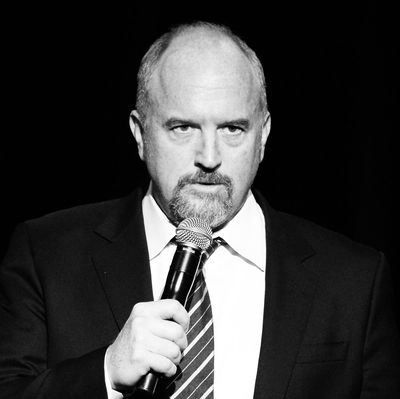

A year ago, as the wave of the #MeToo movement was cresting, Louis C.K. apologized for the incidents of sexual misconduct that had been rumored for years and that, following a New York Times investigation, he’d finally owned up to, writing: “I have spent my long and lucky career talking and saying anything I want. I will now step back and take a long time to listen.” As a longtime C.K. fan who was sickened by the allegations against him but still found value in his body of work, and particularly the way he was able to examine his own bad behavior with a critical eye, I held out hope that he would find some way to redeem himself. His apology seemed, compared to so many of the others, somewhat genuine. Even in a year with myriad indignities — the Kavanaugh confirmation hearing, the layers of accumulated rot at CBS and countless other institutions — I naïvely hoped that at least one of these men might be willing to listen and change.

Well, 2018 is ending, and right on cue, Louis C.K. is back on stage, after taking a “long time” to “listen.” Not to listen to the women he hurt, of course, but to the angry little voice inside of him, that furious, tiny masturbator on his shoulder, whispering in his ear: Aren’t you, Louis C.K., really the biggest victim in all of this? While little snippets of his comeback sets, which began in August, have been shared on social media, last night nearly an hour of audio from a December 16 set leaked, and we finally learned the full measure of what a newly “back” Louis looks like: a man who bitterly criticizes people’s preferred pronouns and derides the Parkland-shooting activists as boring. As comedian Dan Telfer tweeted: “All it took for Louis C.K. to go from ‘fuck Trump’ to sounding exactly like him was being caught.”

In this performance at a club in Long Island, C.K. spent significant time criticizing “kids these days,” whose out-of-control wokeness he appears to blame for his own downfall, instead of blaming himself. Kids such as school-shooting survivors:

You’re not interesting because you went to a high school where kids got shot. Why does that mean I have to listen to you? How does that make you interesting. You didn’t get shot. You pushed some fat kid in the way. Now I gotta listen to you talking?

And kids who use gender-neutral pronouns:

They tell you what to call them. “You should address me as they them because I identify as gender neutral. You should address me as there because I identify as a location and the location is your mother’s cunt.”

In his comedy, C.K. had long depicted himself as an ally, one of the good guys. As Glamour wrote last November in an article about “fake male feminists,” the allegations against C.K. were particularly hurtful because he had “worked overtime to gain the trust of female fans. Today, it’s not just the overtly sexist men that women in entertainment have to fear. Even the ‘good guys’ are using different means to the same end.” It was the fundamental premise that he was a decent guy that enabled C.K. to plumb the dark depths of his psyche for laughs — because they were just thoughts, after all. He seemed to evince a degree of self-awareness that other men lacked. In a famous joke of his, he asked, “How do women still go out with guys, when you consider the fact that there is no greater threat to women than men? We’re the number one threat!” Even though all his actions proved otherwise, I was hoping that some part of this version of Louis — the Louis who seemed to recognize the malignancy of patriarchy and his own complicity in it — might be the one steering the comeback.

A few months ago, Nell Scovell wrote a piece for Vanity Fair called “Here’s What Louis C.K. Should Say In His Next Stand-Up Set.” She put forth a brilliant, imagined set where C.K. takes full responsibility for his actions, delving into his own psyche and engaging deeply with his audience. (“Look, no one wants to admit they’re a horrible person,” she wrote, as C.K. “We’re all the heroes of our own stories. But not in this case. The guy holding his dick is really the guy holding his dick.”) I think the reason feminists like Scovell and myself expended this kind of energy on C.K. is, again, because for so long he seemed like one of the men who “got it” (Scovell said she used to think some of his rape jokes were “modeling consent”), when really he’s actually just one of the men who got away with it. Some part of me has been secretly waiting for his big reckoning, the big introspection, to come. But what in C.K.’s character would make me think that was possible? After all, Scovell wrote that imagined set, not Louis. I’ve been projecting onto him the comic I want him to be, not the comic — and person — he is.

Even after a year of so-called reckoning, there is clearly an audience clamoring for comics to deride PC culture and the “excesses” of #MeToo, and what C.K.’s set shows is how ready he was to take the path of least resistance. It’s so much easier to be prideful and bitter, and cater to that audience than to try and actually become a better, smarter, more empathetic comic. Take Aziz Ansari. Ansari had also long built a brand as a feminist ally; since a story of sexual misconduct went public, he has rebounded with a set The New Yorker calls “a cry against extreme wokeness.” His new material reeks with bitterness. After Jamie Kilstein, formerly a self-identified feminist, was accused of abusive behavior, he rebranded by going on Joe Rogan’s podcast and calling himself “an ex–male feminist.” Meanwhile, Jerry Seinfeld has said he won’t play colleges anymore because college kids are too sensitive.

This past year has shown us that if any profound moments of insight are going to arise from #MeToo, they won’t be coming from the perpetrators. Instead, we’ve seen a crop of ingenious new comedians, many of them women and queer people and people of color — Ali Wong, Hannah Gadsby, Hasan Minhaj — developing a comedy that isn’t based on punching down or enforcing a racist, homophobic, patriarchal status quo. “When Obama was president, reactionary stuff was so much easier to laugh at, because we were making progress as a nation. Now it seems more symptomatic,” Scovell tells me. “Seinfeld saying he’s not going to play colleges anymore; that’s not someone who wants to dig deep and figure out how to reach a new generation. I don’t know what happens to these guys, maybe they get so rich, maybe they’re just so used to hanging out with each other that they just live in this bubble, and it’s too scary outside the bubble. But the whole point of comedy is you’ve gotta find the edges, and you can’t find the edge when you’re in the bubble.”

Or as director and comedian Judd Apatow wrote on Twitter in a long tweet thread about C.K.’s set, “This hacky, unfunny, shallow routine is just a symptom of how people are afraid to feel empathy. It’s much easier to laugh at our most vulnerable than to look at their pain directly & show them love and concern. Louis C.K. is all fear and bitterness now. He can’t look inward.” The reason C.K.’s terrible set hurts so much is because some of us saw in C.K. the false promise of someone who could evolve. “Remember, we are interested because we wonder if down deep he has learned anything this past year,” he continued.

It takes immense resolve to confront one’s flaws, own up to mistakes, and chart an active path toward self-improvement. We live in a world where being a reactionary asshole is as lucrative, if not more lucrative, than being a good guy. C.K. could have changed, but that would have been difficult and terrifying; he clearly decided it wasn’t worth it and he could make money by giving into his worst impulses instead. Why are we looking to men like C.K. at all? What did we expect? After all, as Scovell says: “Most of these guys just aren’t that smart or that deep.”