa Review, The Atlantic and Harper’s. (I was overjoyed to find some 50 of her stories and articles archived in PDF format on a site that didn’t exist when I’d first heard of her.) In a move rare enough to make headlines today, an editor at Simon & Schuster contacted Johnson directly to ask whether she was working on something longer. Even though publishers used to be far more active in pursuit of new talent, it’s still remarkable that one reached out to a St. Louis University dropout from a small town. This was, after all, the Great Depression. Funds were tight everywhere.

Johnson was indeed working on something longer. Set up in the attic of her mother’s house, she produced the quietly stirring Now in November, which turned out to be a pretty good bet for S&S — winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1935 (then categorized as the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel), when Johnson was only 24. In the eight decades since, no novelist that young has ever won again. Also notable: While Johnson was the ninth woman to win the then relatively young prize, only 20 women have won the prize since.

What happened to Johnson next is, to this day, fairly common. Following a collection of new and previously published stories, Simon & Schuster released her next novel, Jordanstown, in 1937 (when she was just 26), and it flopped. It was an ambitious book with a large cast of characters, many of them fighting for civil rights and justice for farm workers. The New York Times deemed it pat, polemical, and faddish, declaring: “Miss Johnson is undoubtedly a gifted writer, but she will have to do better than ‘Jordanstown’ to win another Pulitzer Prize.” (The Times Book Review was kinder.)

While Jordanstown isn’t as well written as her stories or her debut, its real downfall may have been the socialist politics found within — the underlying message that community could foment a kind of revolution. It’s full of strikes, crusading journalists, worryingly “Red” rowdiness. And it sold abysmally.

Johnson was subsequently dropped by her publisher, though not before submitting another novel. Only 24 pages of it survive, tucked away in the archives of Washington University in St. Louis. The working theory among the handful of scholars who cared enough about Johnson to dig into these papers is that Simon & Schuster really rejected it because it was far too sympathetic to Communism. While Ernest Hemingway could get away with lionizing the Spanish Communists and their swashbuckling allies in For Whom the Bell Tolls, a woman depicting grassroots activism at home could not.

When it came to that activism, Johnson walked the walk. Her work was locally focused, community-based: she and another forgotten author, Fanny Cook, helped establish a school in Copperville, a neighborhood in St. Louis where primarily African-American sharecroppers lived and worked for little pay and had nowhere to formally educate their children. In 1936, Johnson was arrested in Arkansas for encouraging a strike in the cotton fields. Later in her life, she would become an environmentalist and anti-war activist.

Johnson kept writing, of course, and also got married, had three children, and taught for a while at the University of Iowa. Her third published novel was political in an entirely different way. Whether contemporary reviewers realized it or not, Wildwood (1945) was something of a feminist book, or at least an effective critique of the social constraints placed on women’s bodies and sexuality — the punishment they suffered for acting on their desires. But its strange tone, a mix of Gothic and modernist, feels even less palatable to a general reader than Jordanstown.

The Dark Traveler, which came out 16 years later, in 1963, was clearly written in search of a broader audience — at least in its opening pages. It starts out sweet and loving, but turns rather disturbingly, wonderfully dark, delving again into social issues but in a more personal key. The protagonist is Paul, a schizophrenic man with an abusive father and a self-loathing alter ego. When Paul’s uncle takes him in, he tries to find his place in the happy farming family he wishes so much to be a real part of. Here Johnson explicitly addresses something that appears in almost everything she wrote: mental illness. Now in November’s Kerrin suffers symptoms we might file today under labels like eating disorders, depression, and gender dysphoria (which is still, alas, in the DSM-5). Wildwood explores a character’s intense shyness and anxiety, which might now be pathologized as mental illness. And in The Dark Traveler, Johnson critiques institutionalization and instead poses social support as a superior alternative.

Johnson briefly found success again in her late 50s. The Inland Island was a book of essays about the land she lived on in Ohio, subtly advancing her newest cause: environmentalism. In the politically momentous year it was published, 1969, she made the pages of the New York Times again, writing a presciently dire op-ed that referenced Rachel Carson’s classic: “After the first silent spring will come a short and suffocating summer, then asphalt autumn, and in the end, winter. Cold, clean, orderly, concrete winter. Winter forever. And then we will have nothing to fear anymore, nothing to be protected from, nothing to be protected for, nothing at all, in fact, that we or anyone else will want to call our own.”

She never published fiction again.

In 1990, the Times ran an obituary. Readers perusing the page may have paused for a moment on Josephine W. Johnson’s name before moving on, perhaps finding it vaguely familiar. She had been out of the public eye for years, and there was seemingly little cause for people to know who she was.

While Johnson may have been an inconsistent novelist, she’s nevertheless a sadly neglected one. When her writing works, it soars, and even when it doesn’t, her bold ideas and experiments in style and voice are fascinating. The issues explored in her novels are still relevant, and they resonate all the more when viewed through the lens of historical context.

She was an advocate for equality, environmental causes, and an end to pointless, violent wars. And she was an artist who perhaps succeeded too early, forcing her to compete forever with her younger self. First Johnson was a star, then a has-been, and finally a passing notice in the obits. Her books all went out of print until, in 1991, a year after her death, The Feminist Press reissued Now in November. More than a quarter century later, it remains the only one of her books in print, though her others are available second-hand.

Johnson wasn’t ahead of her time, exactly — questions of gender, justice, and mental illness are as old as our attempts to understand such concepts — but she was certainly writing into subjects her contemporaries weren’t willing to seriously take on. Perhaps now we’re finally ready for her.