The nice things about a health and/or science and/or psychology book, if you get a good one, is that it feels like self-help you don’t need to be embarrassed about. (Why self-help feels inherently embarrassing is another matter.) Most of them isolate one thing about yourself or the world that is maybe not as well understood as it should be: dreams, or shame, or psychedelic drugs. By the end, you usually appreciate the subject more, or at least you notice it more, and sometimes, this appreciation/attention combo really does improve your life. If anticipating the start of 2019 has you in self-improvement mode, consider the following books from 2018.

In what I’d call a half memoir, half gonzo journalist–style study on one of the fastest growing industries in the world, author Brigid Delaney explores (and personally tests) a number of highly dubious wellness trends — including an alarming, visceral account of a 101-day “fast” which essentially amounts to self-imposed starvation. Delaney is a little more credulous than I want her to be, but I also think that’s what makes her sympathetic and fun to read. You want her to succeed and be happy. You want that for yourself. The wellness industry knows it, and they’re taking advantage, and this is funny, engaging of one woman’s journey through wellness hell and back. —Katie Heaney

I sort of think this could be a good chaser to Wellmania’s shot, or maybe vice versa, depending on how angry or sympathetic you want to be when you’re done. Here Barbara Ehrenreich rips into the wellness industry with caustic wit and more than a few scientific studies to support her cause. Ehrenreich is more focused on those tools and “remedies” meant to stall (or even, as often advertised, cure) death, a topic of particular interest to her as a person who is at a “reasonable age” at which to die. That sounds dark, and it is, but I also found it really soothing, too. There is really only so much we can do to keep ourselves healthy — and, Ehrenreich argues, a point at which we do more harm than good. —KH

What, exactly, are you worried about when you’re worried about what other people might think of you? I thought about this while reading Hendriksen’s book, and could only come up with this: They’ll know. Who will know … what, exactly? Don’t ask me. But I do think you should ask Hendriksen, who is a clinical psychologist and writes that she has struggled with social anxiety for most of her life. She knows what she’s talking about, in other words, and I love the clearcut phrase she introduces for this vague and swirling feeling of mine: She calls it The Reveal.

Social anxiety, Hendriksen writes, “is about concealment. It’s less about fear and more about shame, a word that can be traced to the Indo-European root skam, meaning ‘to cover.’ In short, shame makes us want to hide.” The book has lots of practical tips, but it was this insight that stayed with me long after reading, in part because understanding the feeling when you’re feeling it can help you handle it, or at least Hendriksen believes it can. “Watch your body for signals,” she writes. “Just as sadness is heavy and fatiguing and anger is tense and agitating, social anxiety feels like an urge to seek cover.” If you learn to catch the feeling in time, you might not have to listen to it. —Melissa Dahl

Speaking of “The Reveal”: I worry a little that I am revealing too much of myself by choosing two books that center on shame as my favorites this year. But Burgo would argue that my hesitation to talk about how much I enjoy talking about shame is likely because we have misunderstood shame in recent years In the late 1980s, psychologist John Bradshaw introduced the concept of “toxic shame,” the “destructive messaging inflicted by parents, educators, and other significant adults in a child’s life that leaves the youth with a sense of being defective and unworthy of love.” (If you’ve ever read a Brene Brown book, this will sound familiar.)

Toxic shame is indeed one kind of shame, but it isn’t the only kind. Burgo believes — and convinced me in the end, too — that a healthy sense of shame is the foundation of self-esteem. Shame helps us see ourselves as we really are; it also helps us see who we could be. As the author phrases it, “I believe that a shame experience sometimes contains an important lesson about who we are or the person we’d like to become; if we dismiss it or resist it, we lose an opportunity to grow.” —MD

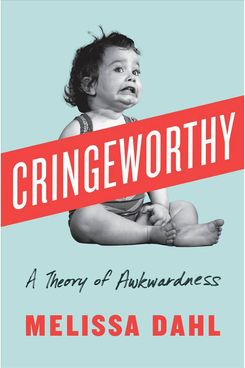

The best science/psychology book I read this year was my editor Melissa Dahl’s: Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness. It’s maybe awkward to say so in this piece that she will be editing, but it’s also true, and maybe the awkwardness is appropriate. In any case, I read it while interviewing for this job, and it made me want to work with her. I particularly appreciate her thoughts on uncertainty: “You could spend your time and energy trying to avoid uncertainty in social or work situations,” she writes, “but I’ve started to think that in certain contexts, you could use it, maybe even transforming the awkwardness into a superpower.” I don’t think I’ve transformed anything into a superpower (yet?), but the idea of examining the deep reasons we instinctively avoid things has stuck with me. —Edith Zimmerman

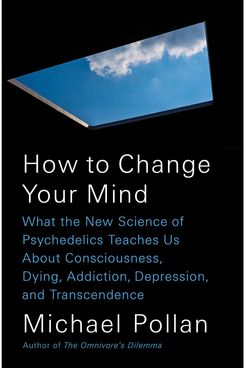

Technically I haven’t finished Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (I’m still trying to make it through the title), but I liked his description of being “on” psychedelic mushrooms — particularly when he said he saw his grandfather’s face in the mirror. (I also liked Eugenia Bone’s chapter on the same topic, in her Mycophilia: Revelations From the Weird World of Mushrooms, from 2013.) I’m glad Pollan’s pushing forward the idea of therapeutic psilocybin use. I don’t enjoy smoking pot, so I was surprised by my own mushroom experience, if I can say that. It gave me a way of thinking about things that I wouldn’t have come to on my own. —EZ

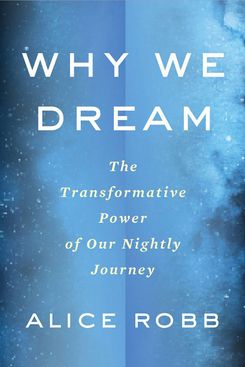

Alice Robb’s Why We Dream: The Transformative Power of Our Nightly Journey was for me a gentle and affecting invitation to reconsider a seemingly boring daily routine. (Imagine if a drug promised to knock you out for eight hours while summoning wild and completely unpredictable hallucinations? Every day??) I especially like the idea of thinking of sleep as a “nightly journey” — not exactly a vacation, but something private to dive into. Almost like a grown-up version of In the Night Kitchen. This is maybe silly, but when I remember to think of it, the “nightly journey” idea makes getting into bed feel like preparing for an adventure. Robb’s encouragement to think of dreams as rehearsals for waking hopes and fears has also been especially eye-opening. But not literally. —EZ

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.